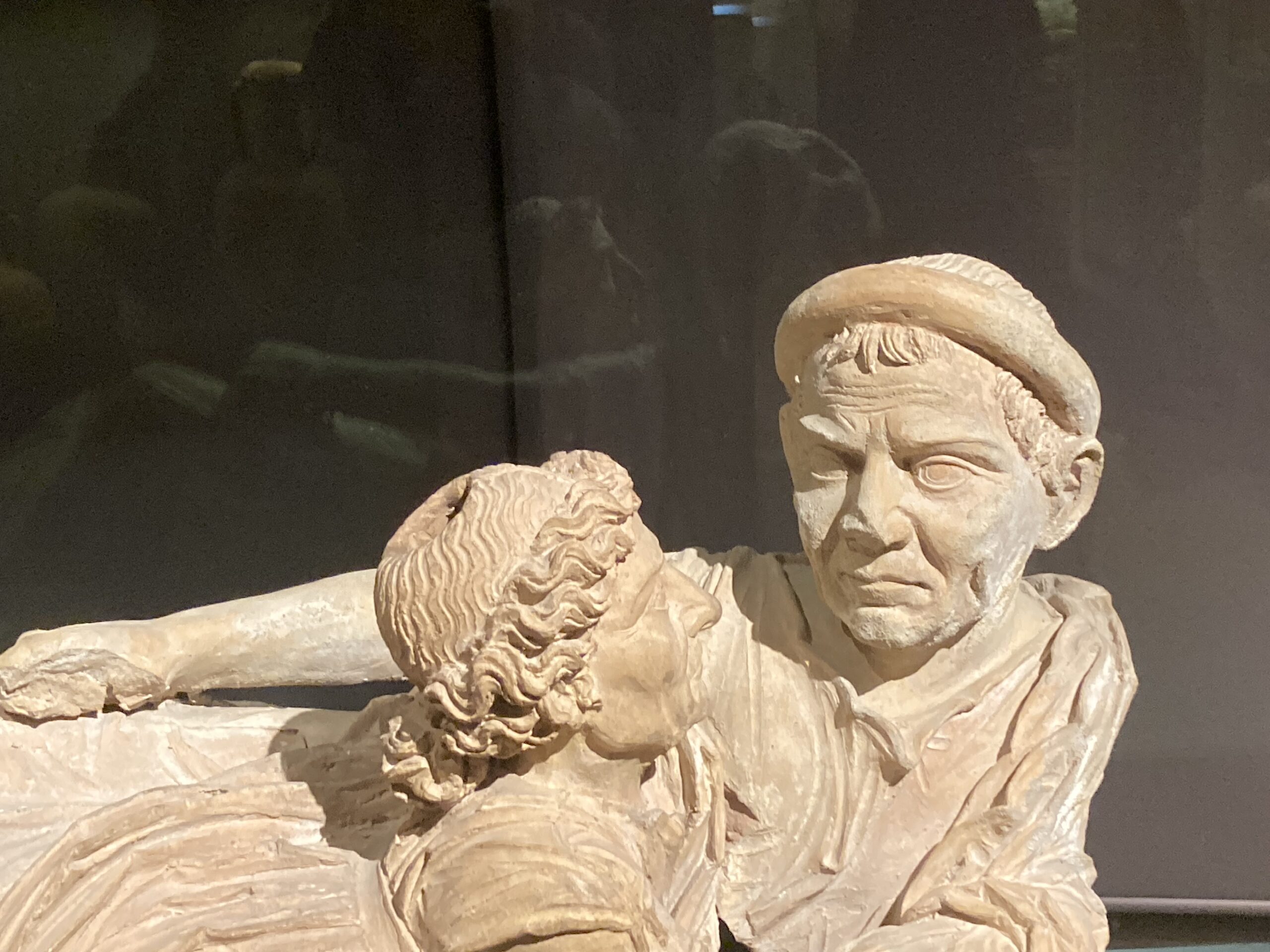

Portrait of Isabella Brant, 1626, Oil on canvas, 86×62 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Isabella Brant (1591–1626) was the first wife of the celebrated Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens and a woman of notable grace and social standing in early 17th-century Antwerp. Born into a prominent family, she was the daughter of Jan Brant, a respected city official and scholar, which placed her at the heart of Antwerp’s intellectual and cultural life. Isabella married Rubens in 1609, a union that combined affection with advantageous connections, strengthening the artist’s ties to influential circles in the city. Known for her charm, wit, and refinement, Isabella was admired not only as a devoted wife and mother—she and Rubens had three children together—but also as a figure who embodied the elegance and sophistication of her time. Her life, though tragically brief, left a lasting impression on those around her and continues to be remembered as an integral part of Rubens’ story.

The artist painted his first wife, Isabella Brant, numerous times, leaving behind a vivid record of her presence in his life. One of their earliest joint portrayals is the famous Honeysuckle Bower (1609), a double portrait celebrating their marriage with symbolic gestures of love and harmony. Beyond this, Rubens created several individual portraits of Isabella, including the elegant Portrait of Isabella Brant now in the Uffizi Gallery, painted around 1620, where her calm dignity and refined beauty are captured with remarkable sensitivity. Her likeness also appears in drawings and informal sketches, suggesting she was both a willing sitter and a constant source of inspiration. Even after her untimely death in 1626, Rubens continued to evoke her image in allegorical works, blending memory with artistry. Taken together, these portraits reveal not only Isabella’s grace but also the depth of affection and admiration with which Rubens regarded her, preserving her legacy through his masterful brush.

Portrait of Isabella Brant, c.1621-1622, Black and red chalk, with some brown wash, heightened with white, on light grey-brown paper, 381×294 millimeters, British Museum, London, UK

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1893-0731-21

