The Cluny Museum, officially known as the Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge, is a captivating institution located in the heart of Paris, France. Housed in the former Cluny Abbey, a medieval Benedictine monastery, the museum is dedicated to the preservation and display of artifacts from the Middle Ages. Its rich collection spans from the Late Roman Period to the 16th century and includes a diverse range of artworks that provide a fascinating glimpse into medieval life. The architecture of the Cluny Museum itself is a marvel, blending the 20th century, Medieval, and Renaissance elements, with beautiful gardens adding to its charm. Visitors can explore the intimate courtyards, chapels, and thermal baths, which are among the best-preserved Roman baths in France. The Cluny Museum stands as a unique space, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the art, history, and culture of the medieval period in an enchanting setting.

https://joinusinfrance.com/episode/episode-8-cluny-museum-walking-tour/

Visitors to the Cluny Museum in Paris can explore a rich and diverse collection of artifacts from the Middle Ages. https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/en/ Some of the highlights include:

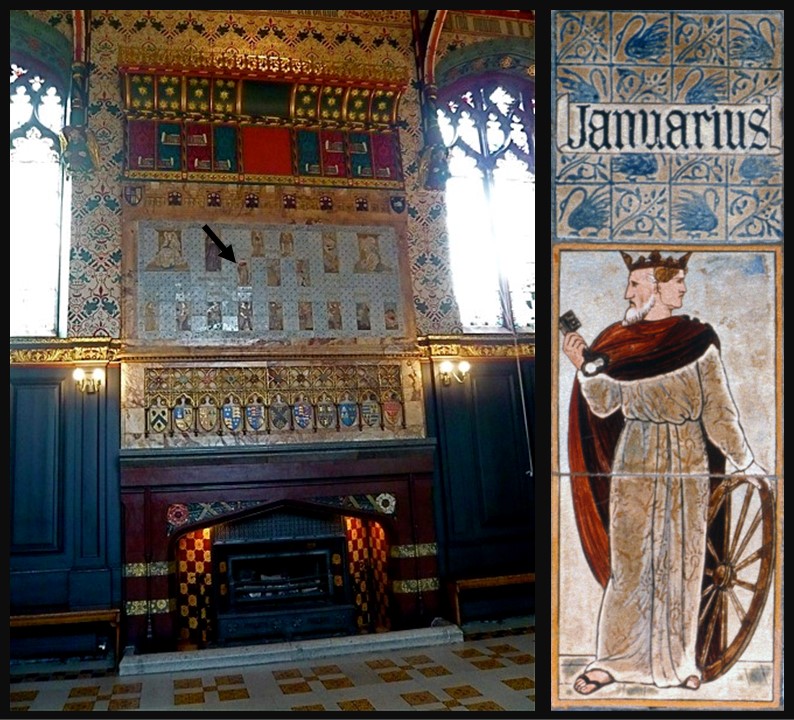

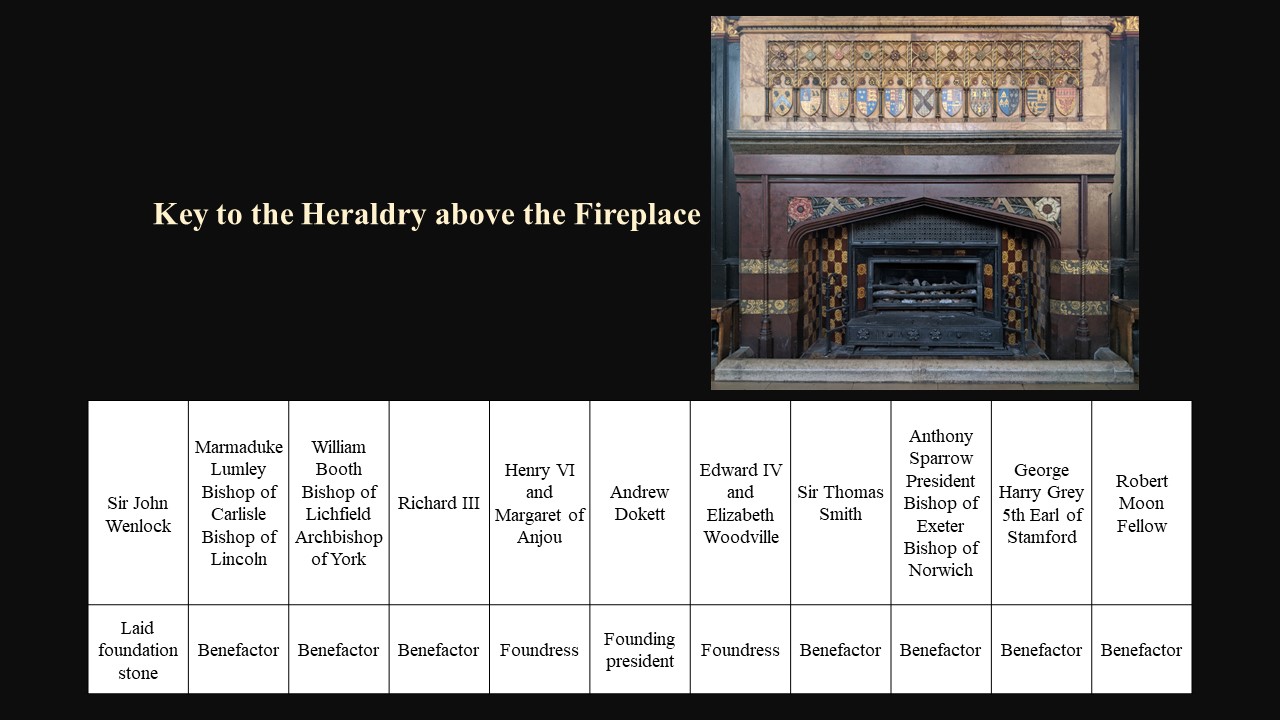

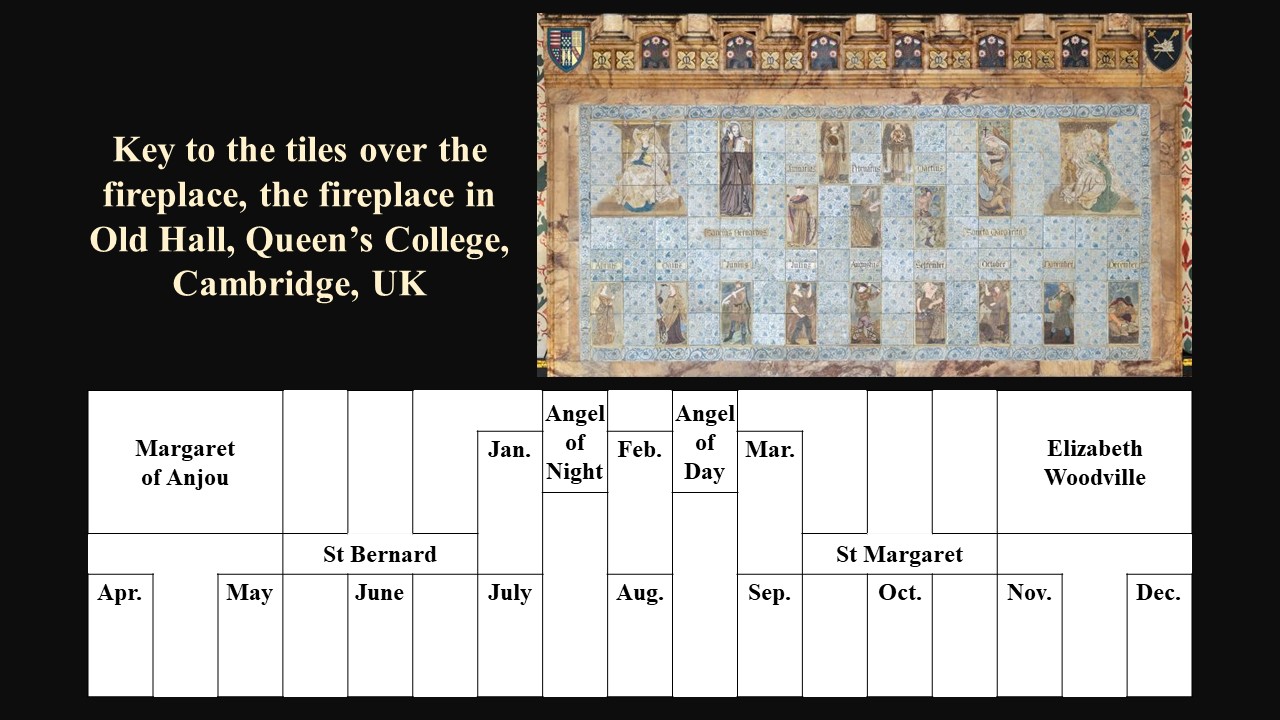

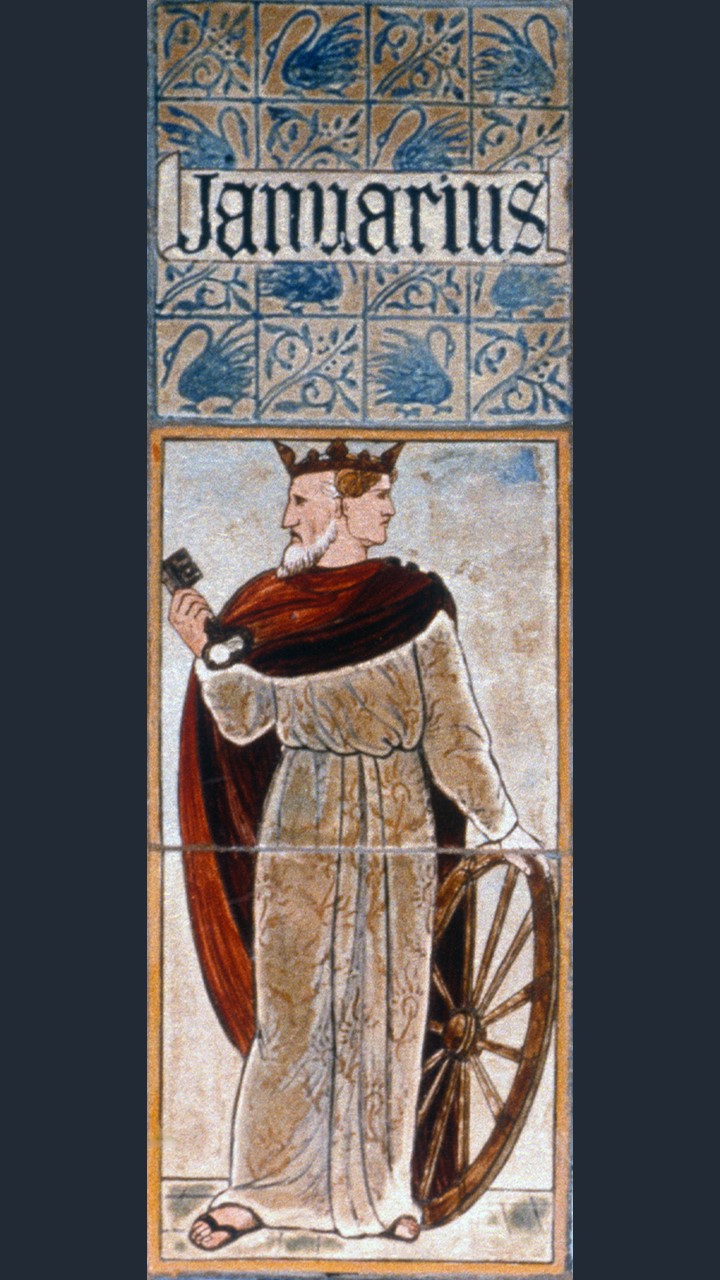

Medieval Sculptures and Architectural Fragments: The museum houses a remarkable collection of medieval sculptures, including statues, reliefs, and architectural fragments from churches and cathedrals. The sculptures depict saints, biblical figures, and scenes from religious narratives, revealing the profound influence of Christianity on medieval art. Additionally, the architectural fragments provide insights into the grandeur of medieval structures, allowing visitors to appreciate the ornate details and exquisite craftsmanship that adorned sacred spaces like the Notre Dame of Paris or Sainte-Chapelle.

Illuminated Manuscripts: The Cluny Museum features a splendid collection of illuminated manuscripts, showcasing the intricate and detailed illustrations found in medieval books. These manuscripts often include religious texts, literary works, and scientific treatises.

