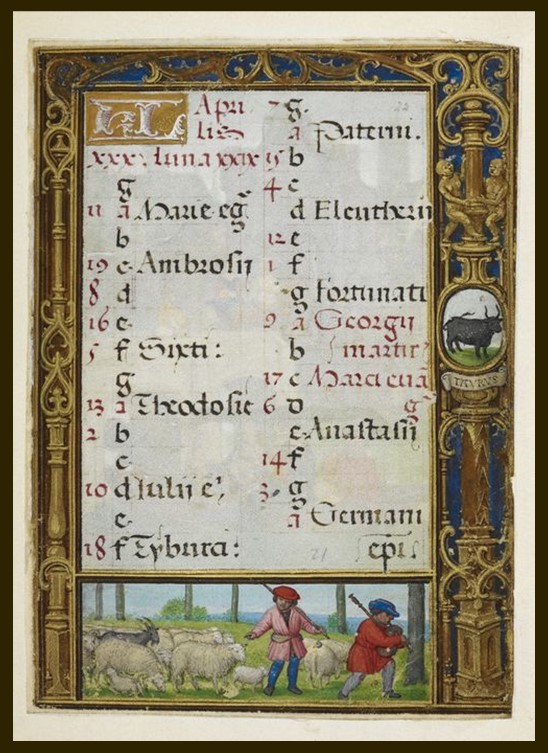

Book of Hours, known as the Golf Book, May (f. 22v),c. 1540, 30 Parchment leaves on paper mounts, bound into a codex, 110 x 80 mm (text space: 85 x 60 mm), British Library, London, UK

