Visiting the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza was an unforgettable experience, an inspiring journey through centuries of ceramic artistry. As someone with a deep appreciation for both history and design, I was truly impressed by the museum’s extraordinary collection, which showcases the global and cultural significance of ceramics in such a thoughtfully curated way. Among the many treasures, one piece that especially captivated me was a modest yet elegant Majolica plate from the 16th century, skillfully adorned with the coat of arms of the Medici of Florence. Despite its small size, just 12.3 cm in diameter, its refined craftsmanship and understated beauty spoke volumes. It offered a glimpse into The Medici in Faenza, a subtle yet powerful reminder of how far their influence reached, and how even the simplest objects can carry the weight of history with quiet grace. https://www.micfaenza.org/en/

Let’s explore the ‘how’, ‘’, ‘why’, and ‘what’ of the amazing ‘Majolica Plate decorated with the coat of arms of the Medici of Florence’ in theInternational Museum of Ceramics in Faenzaby posing some questions!

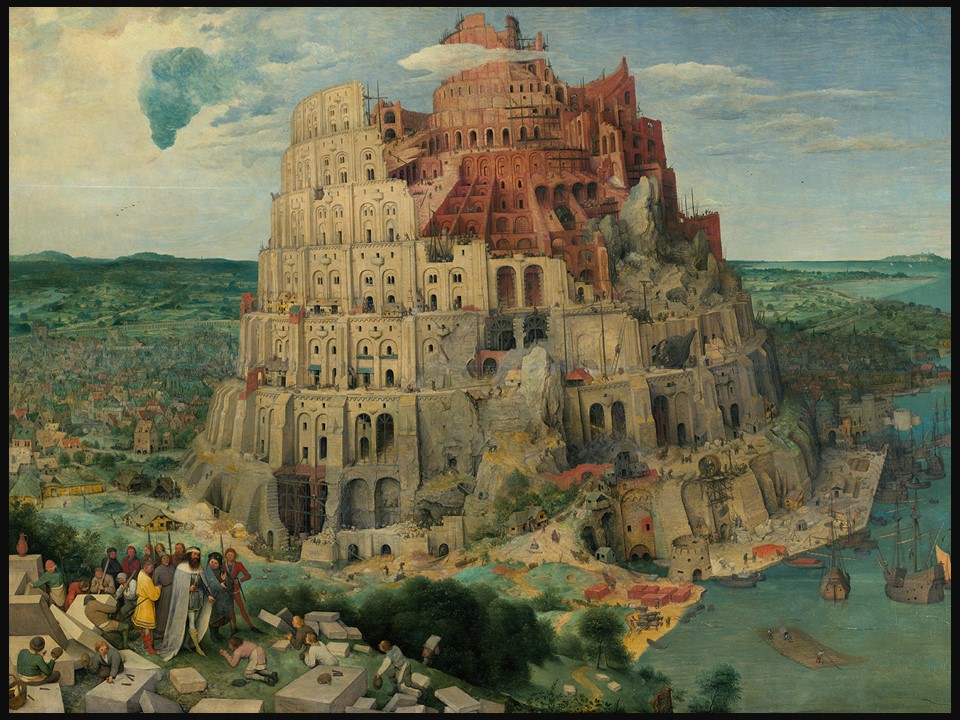

What is Majolica, and why was it significant in Renaissance Italy? A Majolica plate is a type of tin-glazed earthenware that became highly popular in Renaissance Italy for its vibrant colors and intricate designs. Made from clay and coated with a white tin glaze, the surface served as a canvas for hand-painted decoration using metallic oxide pigments, which became brilliantly glossy after firing. These plates often featured historical, mythological, or heraldic imagery—like the Medici coat of arms—and were prized for both their beauty and craftsmanship. More than just functional objects, Majolica plates were symbols of wealth, status, and artistic refinement, reflecting the cultural and political identity of their time.

What is the origin of the term “Majolica,” and how has its meaning and use evolved over time? The term “Majolica” originates from the Spanish island of Mallorca (Majorca), which was a key trading hub for ceramics between the Islamic world and Italy during the Middle Ages. Italian potters believed that the brightly colored, tin-glazed pottery imported through Mallorca came from there, and the name “Maiolica” (the Italian form) became associated with this style of earthenware. Initially, it referred specifically to the luxurious, vividly painted ceramics produced in Renaissance Italy, especially in centers like Faenza, Deruta, and Urbino. Over time, particularly in the 19th century, the term “Majolica” began to be used more broadly—and sometimes confusingly—to describe other types of colorful ceramics, including English Victorian ware with entirely different techniques. Despite this evolution, in its original sense, Majolica remains a celebrated hallmark of Italian Renaissance artistry and innovation in ceramics.

What role did the city of Faenza play in the development and prominence of Majolica earthenware? Faenza played a central role in the development and prominence of Majolica earthenware during the Renaissance, becoming one of the most important ceramic production centers in Italy. The city’s artisans were renowned for their technical skill and artistic innovation, helping to refine the tin-glazing technique that gave Majolica its brilliant, glossy surface. Faenza’s strategic location along trade routes and its strong guild traditions fostered an environment where ceramic craftsmanship could flourish. So influential was its production that the French term for fine tin-glazed pottery—faïence—derives from the name of the city. Faenza’s legacy in ceramics continues today, celebrated through institutions like the International Museum of Ceramics, which honors its rich contribution to the art form.

Why is the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza considered an important institution in the world of ceramic art and history? The International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza is considered one of the most important institutions in the world of ceramic art and history due to its vast and diverse collection, its historical significance, and its role in preserving and promoting ceramic heritage. Founded in 1908, the museum houses work from ancient civilizations to contemporary ceramic art, representing cultures from across the globe. It is especially renowned for its comprehensive display of Italian Majolica, with masterpieces from key production centers like Faenza, Deruta, and Urbino. The museum also serves as a vital center for research, education, and innovation in ceramics, hosting exhibitions, workshops, and scholarly initiatives. Its presence in Faenza—a city with centuries-old ceramic traditions—further cements its role as a guardian of both local craftsmanship and international ceramic excellence.

How would you describe the ‘Majolica Plate decorated with the coat of arms of the Medici of Florence,’ in the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza, Italy? When I visited the International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza on the 1st of April 2025, one piece that left a lasting impression on me was the Majolica Plate decorated with the coat of arms of the Medici of Florence. Though modest in size—just 12.3 cm in diameter—it stood out as a refined and powerful example of Renaissance ceramic artistry. Created between 1525 and 1530, the plate features the iconic Medici heraldry, beautifully rendered in vibrant tin-glaze colors that still hold their brilliance centuries later. What struck me most was the balance between its elegant simplicity and the rich symbolism it carried. The clean lines and careful proportions reflect the technical mastery of the Renaissance ceramic tradition, while the Medici emblem speaks volumes about the political and cultural reach of this powerful Florentine family. Standing before it, I felt a quiet awe—this small object encapsulated so much history, beauty, and meaning in such a graceful form.

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.metmuseum.org/met-publications/maiolica-italian-renaissance-ceramics-in-the-metropolitan-museum-of-art