Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, c. 1320, Fresco, Lower Church, View of the south arm of the western transept, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy https://www.wga.hu/html_m/l/lorenzet/pietro/1/1vault/1entry.html

Pietro Laurati (commonly known as Pietro Lorenzetti), an excellent painter of Siena, proved in his life how great is the contentment of the truly able, who feel that their works are prized both at home and abroad, and who see themselves sought after by all men, for the reason that in the course of his life he was sent for and held dear throughout all Tuscany… and Umbria, if I may add, as his Palm Sunday fresco scene in Assisi is truly magnificent! https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm

Pietro Lorenzetti was a renowned Sienese painter of the Early Renaissance, known for his expressive and naturalistic approach to religious art. Alongside his younger brother, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, he played a crucial role in advancing Sienese painting by incorporating elements of spatial depth and emotional realism, bridging the gap between Byzantine traditions and the emerging Renaissance style. His most celebrated works include the frescoes in the Lower Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, notably the Palm Sunday scene and the Crucifixion of Christ, which showcase his mastery of dramatic composition and human expression. His contributions, along with those of Duccio and Simone Martini, helped define the distinctive elegance and narrative richness of Sienese art. Like many artists of his time, it is believed that Pietro fell victim to the Black Death around 1348, marking the end of an influential career that significantly shaped early Italian painting.

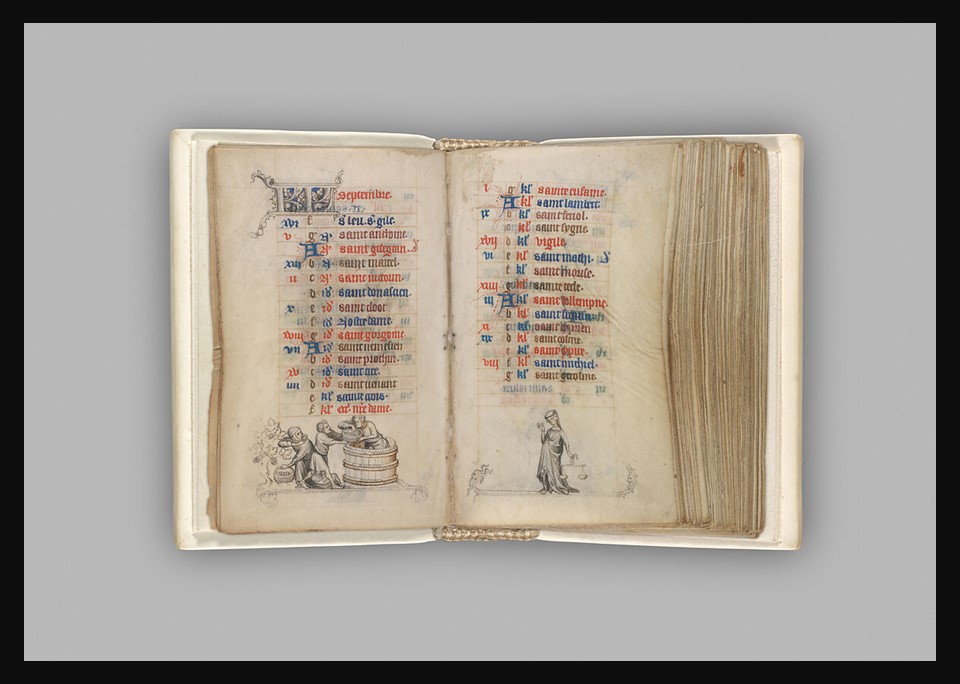

View of the south arm of the western transept, c. 1320, Fresco, Lower Church, View of the south arm of the western transept, San Francesco, Assisi https://arsartisticadventureofmankind.wordpress.com/tag/basilica-of-saint-francis-of-assisi/

