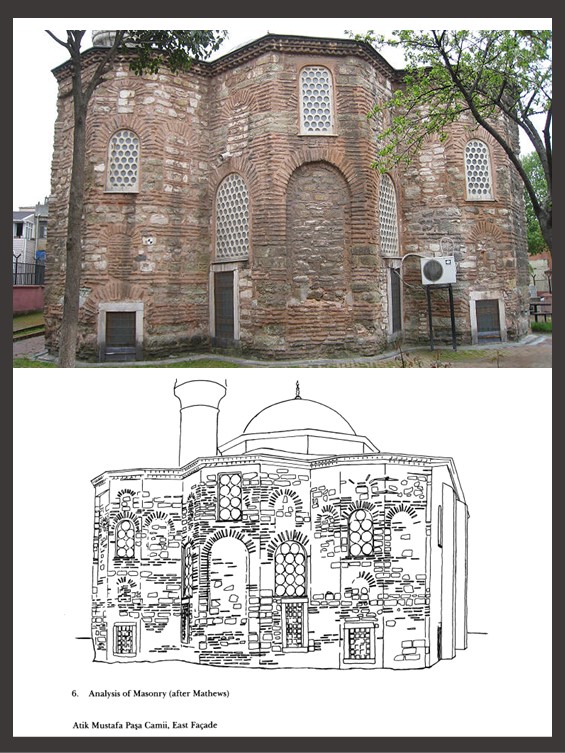

Photograph by Dick Osseman, East Façade, https://pbase.com/dosseman/atikmustafa

East Façade, Analysis of Masonry (after Mathews) https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291520?seq=8#metadata_info_tab_contents

