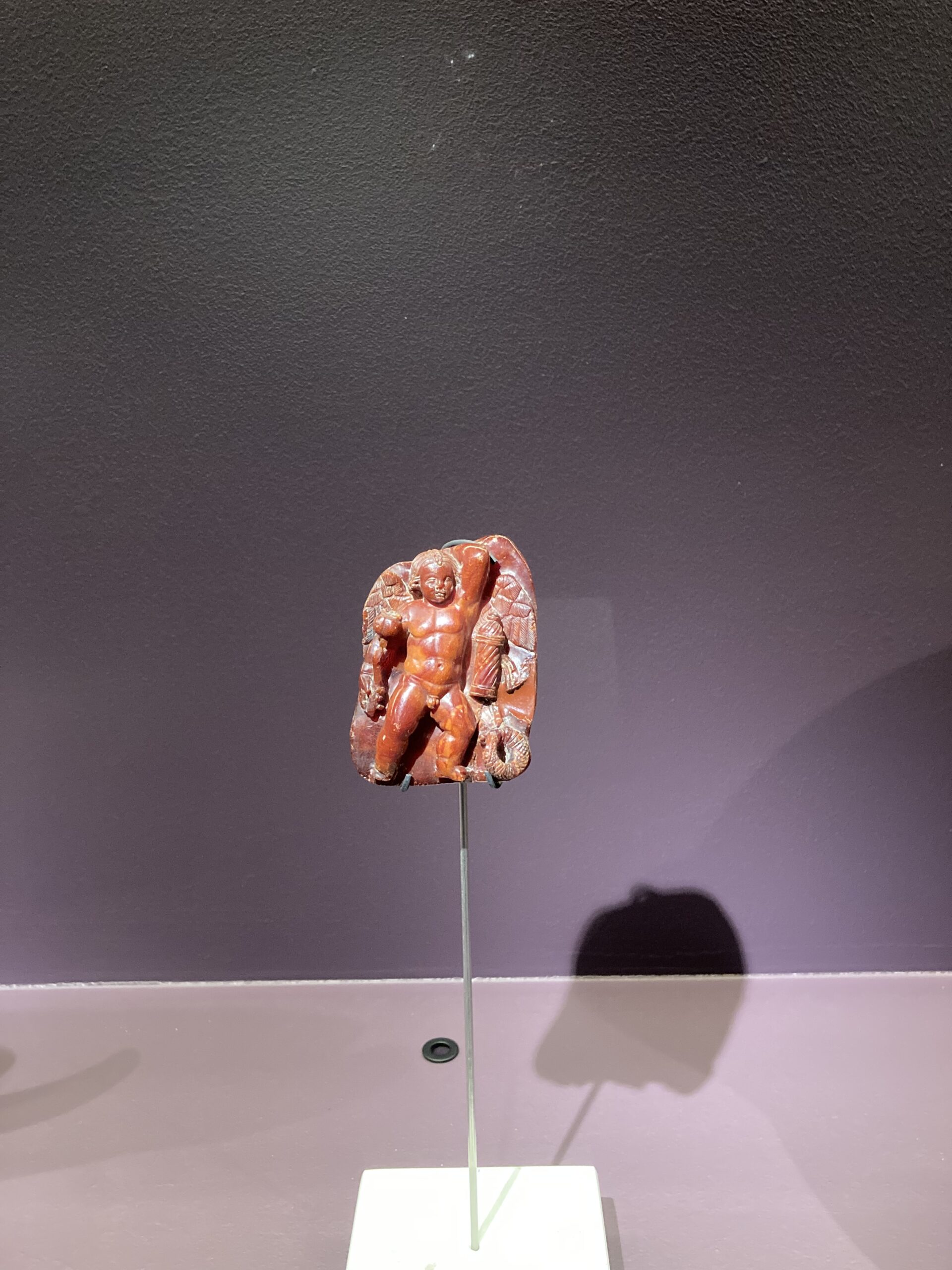

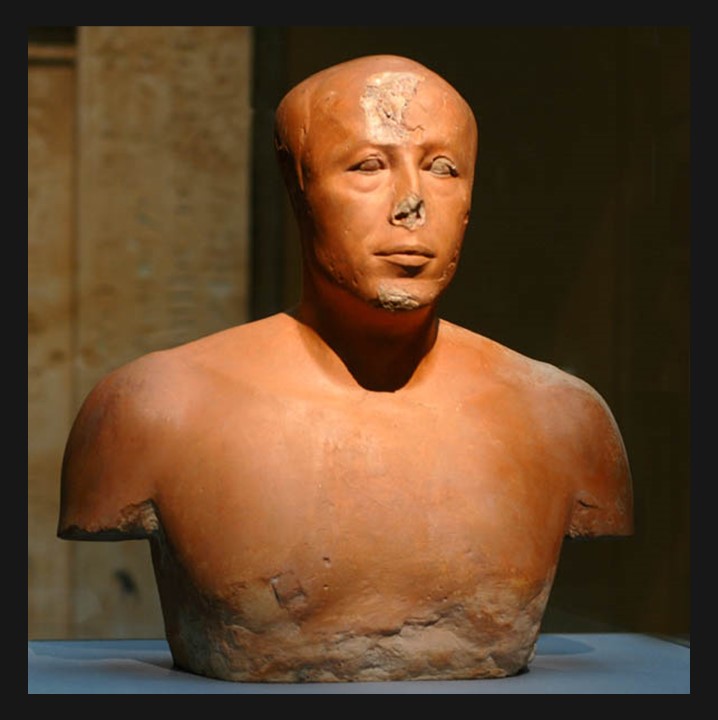

In the world of ancient Egyptian art, true portraits were a rarity, making the Bust of Prince Ankhhaf a remarkable exception. Housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, this limestone bust, coated with a delicate layer of plaster, showcases the masterful hand that sculpted its intricate details. Unlike the stylized depictions typical of the era, Ankhhaf’s visage is that of a real individual, imbued with personality and character. Historical inscriptions from his tomb reveal Ankhhaf’s royal lineage as the son of King Sneferu, brother to Pharaoh Khufu, and a high-ranking official who served as vizier and overseer of works for his nephew, Pharaoh Khafre. In these roles, Ankhhaf may have played a pivotal part in overseeing the construction of the second pyramid and the carving of the iconic Sphinx, cementing his legacy in the annals of ancient Egypt. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/45982

Prince Ankhhaf, a distinguished figure of Egypt’s Old Kingdom during the Fourth Dynasty (circa 2600 BCE), is believed to have been the son of Sneferu, though his mother’s identity remains unknown. Despite holding the prestigious title of “eldest king’s son of his body,” it was his half-brother Khufu who ascended to the throne after Sneferu. Alternatively, there is a possibility that Ankhhaf was the son of Huni, which would make him Sneferu’s half-brother.