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/

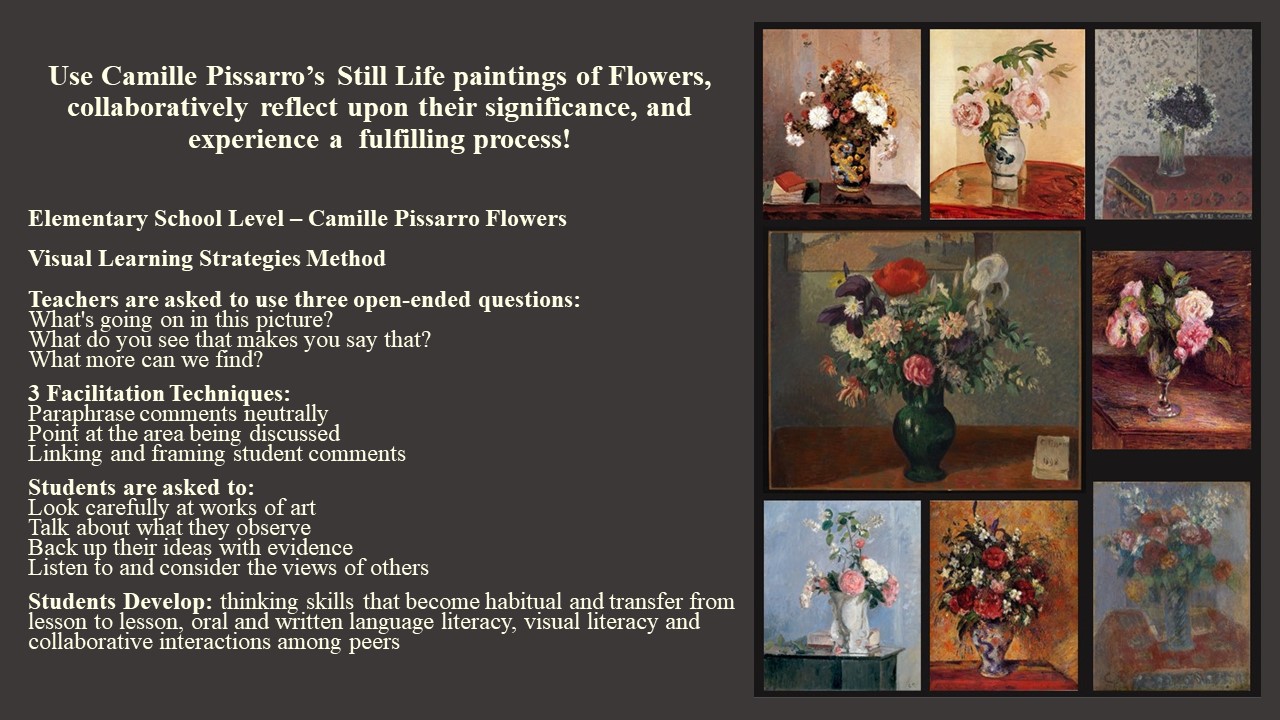

The American children’s poet Annette Wynne introduces us to charming spring with… May / Has such a winsome way, / Loves to love and laugh and play, / To be pretty all the day, / Never loves to sulk and frown, / As April does; when rain comes down, / May is sorry, says: “Rain, please / Go away soon, flowers and trees / Love the merry shining sun, / Want to laugh now, every one, / For the happy time’s begun.” / All you people who love play, / Love to love the livelong day, / Do you not love May / With her winsome way? The artist of the Golf Book, one of the finest manuscript illuminators of the Northern Renaissance introduces us to the month of May with an amazing miniature… Let’s celebrate with Simon Bening’s May…a day of boating, merriment, and joy! https://discoverpoetry.com/poems/may-poems/