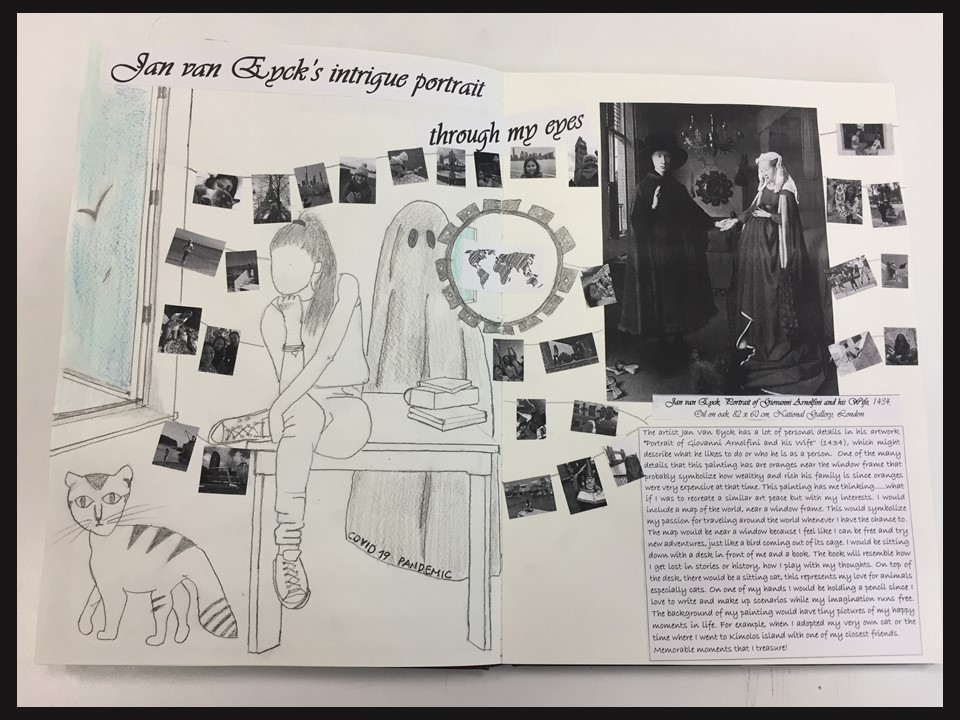

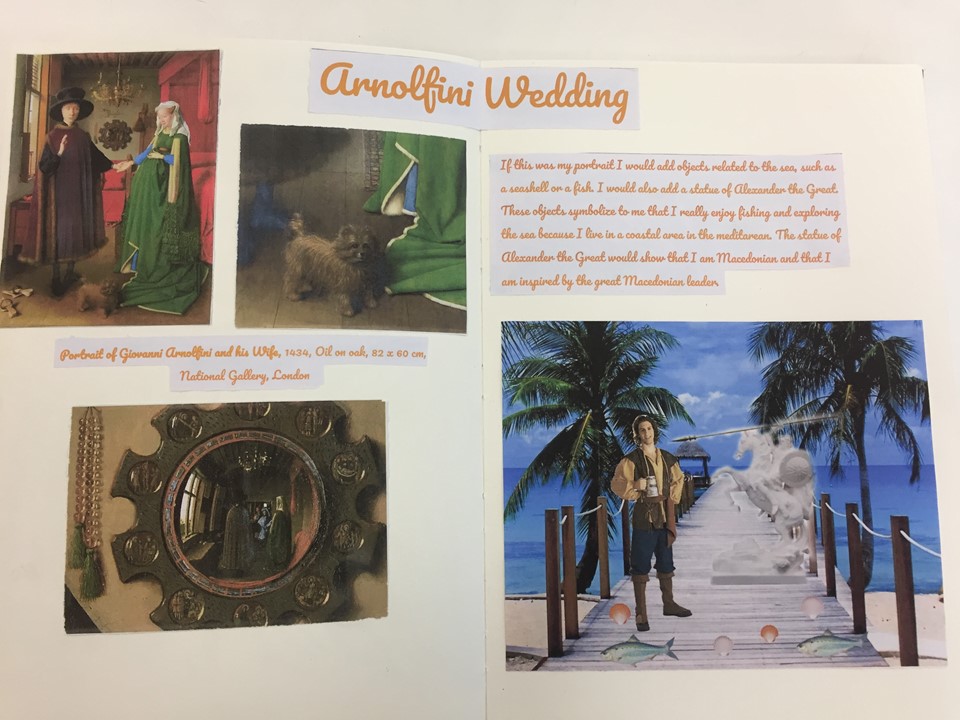

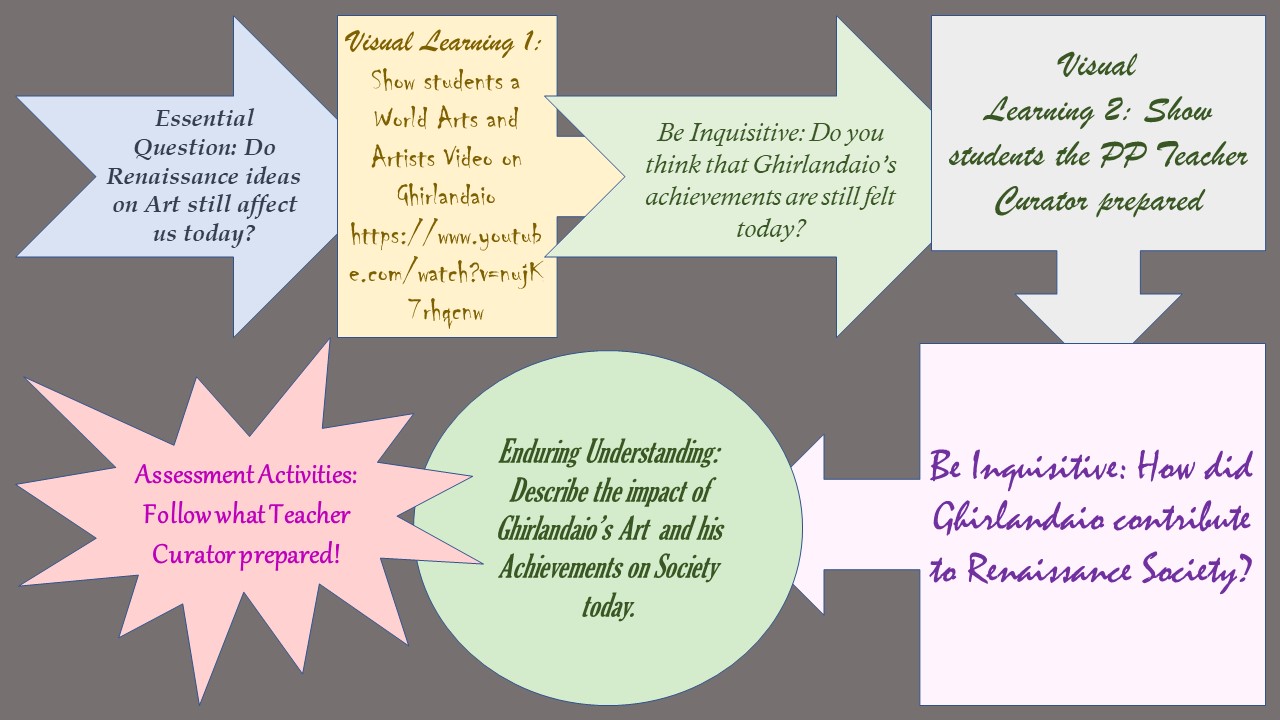

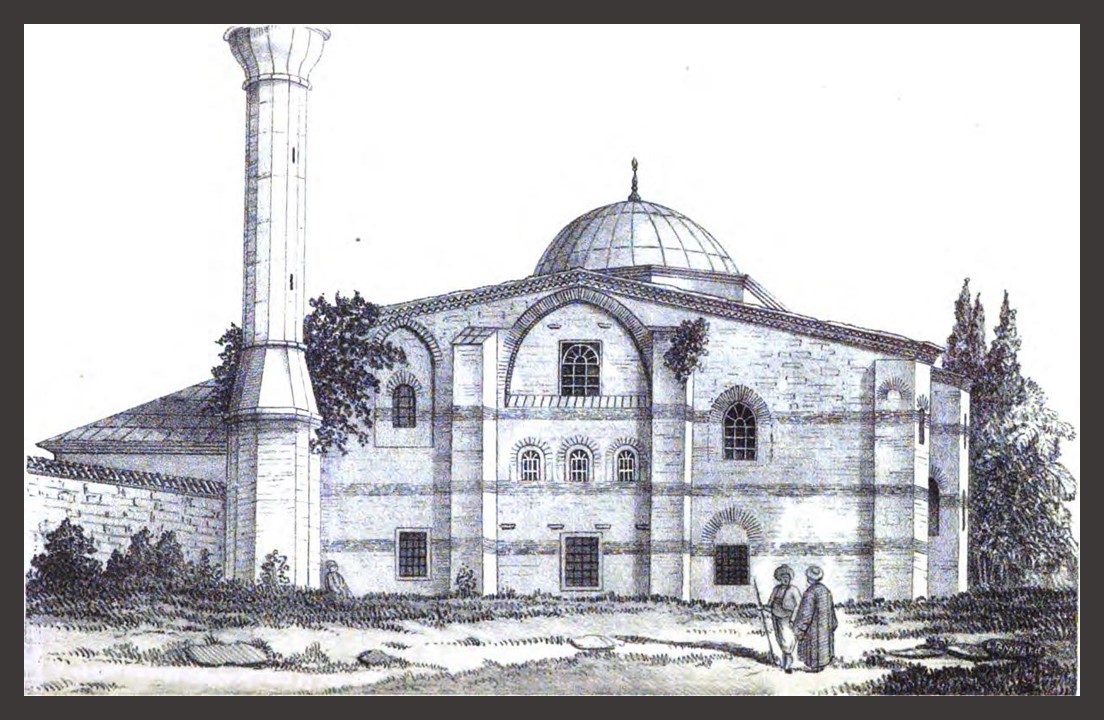

It’s bitter cold, a snowy Sunday in the συμβασιλεύουσα του Βυζαντίου and I enjoy reading “Notes on the Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii in Istanbul and its frescoes” by Thomas F. Mathews and Ernest J. W. Hawkins in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 39 (1985), pp. 125-134. My goal is to prepare for a new POST, titled… Unidentified Byzantine Church in Constantinople known today as Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291520?