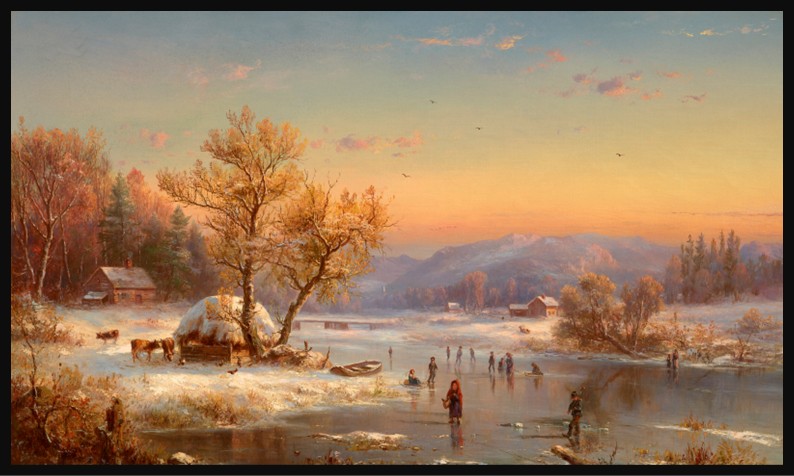

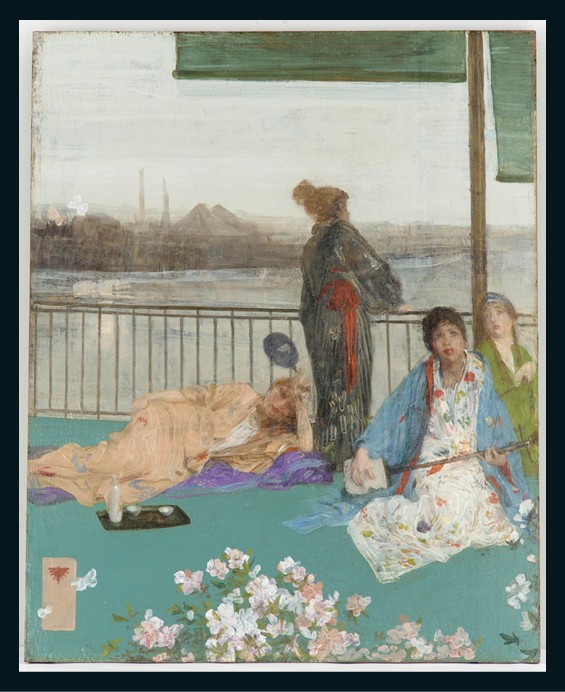

Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony, 1864-1870; additions 1870-1879, Oil on Wood Panel, 61.4 × 48.5 cm, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington DC, USA https://asia-archive.si.edu/object/F1892.23a-b/

During the latter half of the 19th century, the allure of Japanese art swept through the Western art world, influencing countless artists and intellectuals. James Abbott McNeill Whistler, a pivotal figure in this movement, embraced Japonisme with fervor, blending its aesthetic with inspirations drawn from ancient Greek sculpture, music, and dance. One of the most captivating results of this cultural synthesis is Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony, a painting that encapsulates Whistler’s mastery of harmony and elegance. In this work, elegant female figures, poised in a dreamlike composition, echo the refined simplicity of Japanese ukiyo-e prints and the timeless grace of classical antiquity, offering viewers a serene yet dynamic tableau that transcends cultural boundaries.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) was an American-born artist who became a pivotal figure in the art world of the late 19th century. Although he was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, Whistler spent much of his professional life in Europe, particularly in London and Paris. He initially enrolled at the United States Military Academy at West Point but left to pursue art, studying at the École Impériale and under Charles Gleyre in Paris. Known for his sharp wit and flamboyant personality, Whistler was as much a celebrity as he was an artist. He was a pioneering figure in the art world, advocating for the “art for art’s sake” philosophy and challenging conventional ideas about the purpose of art. His works, particularly his portraits and tonal landscapes, have left an indelible mark on modern art.

Whistler’s art is defined by a masterful interplay of realism and abstraction, emphasizing harmony, balance, and the emotional resonance of his compositions. His works are often characterized by muted colour palettes, delicate brushwork, and a focus on tonal subtleties that evoke a sense of mood and atmosphere. Drawing inspiration from music, he linked his art to musical arrangements, prioritizing rhythm, tonal harmony, and visual balance over detailed narratives. Whistler’s compositions often employed a poetic simplicity, where every element was meticulously placed to create a sense of elegance and refinement. His ability to transform ordinary scenes into evocative, almost transcendent experiences solidified his reputation as a pioneering artist whose work continues to resonate for its understated beauty and sophistication.

The painter’s passion for Japanese art was a defining aspect of his artistic identity and a significant influence on his work. During the late 19th century, as Japonisme swept through Europe, Whistler became captivated by the elegance and simplicity of Japanese aesthetics, particularly the ukiyo-e woodblock prints of artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige. These influences manifested in his compositions through asymmetrical arrangements, flattened perspectives, and an emphasis on pattern and line. Whistler’s Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony is a quintessential example of his Japonist inspiration, blending the poise and serenity of Japanese art with his signature tonal harmony. By integrating Japanese elements into his work, Whistler not only enriched his visual language but also helped introduce and popularize Japanese aesthetics in Western art, leaving a lasting impact on the modernist movement.

Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony by James McNeill Whistler is a striking example of the artist’s mastery of tonal harmony and his innovative blending of Eastern and Western artistic traditions. Painted between 1864 and 1870, the work depicts four female figures positioned on a balcony, their elegant forms and serene postures suffused with a dreamlike quality. The composition is dominated by soft greens, whites, and muted flesh tones, creating a delicate interplay of light and shadow that enhances the painting’s tranquil atmosphere. Inspired by Japanese aesthetics, particularly the ukiyo-e prints he admired, Whistler incorporates asymmetry, flattened perspectives, and an emphasis on line and pattern into the scene. The inclusion of Japanese screens and textiles within the composition further highlights the artist’s fascination with Japanese art and design. This painting, rich in both detail and abstraction, exemplifies Whistler’s ability to create works that are simultaneously intimate and evocative, inviting viewers into a space of quiet contemplation.

For a PowerPoint Presentation titled James Abbott McNeill Whistler, 1834-1903 Women in Asian Costumes, please… Check HERE!

Here is a 2022 Teacher Curator BLOG POST dedicated to Whistler and titled The Princess from the Land of Porcelain by James Abbott McNeill Whistler… https://www.teachercurator.com/19th-century-art/the-princess-from-the-land-of-porcelain-by-james-abbott-mcneill-whistler/?fbclid=IwY2xjawHpvEdleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHeks8antME7C09qYEjRXOCmNfAVpuitdsk_7bUckVFT4h83W6yWCHEIFwg_aem_IbgjlirTqcITLtBwsS_x-g

Bibliography: https://asia-archive.si.edu/object/F1892.23a-b/