Stained Glass Windows: The museum displays a selection of medieval stained glass windows, offering a glimpse into the stunning visual artistry that adorned churches and cathedrals during the Middle Ages. These windows, meticulously crafted with vibrant colors and intricate designs, provide a vivid representation of the storytelling and symbolism embedded in medieval Christian traditions.

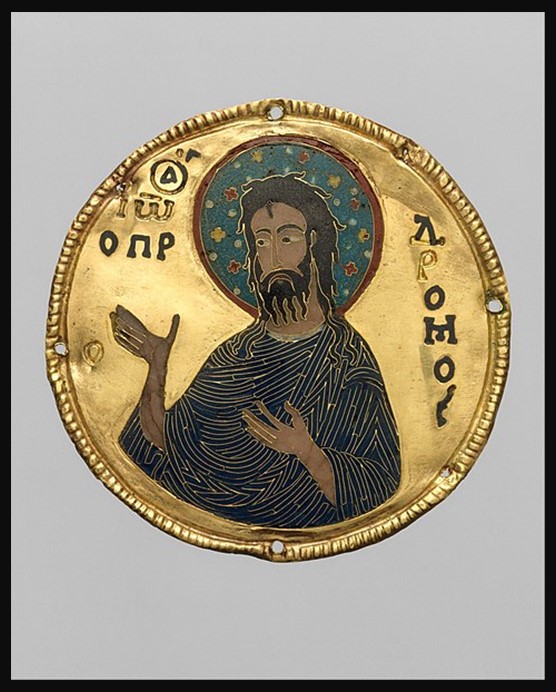

Everyday Life Artifacts: Visitors can explore a variety of everyday objects from medieval life, such as ceramics, textiles, and metalwork. These artifacts provide insights into the daily lives, customs, and technologies of people during the medieval period.

The Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries: This famous series of six tapestries is considered a masterpiece of medieval art. Each tapestry represents one of the senses, and the intricate designs and vibrant colors are a testament to the craftsmanship of the time.

Roman Baths, Gardens, and Courtyards: The Cluny Museum is situated on the site of ancient Roman baths, and visitors can explore the well-preserved frigidarium (cold room) and caldarium (hot room), gaining an understanding of Roman engineering and architecture. Additionally, the museum features charming gardens and courtyards, offering peaceful spaces for visitors to relax and enjoy the historic surroundings.

The Cluny Museum in Paris offers a unique and alternative experience for visitors exploring the French capital due to its singular focus on the Middle Ages. Amidst the iconic landmarks and modern attractions of Paris, the museum provides a serene escape into the rich tapestry of medieval history, art, and culture. Its diverse collection offers an immersive journey into a bygone era. The atmospheric setting of the former Cluny Abbey, complete with Roman baths and picturesque gardens, enhances the distinctive charm of this museum. It provides a more intimate and specialized encounter, allowing visitors to delve into the intricate details of medieval life, religious practices, and artistic achievements, creating an enriching contrast to the contemporary allure of Paris.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Masterpieces from the Cluny Museum, please… Check HERE!