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Photograph by Dick Osseman https://pbase.com/dosseman/atikmustafa

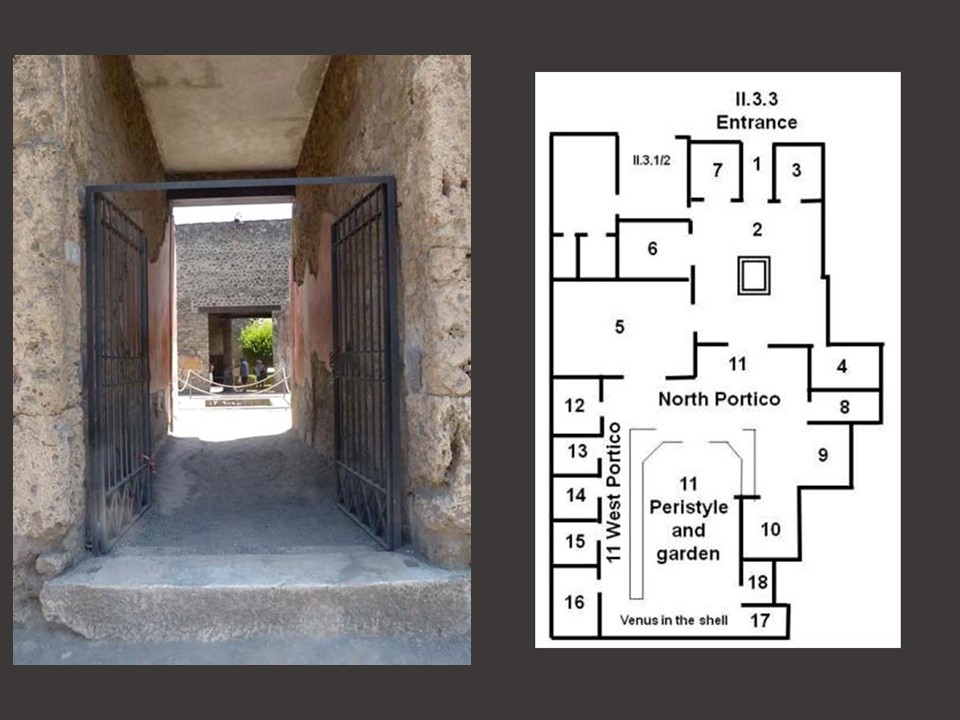

Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii is a historic Byzantine church in Constantinople, an Ottoman Mosque of great importance for the Muslims, and an intriguing building for the expert Art Historians in the academic world. I have to confess I never visited the building and that makes it difficult to talk about it… I rely, however, on Mathews and Hawkins Dumbarton Oaks Paper, the Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World presentation, the Byzantine Legacy report, and the precious photographs taken by Dick Ossemann. This may not be “all-inclusive,” it is the groundwork for my next trip… στην Πόλη! https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291520?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents, http://constantinople.ehw.gr/forms/fLemmaBodyExtended.aspx?lemmaID=11785, https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/atik and https://pbase.com/dosseman/atikmustafa

