https://www.planetpompeii.com/it/map/casa-della-caccia-antica.html

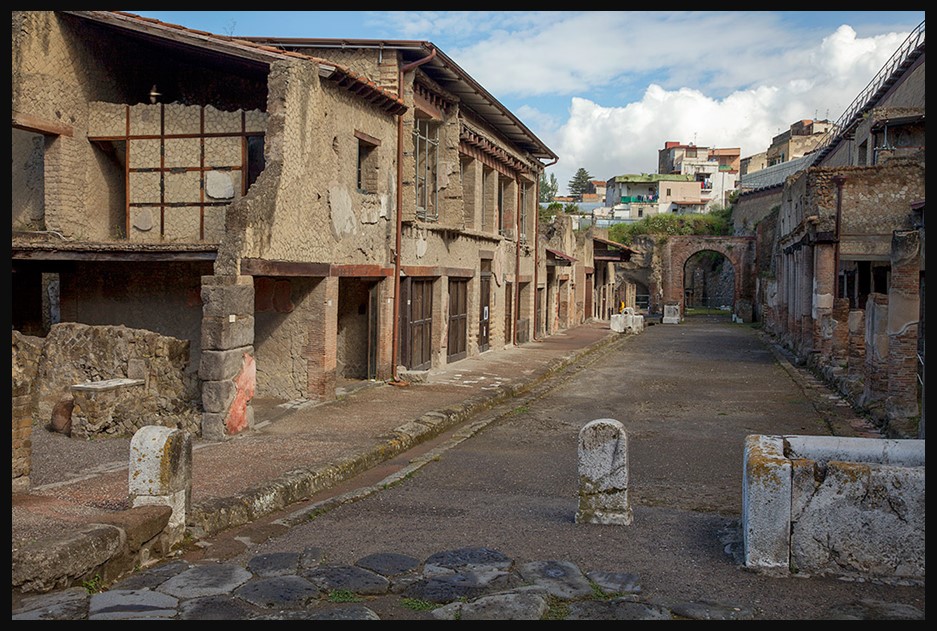

Nestled in the heart of Pompeii, the House of the Ancient Hunt (Casa della Caccia Antica) is a captivating glimpse into the artistry and domestic life of the ancient Roman elite. Named for its striking frescoes depicting dynamic hunting scenes, this modest yet elegant domus offers insight into the aesthetic tastes and daily routines of its former inhabitants. Unlike the grand villas of Pompeii’s wealthiest citizens, the House of the Ancient Hunt showcases a more intimate and functional design, yet it remains rich in decoration, reflecting the cultural fascination with nature and sport. As we step through its timeworn corridors, we uncover not just a beautifully preserved home, but a testament to the artistic mastery and lived experiences of a civilization frozen in time.