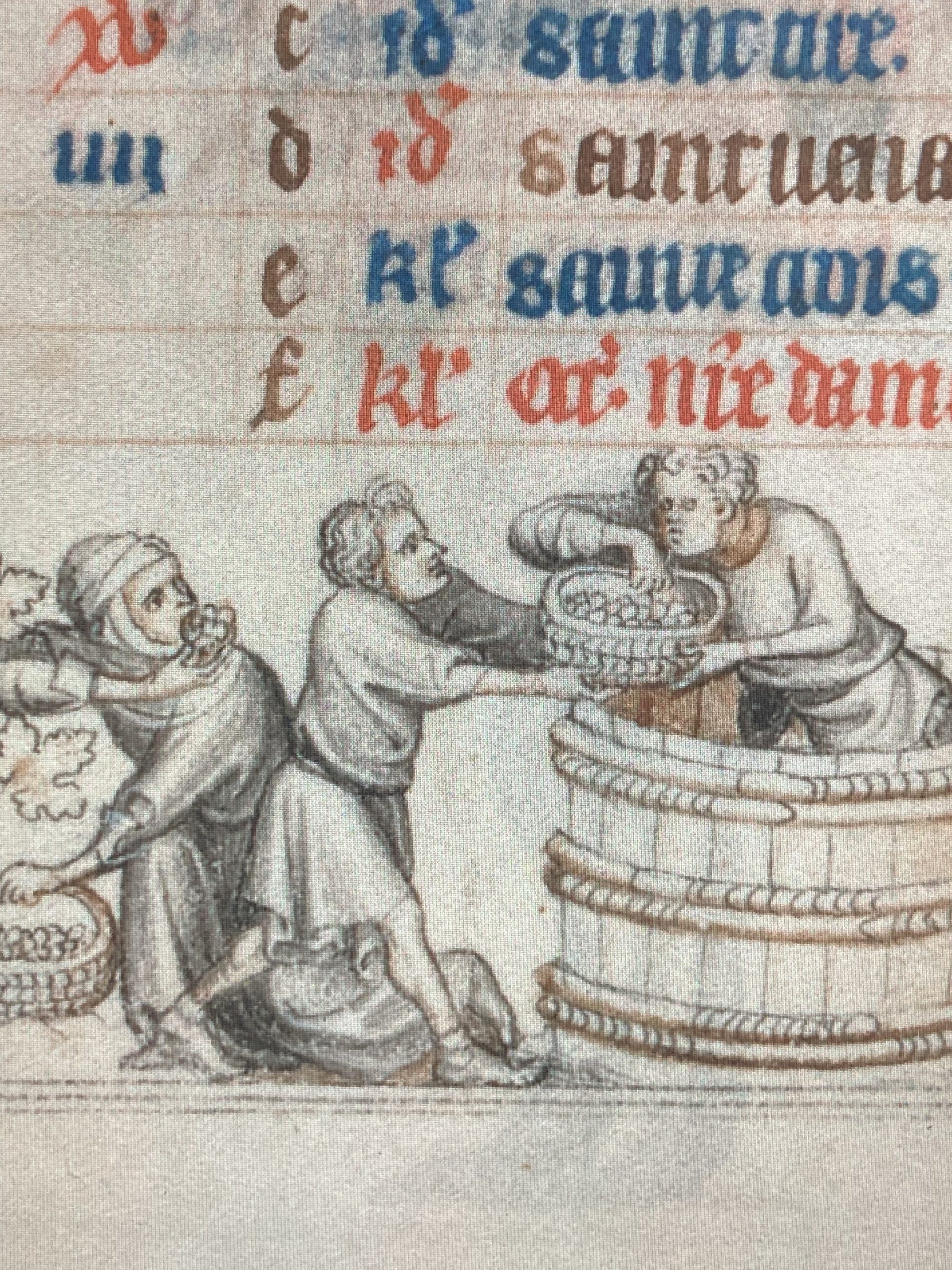

The artist’s frescoes in the Lower Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi are among the most significant works of early 14th-century Italian painting. Commissioned as part of the extensive decorative program honoring St. Francis of Assisi, these frescoes depict various scenes from the Passion of Christ. Created between 1320 and 1340, they showcase Lorenzetti’s innovative approach to storytelling, blending the spiritual intensity of Gothic tradition with a heightened sense of realism. His compositions introduce a more profound emotional depth and spatial complexity compared to earlier Sienese paintings. Unfortunately, time and environmental factors have caused some deterioration, but the surviving sections still provide a remarkable glimpse into Lorenzetti’s mastery of fresco technique and his contribution to the evolution of Italian art.