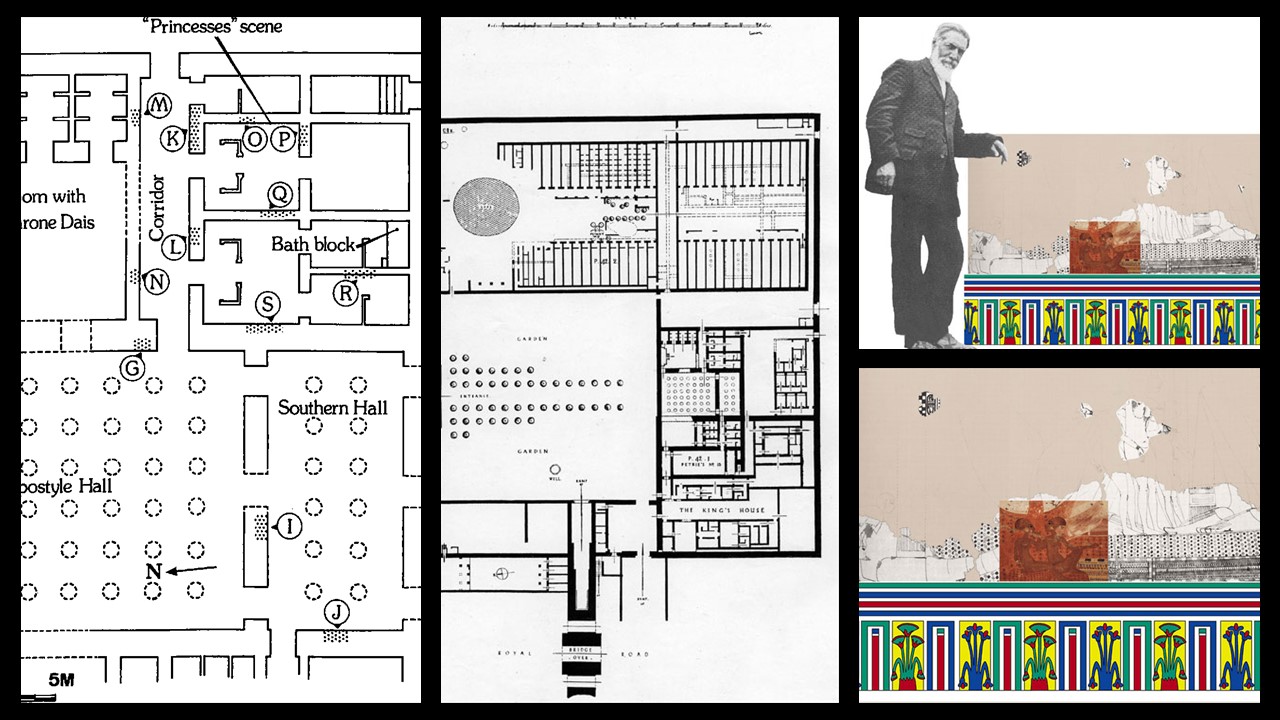

References to early 20th-century bibliography and logical deductions lead Mathews and Hawkins to a first acceptance that the Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii is “the earliest Constantinopolitan example of a cross-domed church (and indeed the first Constantinopolitan church after Iconoclasm).” The authors further studied the articulation of the East End of the building, the design of the Apses (p. 127), the windows in the apses, drew comparisons to many Constantinopolitan churches for plausible similarities and drew the conclusion that the Atik share the most similarities with “the Theotokos of Lips (church) of 907 and the Myrelaion 920-22. With these churches the Atik shares the basic plan of three triple-faceted apses in which surfaces begin to be broken up by windows and niches set at varying levels.” Further comparisons (pp.127-128) on where apse windows were placed and the lack of horizontal cornices enhanced the belief that Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii “while closely related to the Lips and the Myrelaion, seems to represent an earlier stage in the evolution of apse design. Very likely it belongs to the second half of the ninth century in the new surge of church building known from literary sources to have followed the defeat of Iconoclasm in 842 and the accession of Basil I in 867.” https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291520?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents

The Dumbarton Oaks Paper by Mathews and Hawkins is an inexhaustible source of information I enjoyed reading. Groundwork accomplished, I feel ready for a future trip… στην Πόλη!