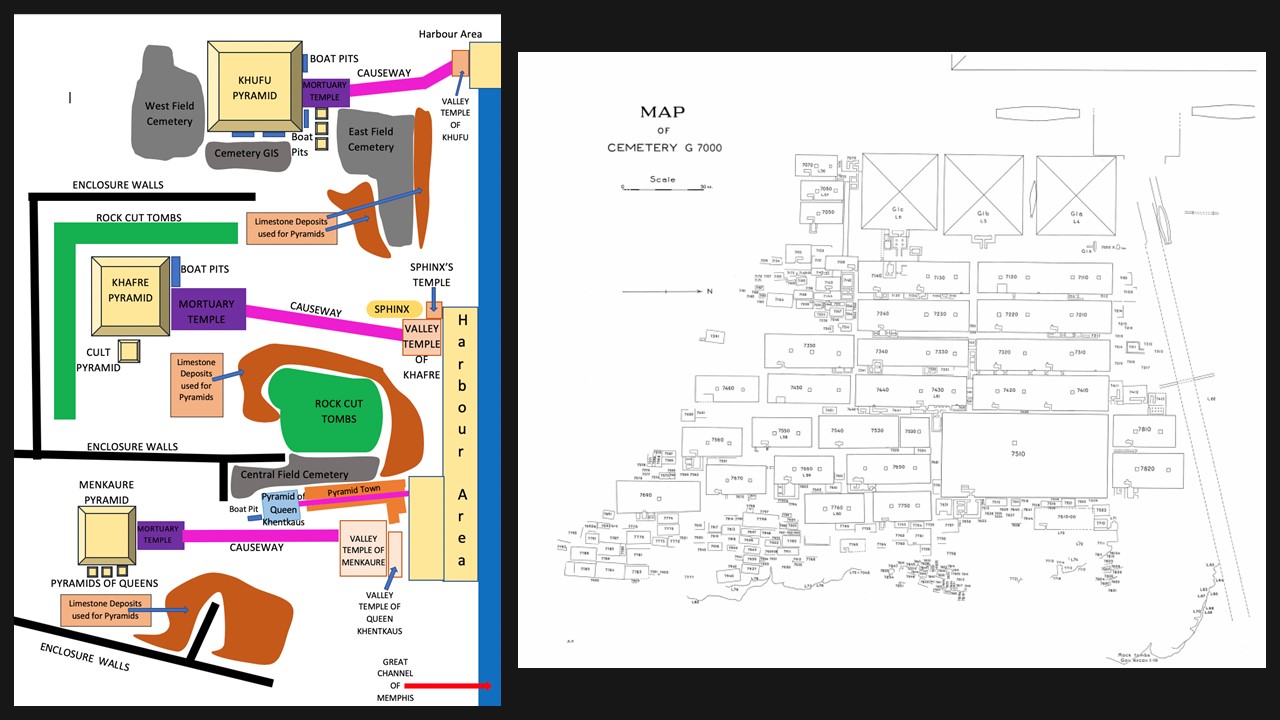

The Prince served as Vizier to his half-brother Pharaoh Khufu and possibly his nephew Pharaoh Khafre. Renowned for his architectural prowess, Ankhhaf played a crucial role in the later stages of the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza, overseeing the delivery of Tura White Limestone from quarry to port and ensuring its placement atop the pyramid’s limestone base. Egyptologists speculate that he also contributed architecturally to the Great Sphinx, another iconic structure in Giza. Ankhhaf’s familial ties were equally noteworthy; he married his half-sister Princess Hetepheres, with whom he had a daughter, also named Princess Hetepheres. His own tomb, Mastaba G7510 in the Eastern Cemetery of Giza, is one of the largest discovered at the site, reflecting his high status and enduring legacy in ancient Egyptian history.

Ankhhaf’s mastaba had a mudbrick chapel attached to its east side, oriented in such a way that it faced the chapel’s entryway. The chapel walls were covered in exquisitely modelled low relief sculptures, exemplary representations of Old Kingdom artistry, and characterized by their detailed and realistic depictions. These reliefs primarily adorn the walls of the chapel within the mastaba and depict various scenes that illustrate both daily life and ceremonial activities. The scenes feature intricate details, such as the rendering of human figures, animals, and hieroglyphic inscriptions, providing a fragmentary narrative of Ankhhaf’s life and his contributions. These reliefs also serve a symbolic function, intended to ensure the deceased’s safe passage to the afterlife and to perpetuate his memory and legacy. The craftsmanship of these sculptures demonstrates the high level of skill possessed by the artisans of the time and offers valuable insights into the aesthetic and cultural values of ancient Egypt during the 4th Dynasty.

The Bust of Prince Ankhhaf was discovered in 1925 during an excavation by the Harvard University–Museum of Fine Arts Expedition in the eastern cemetery at Giza. The excavation revealed the bust in the tomb’s chapel, an area rich with artefacts and inscriptions that shed light on the life and status of Ankhhaf. This significant find was awarded to Boston by the Egyptian Antiquities Service in gratitude for the Harvard-Boston Expedition’s painstaking work to excavate and restore objects from the tomb of Queen Hetepheres. It was transported to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where it remains one of the museum’s prized pieces, offering a tangible connection to Egypt’s ancient past. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/45982

The bust of the Egyptian Prince Ankhhaf is renowned for its striking realism, a characteristic that sets it apart from other contemporary Egyptian art. Carved from limestone and originally coated with a thin layer of plaster, the bust portrays Ankhhaf with a remarkable level of detail and individuality. His features, those of a mature man, are solemn and introspective, with a prominent nose, fleshy lips, and slight furrows on his forehead and the sides of his lips, suggesting a thoughtful and possibly authoritative demeanour. The eyes, which were once painted white with brown pupils and carried puffy pouches underneath, add to the lifelike quality of the sculpture. This bust not only exemplifies the artistic skills of the time but also provides a rare glimpse into the personal appearance of an individual from ancient Egypt’s elite class.

For a Student Activity inspired by the Bust of Prince Ankhhaf, please… Check HERE!