The Deposition, c. 1320, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy https://arsartisticadventureofmankind.wordpress.com/tag/basilica-of-saint-francis-of-assisi/

Aesthetically, Lorenzetti’s frescoes in Assisi are striking for their dramatic use of chiaroscuro, spatial illusionism, and expressive human figures. Unlike the rigid and hieratic figures of earlier Byzantine-style painting, his characters convey deep emotion and dynamic movement, making the biblical narratives more immediate and relatable. The Deposition of Christ, for example, is renowned for its intense sorrow, as mourners delicately cradle Christ’s lifeless body in a composition that feels both weighty and fluid. His use of architectural elements to frame and organize space enhances the sense of depth, allowing figures to appear more grounded and three-dimensional. The naturalistic drapery, individualized facial expressions, and carefully observed gestures reveal a sophisticated understanding of human emotion and physicality, marking a significant step toward the artistic advancements of the Renaissance.

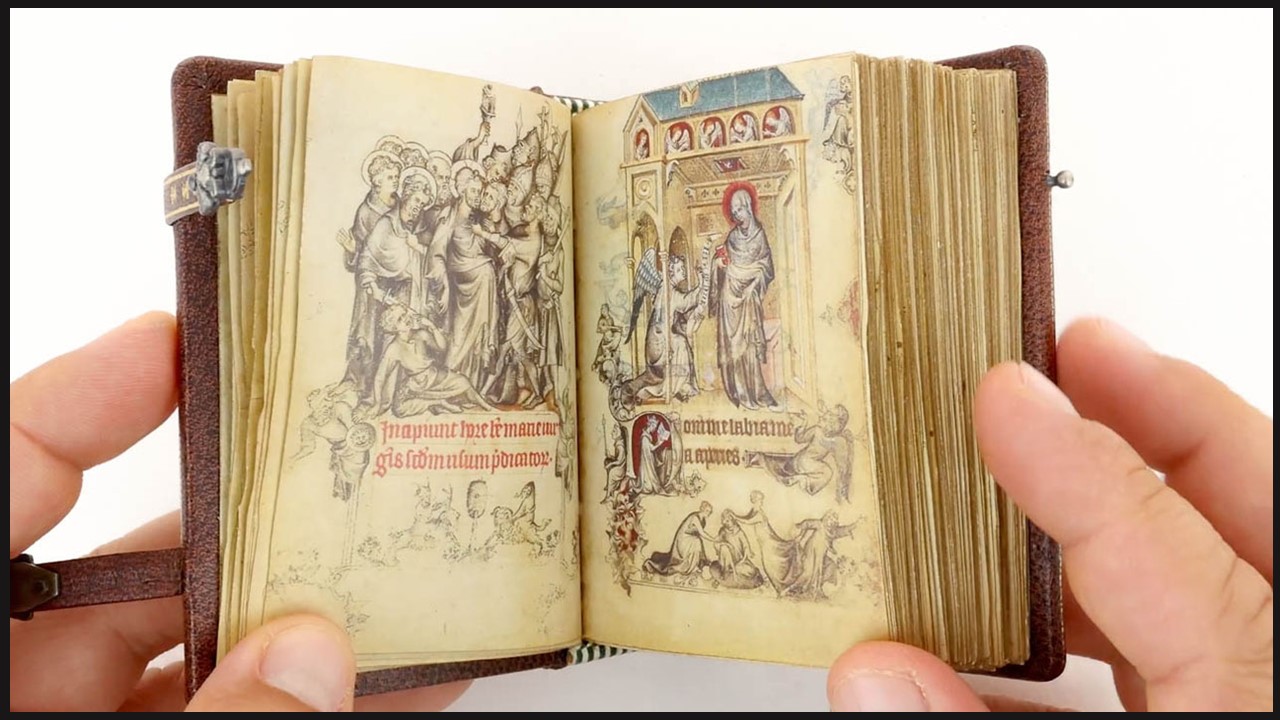

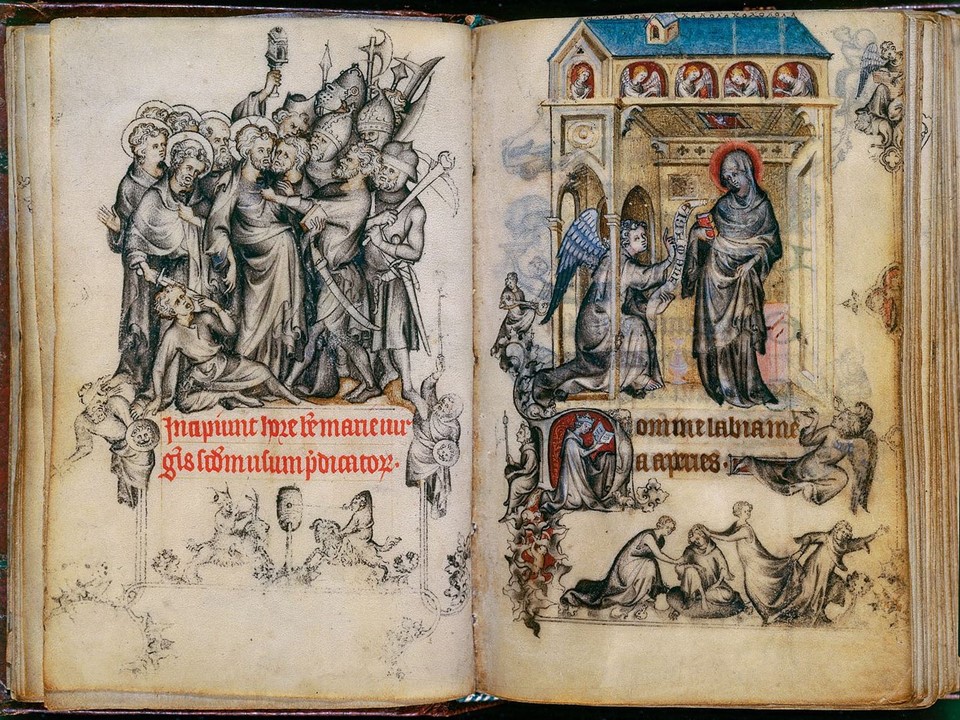

The Entry to Jerusalem fresco, part of Pietro’s cycle depicting the Passion of Christ in the Lower Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi, is a favourite example of his oeuvre, as it masterfully captures the dramatic moment when Christ enters Jerusalem, greeted by a crowd laying down garments and palm branches in reverence. The composition is notable for its structured yet dynamic arrangement, with Christ positioned centrally, riding a donkey, surrounded by his disciples and the expectant citizens of Jerusalem. Lorenzetti’s ability to create narrative clarity while