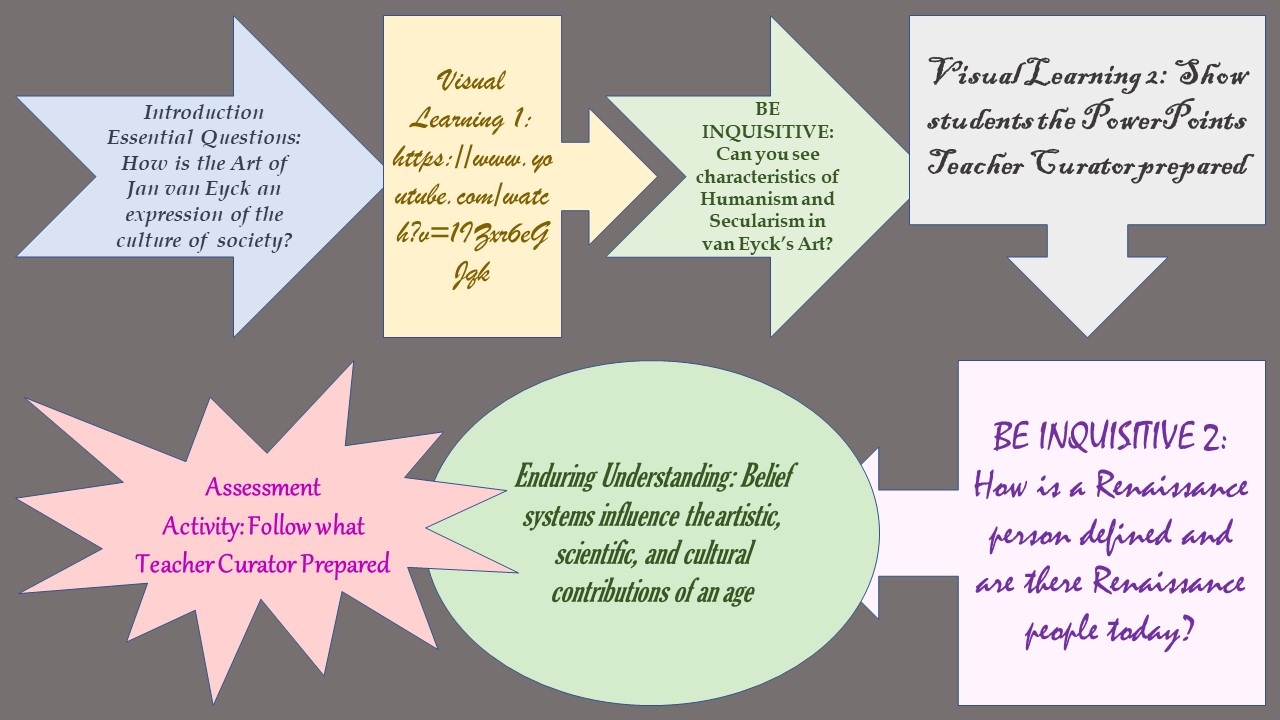

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