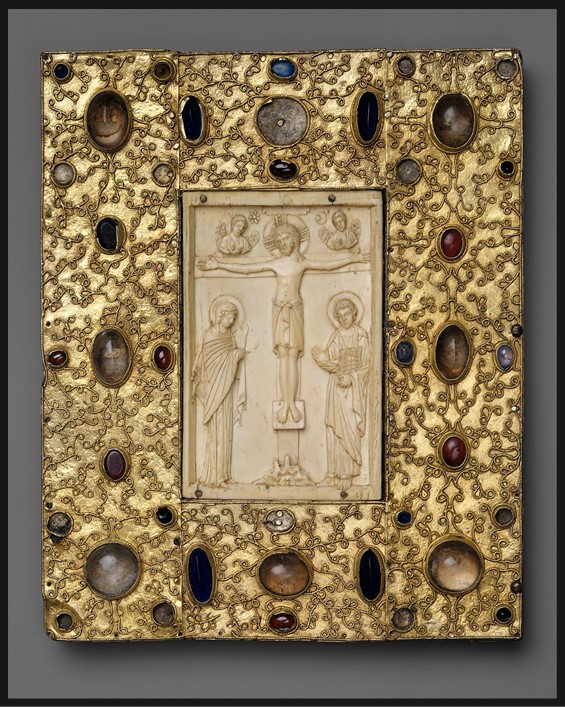

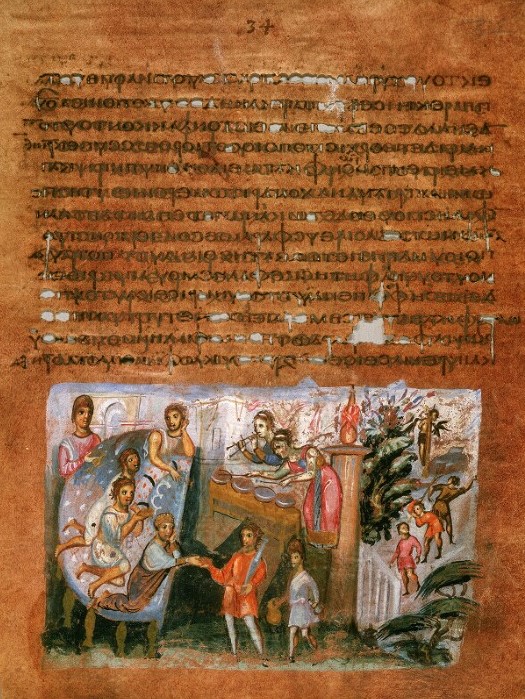

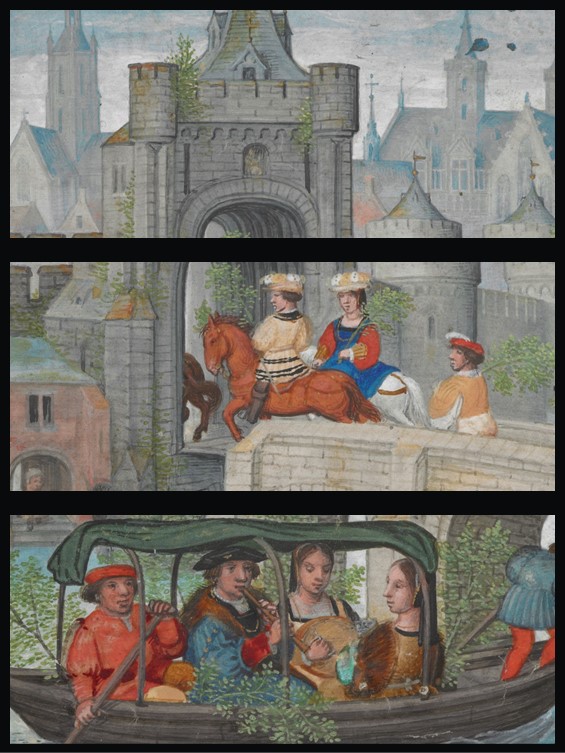

Folio 22v of the Golf Book, showing the Month of May, is one of the most glorious pages Simon Bening, the renowned Flemish artist from the Netherlands, ever created. It is a characteristic Renaissance Maying scene in its depiction of a spring landscape (Bening is known for his landscapes), with green leaves, and branches of greenery… and much more! At first glance, it presents two distinctive scenes related to May Day and a glorious river-side cityscape background scene of fortification walls, several well-constructed secular buildings, and what seems like two impressive Gothic churches. It also includes an anecdotal scene of a small gate leading to the river and a young going down the gate steps leading to the river with a container in each hand, perhaps to fill them with water… so typical Flemish! http://www.digitalmedievalist.com/2004/05/01/its-may-2/ and https://www.moleiro.com/en/books-of-hours/the-golf-book-book-of-hours/miniatura/159

Book of Hours, known as the Golf Book, May (f. 22v, details),c. 1540, 30 Parchment leaves on paper mounts, bound into a codex, 110 x 80 mm (text space: 85 x 60 mm), British Library, London, UK

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/

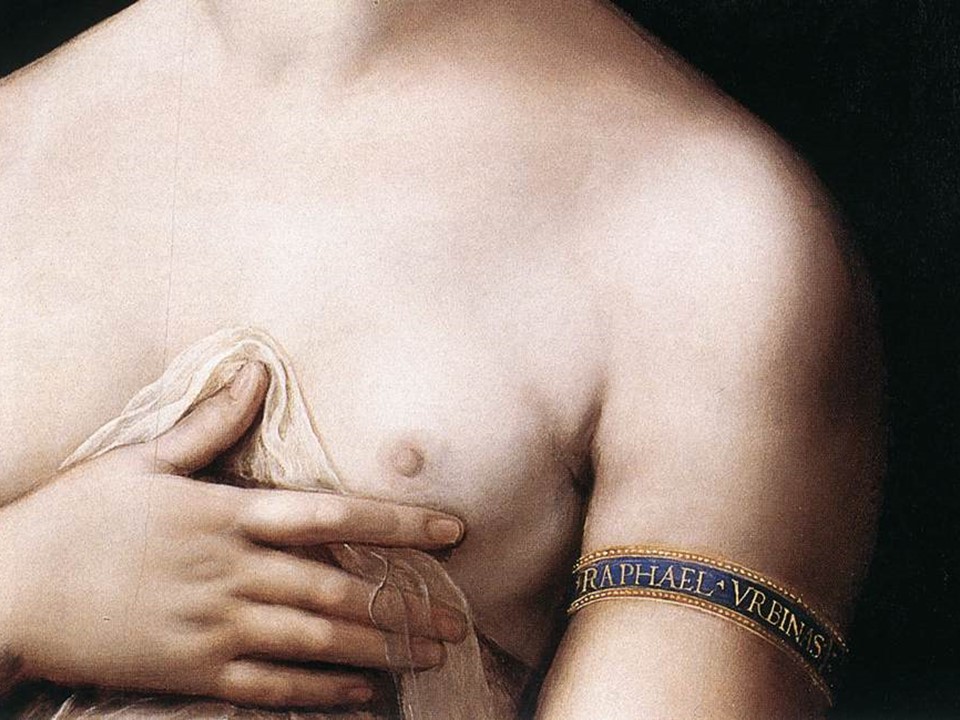

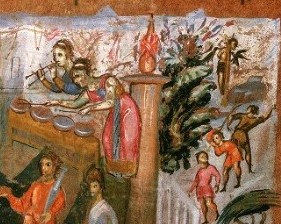

The main scene, in the foreground of the composition, depicts a May Day boating trip along the local canals. In this scene, two boatmen, one at each end of the boat, are rowing a nobleman and two well-dressed ladies along a river, just about to glide under an impressive arched bridge. Enjoying the trip are a man dressed in a large, loose French gown with a sable collar, playing, appropriately I would add, an ambiguous-looking wind instrument that could be a flute, and two women, dressed in gold-toned garments, one of whom plays the lute, equally appropriate for a female, with a plectrum. The boat is filled with flowering branches reminding the viewer that this is a May Day excursion indeed. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/ and https://www.moleiro.com/en/books-of-hours/the-golf-book-book-of-hours/miniatura/159