maintaining a rich visual complexity is evident in the fresco’s layered depth and the variety of gestures that convey both reverence and excitement. The scene is framed by an architectural backdrop, suggesting an awareness of spatial organization, a characteristic that distinguishes Lorenzetti from earlier, more rigidly structured Byzantine-influenced compositions.

Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (details), c. 1320, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pietro_Lorenzetti_-_Entry_of_Christ_into_Jerusalem_%28detail%29_-_WGA13504.jpg

Aesthetically, Lorenzetti’s Entry to Jerusalem is remarkable for its expressive realism, and innovative spatial depth. The figures, though arranged in a relatively shallow space, are rendered with a keen sense of individualization, each face reflecting distinct emotions ranging from joy to solemn contemplation. His use of chiaroscuro adds volume and weight to the figures, making them appear more three-dimensional, a technique that anticipates the later advancements of the Renaissance. The drapery of the garments flows naturally, and the figures interact convincingly within the setting, creating a sense of immediacy and liveliness. Additionally, Lorenzetti’s handling of colour and light enhances the emotional intensity of the scene—earthy tones provide warmth and depth, while brighter highlights emphasize key focal points, such as Christ and the welcoming crowd. This fresco not only reflects Lorenzetti’s technical mastery but also underscores his role in pushing Sienese painting beyond decorative elegance into a more humanized and spatially aware visual language.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Pietro Lorenzetti’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!