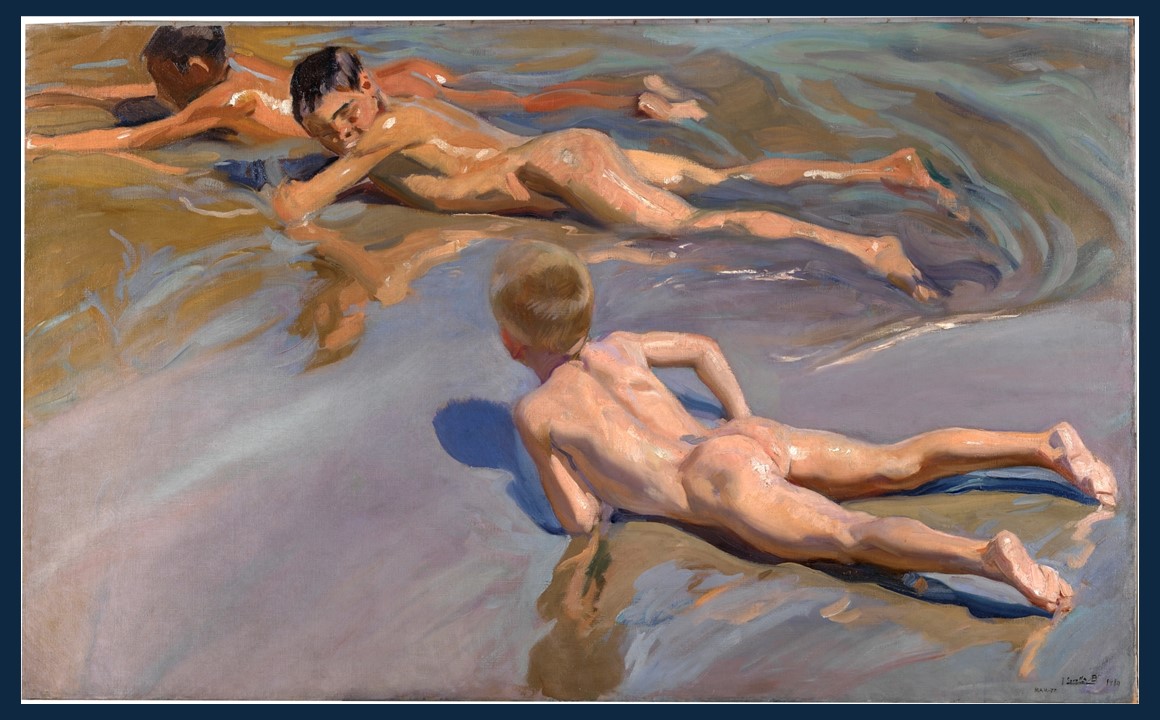

Boys on the Beach, 1909, Oil on Canvas, 118×185 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/boys-on-the-beach/edd7a202-c069-49f1-a3f4-eacf9b4022c2

‘Tis better to sit here beside the sea, / Here on the spray-kissed beach, / In silence, that between such friends as we / Is full of deepest speech. Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem, Silence, suggests an intimate communication transcending words. In contrast, the painting Boys on the Beach by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida is boisterous and joyfully noisy… capturing the perfect summer scene!

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida was born on February 27, 1863, in Valencia, Spain. He became an orphan at a young age and was raised by his aunt and uncle. Showing an early aptitude for art, he enrolled in the School of Fine Arts in Valencia at fifteen. Sorolla’s talent earned him scholarships to study in Madrid and later in Rome, where he absorbed the influences of classical and contemporary art. In 1888, he married Clotilde García del Castillo, who became his lifelong muse and the mother of his three children. Sorolla’s career flourished as he gained recognition for his vibrant, sunlit canvases, which captured the essence of Mediterranean life. His success extended internationally, with exhibitions in Paris, New York, and other major cities, solidifying his reputation as a master of light and colour.

The artist’s aesthetics were characterized by his masterful use of light and his vibrant, dynamic compositions. He is often associated with the Impressionist movement, although his style also incorporated elements of Realism and Luminism. Sorolla’s works frequently depicted scenes of everyday life, particularly those involving the sea, beaches, and people of his native Spain. His paintings are renowned for their brilliant use of colour, the fluidity of brushstrokes, and the ability to capture the fleeting effects of sunlight. Among his most famous works are The Bathing Hour, Sewing the Sail, and Walk on the Beach, which showcases his ability to render both the natural beauty and the human joy of his subjects. Sorolla’s accomplishments include numerous awards and honours, and his works continue to be celebrated and exhibited in prestigious museums around the world, including the Sorolla Museum in Madrid, which was once his home and studio.

Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida’s series of paintings featuring the children in the water motif is a vibrant celebration of childhood and the joy of seaside life. These works, created primarily during the early 20th century, depict boys playing at the seafront, capturing their carefree spirit and the shimmering beauty of the Mediterranean light. Sorolla’s masterful use of light and colour brings these scenes to life, emphasizing the translucence of water and the golden hues of sunlit skin. His loose, fluid brushstrokes convey movement and spontaneity, creating an almost impressionistic effect that captures fleeting moments of pure joy and innocence. Through these paintings, Sorolla not only showcases his technical brilliance but also his deep affection for the natural world and the simple pleasures of childhood.

The 1909 painting Boys on the Beach in the Prado Museum is probably Sorolla’s final example of his children in the water series. This work captures the essence of a carefree childhood with remarkable vibrancy. The painting depicts three nude boys playing at the sea’s edge, their bodies partially submerged in the sparkling blue water. Sorolla’s exceptional use of light and colour renders the scene with a radiant, sunlit quality, highlighting the reflections and ripples on the water’s surface. The boys’ skin glows with a sun-kissed warmth, contrasting with the cool tones of the sea. The artist’s fluid brushstrokes and dynamic composition convey a sense of movement and spontaneity as if the viewer is witnessing a fleeting moment of pure joy and freedom. The artist focuses on the children and the immediate foreground, creating an intimate and immersive experience. Through this painting, Sorolla masterfully captures the innocence and exuberance of childhood against the serene backdrop of the Mediterranean coast.

For a PowerPoint Presentation, titled At the Seafront, 13 Paintings by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/boys-on-the-beach/edd7a202-c069-49f1-a3f4-eacf9b4022c2 and https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/sorolla/what-you-need-to-know-about-sorolla