Book of Hours, known as the Golf Book, May (f. 22v, detail),c. 1540, 30 Parchment leaves on paper mounts, bound into a codex, 110 x 80 mm (text space: 85 x 60 mm), British Library, London, UK

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/

Book of Hours, known as the Golf Book, May (f. 22v, detail),c. 1540, 30 Parchment leaves on paper mounts, bound into a codex, 110 x 80 mm (text space: 85 x 60 mm), British Library, London, UK

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/

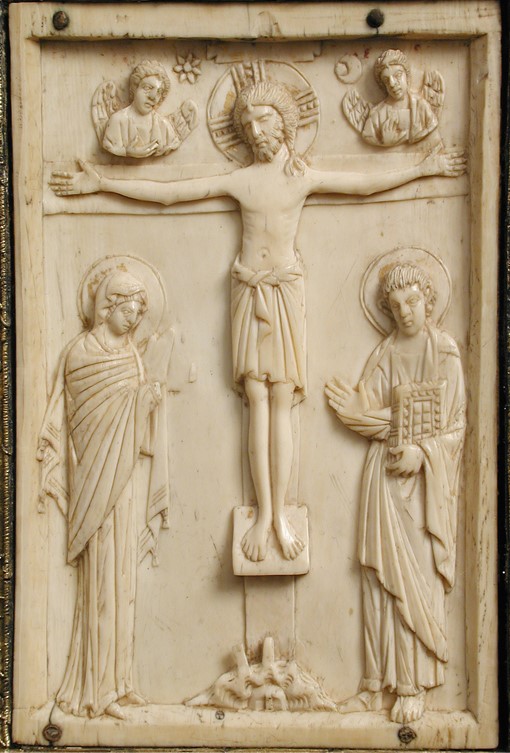

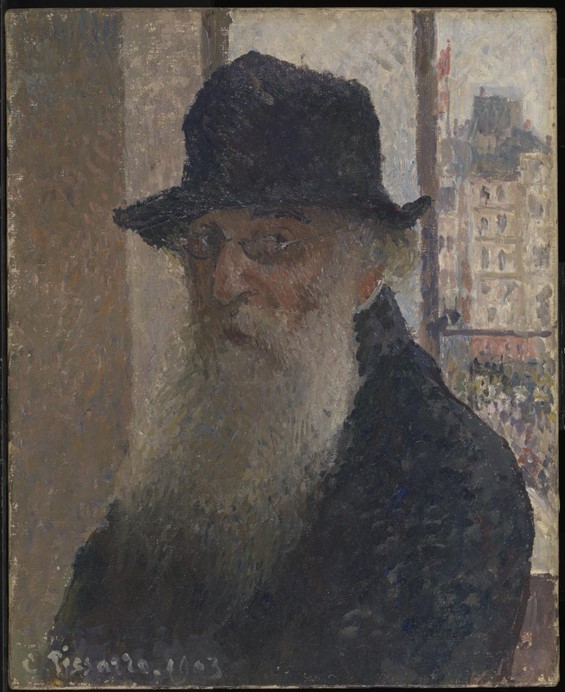

The middle ground scene focuses on the activity taking place on the bridge connecting the city to the riversides. Horses are depicted crossing the bridge, and Bening directs the attention of the viewer to an aristocratic couple, well-dressed, crowned with large, white flowers and carrying branches. They seem to be returning “home” after a day of merriment in the countryside. Were they part of the elegant group of riding aristocrats depicted strolling through the wood in the bas-de-page scene of folio 23r? It would have been interesting to know what Simon Bening thought! https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/

For a PowerPoint on the Golf Book, please… Check HERE!

For references to Student Activities on Simon Bening’s May Day page, please… Check HERE!

Book of Hours, known as the Golf Book, May (f. 22v and 23r),c. 1540, 30 Parchment leaves on paper mounts, bound into a codex, 110 x 80 mm (text space: 85 x 60 mm), British Library, London, UK

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/calendars/page/11/