Rubens’s Portrait of Isabella Brant in Galleria degli Uffizi, in Florence, Italy, shows the artist’s first wife at half-length, turned slightly left against a neutral setting punctuated by a stone column and a sweep of reddish drapery. She wears a sumptuous dark gown with jewels and chains, her alert gaze and faint smile animating the likeness. Painted circa 1625–26 in oil on panel (about 86 × 62 cm), the work likely entered Medici collections as a gift sent in 1705 by the Elector of Düsseldorf to Ferdinando de’ Medici and has been recorded in the Uffizi since the 18th century.

Aesthetically, the painting distills Baroque ideals into an intimate format… supple, luminous flesh set against a subdued ground, softly modelled forms created by confident, fluid brushwork, and a poised interplay of light and shadow that gives Isabella psychological presence as well as social stature. Rather than theatrical gesture, Rubens opts for restrained dignity, rich fabrics, tactile surfaces, and a living, breathing immediacy, embodying the Baroque’s preference for sensuous color, dynamism of paint, and persuasive naturalism in the service of status, piety, and affection.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) stands as one of the greatest masters of the Baroque, celebrated not only for his monumental altarpieces and mythological scenes but also for the intimacy and vitality of his portraits. In his likenesses, Rubens combined acute psychological insight with a painterly richness that gave his sitters both dignity and immediacy. His portraits of Isabella Brant exemplify this mastery: the fluidity of his brushwork, the luminosity of skin tones, and the nuanced handling of fabric and jewelry all serve to elevate the sitter while preserving her individuality. Rubens’s genius lay in his ability to balance grandeur with naturalism, portraying figures of status with humanity and warmth. Through such works, he transformed portraiture into a vibrant art form that communicated not only outward likeness but also inner character, securing his reputation as one of the most accomplished portraitists of his time.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Rubens and Isabella Brant, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/detail/HistoricOrArtisticProperty/0900129546?utm_source=chatgpt.com and https://www.artchive.com/artwork/portrait-of-isabella-brant-peter-paul-rubens-c-1625-26/ and https://www.virtualuffizi.com/peter-paul-rubens.html