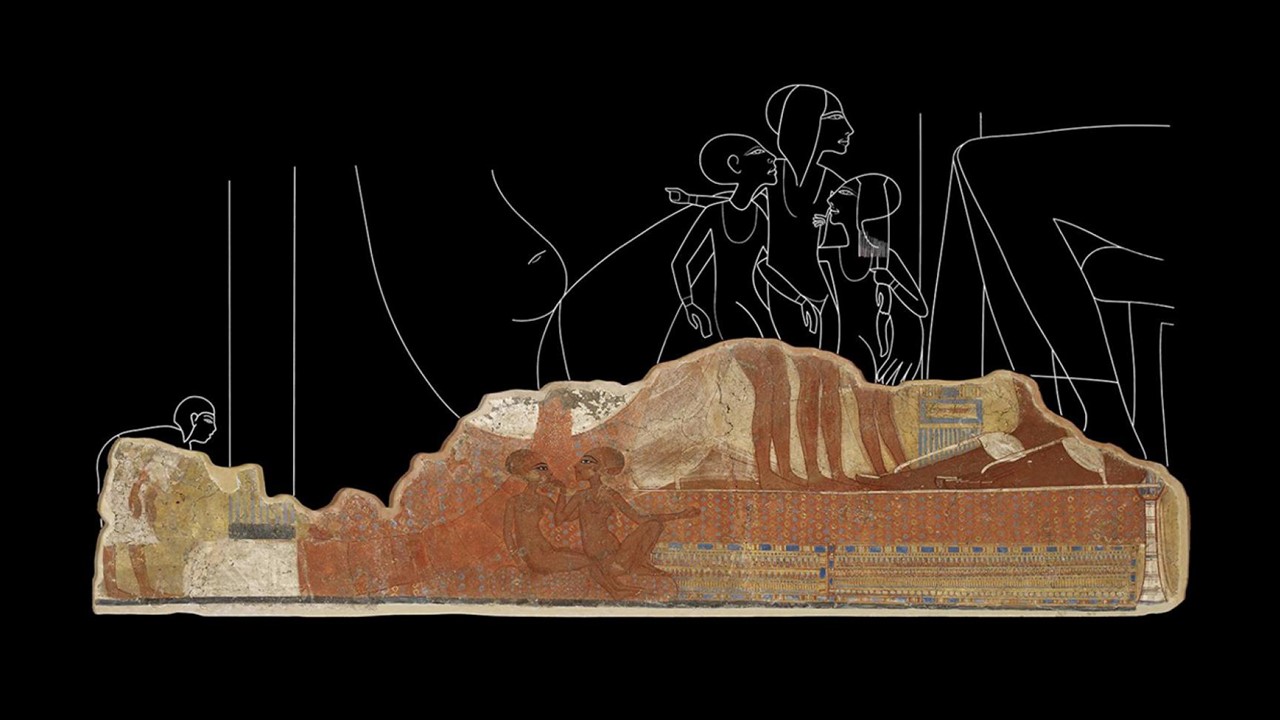

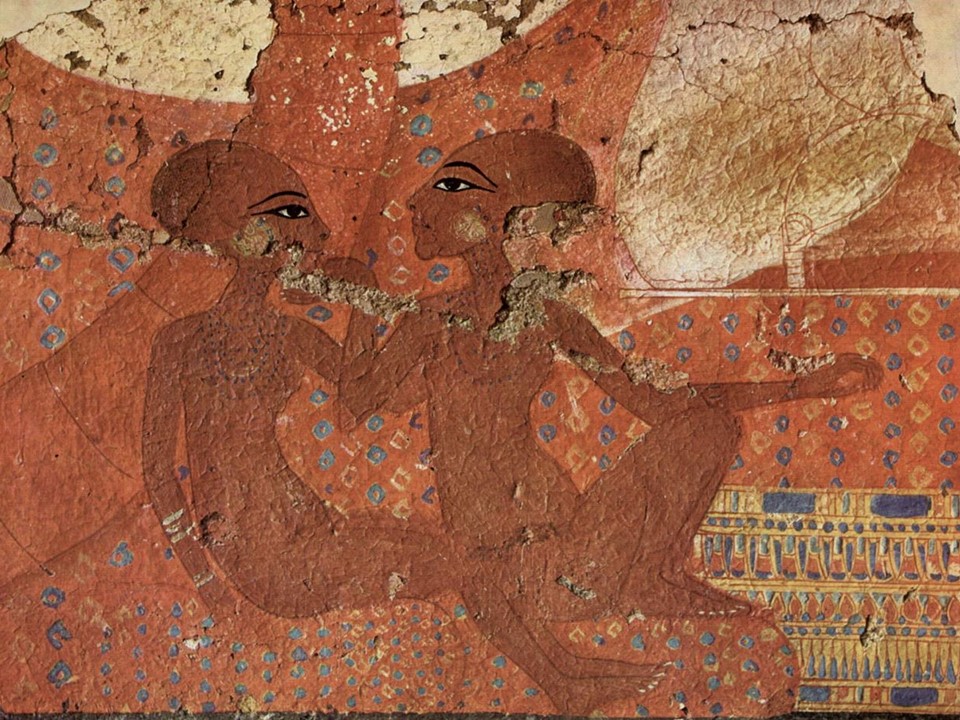

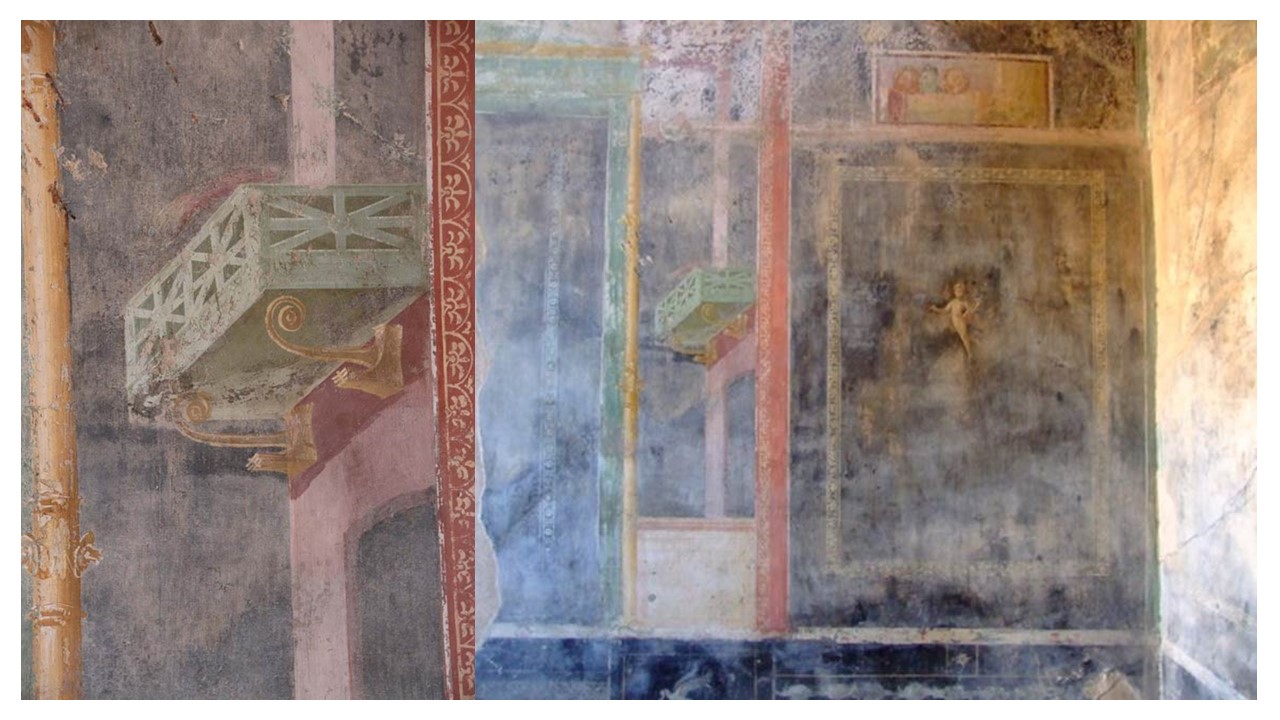

South Wall Frescoes, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291520?seq=8#metadata_info_tab_contents