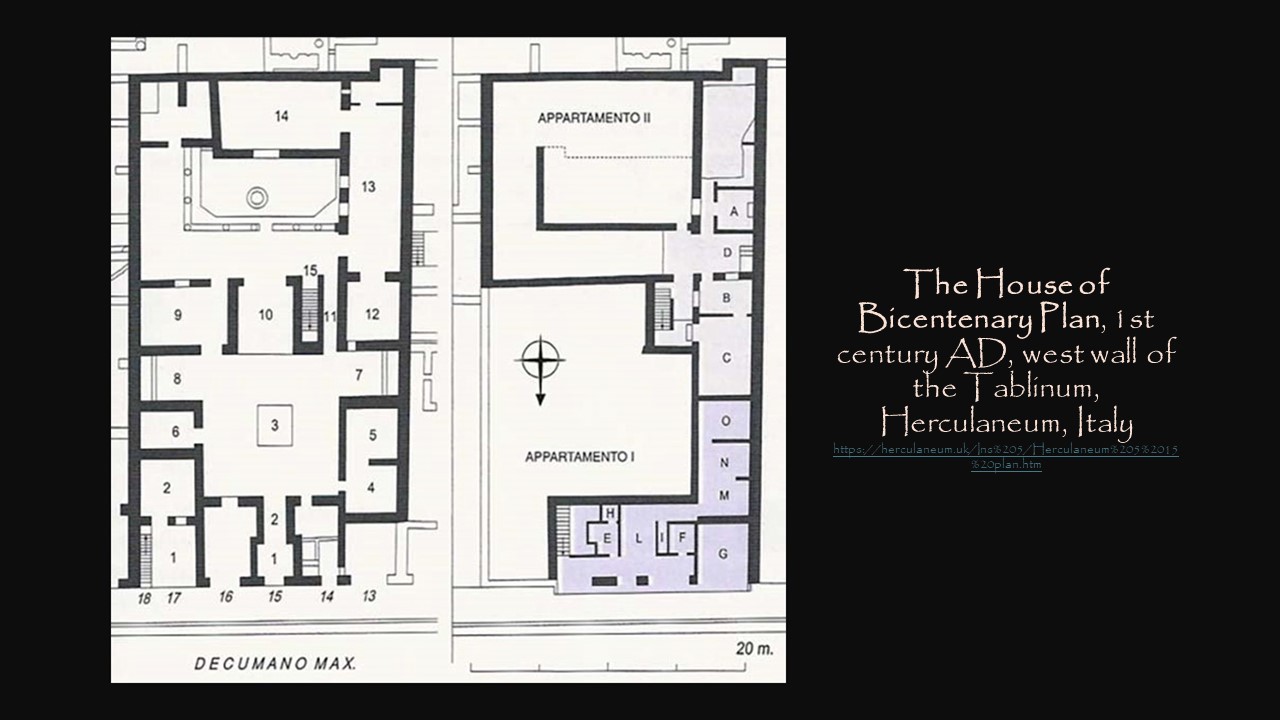

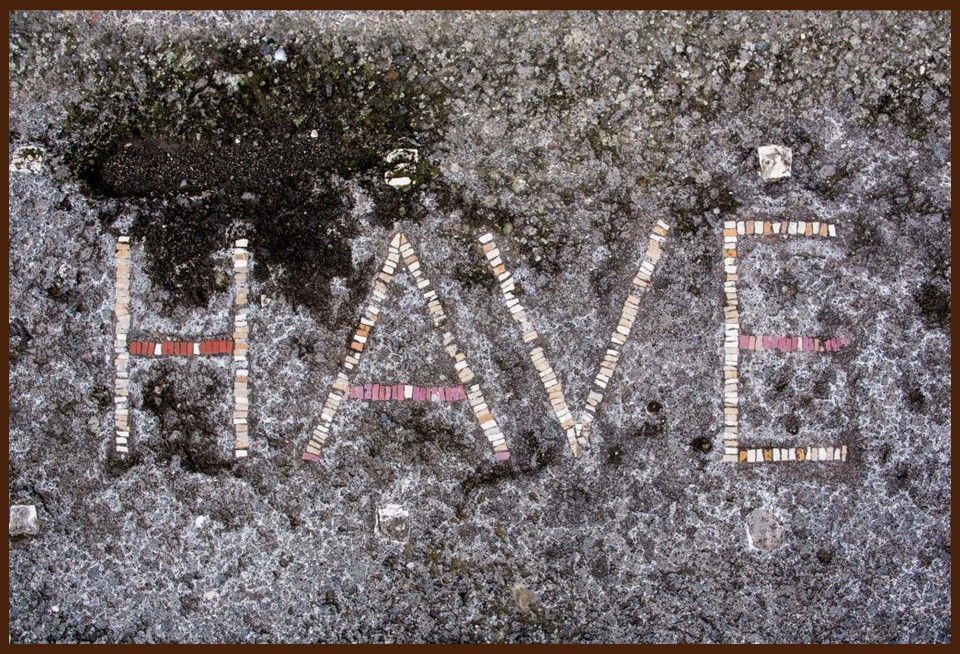

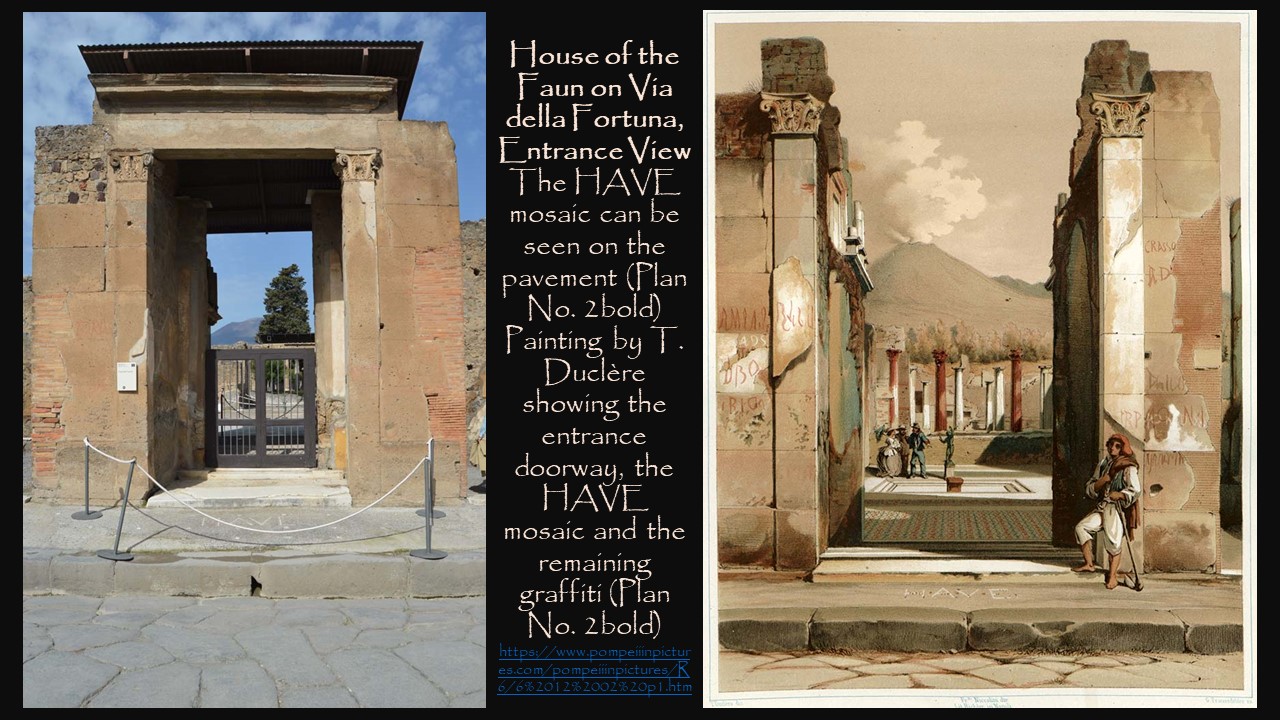

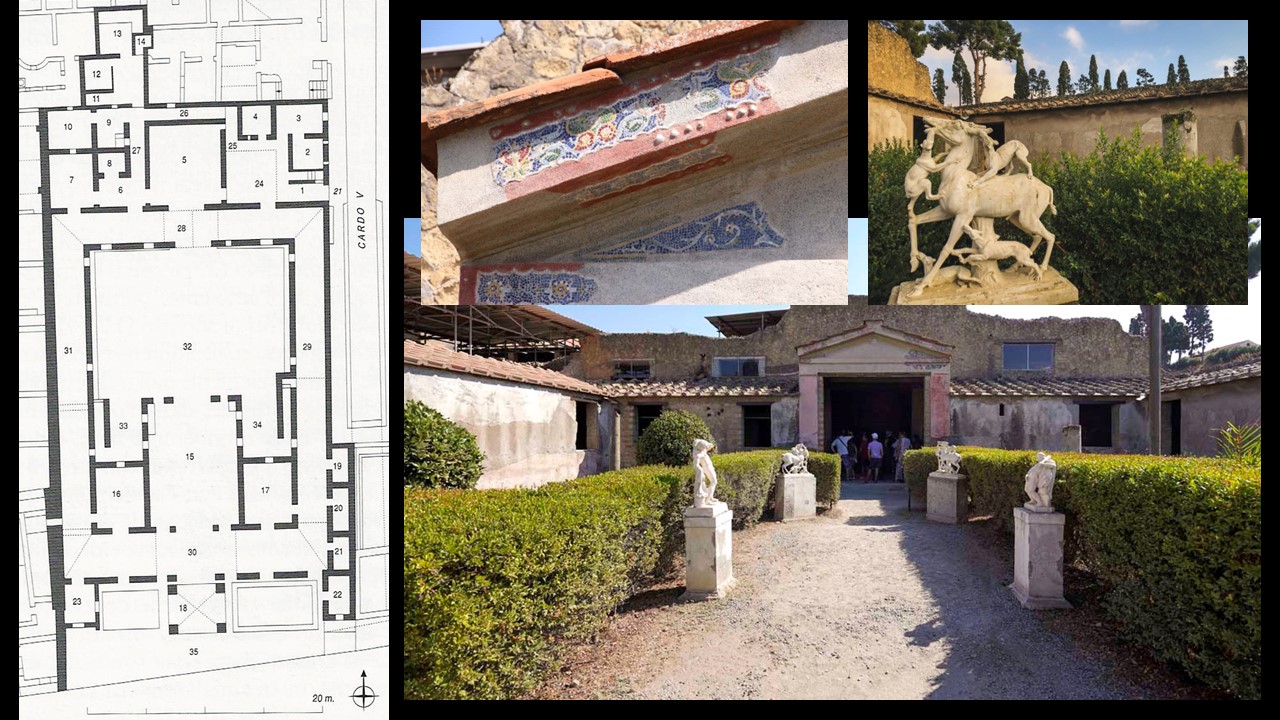

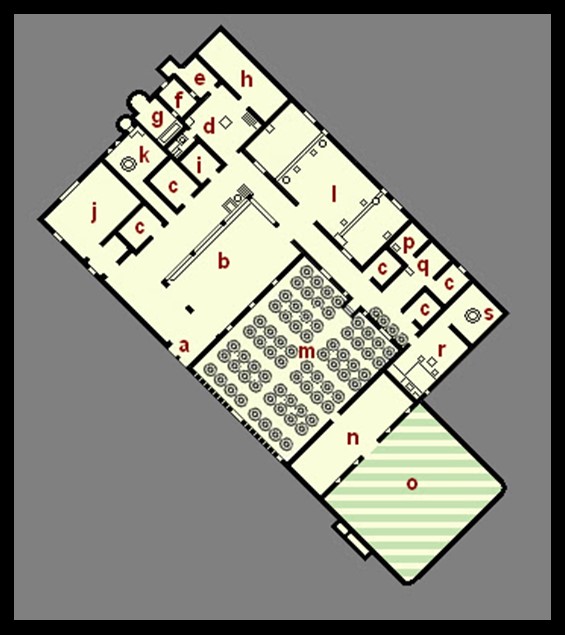

The House of the Ancient Hunt (Casa della Caccia Antica) is located on Via della Fortuna, in Regio VII, Insula 4, No. 48 within the city of Pompeii, near the Via degli Augustali, a central street that connected key areas of the city. Dating to the 2nd century BC, the house exemplifies a traditional Italic domus with a relatively compact yet elegant architectural plan. Upon entering, visitors pass through a narrow fauces (entrance corridor) that leads into a central atrium, which once featured an impluvium (a rainwater collection basin). Surrounding the atrium are several cubicula (bedrooms) and a tablinum (reception area), which opens into a charming peristyle garden adorned with frescoes. The house is best known for its vivid hunting-themed wall paintings, particularly in the peristyle, depicting dynamic scenes of hunters pursuing wild animals—a reflection of Roman aristocratic leisure and cultural ideals. Despite its relatively modest size compared to Pompeii’s grander residences, the House of the Ancient Hunt remains a fine example of domestic architecture, blending functionality with artistic refinement.

The tablinum of the House of the Ancient Hunt (Casa della Caccia Antica) served as the central reception area, positioned between the atrium and the peristyle, allowing for a seamless transition between the more public and private spaces of the house. This room, a hallmark of traditional Roman domus architecture, was likely used by the owner for conducting business, receiving guests, and displaying status through artistic decoration. In this case, the tablinum not only functioned as an administrative space but also as a visual gateway to the house’s most striking artistic feature – the vibrant frescoes that adorned the walls of this amazing house.

Tablinum in the House of the Ancient Hunt in Pompeii, 1886, Watercolour on Paper, 34.92x 47.94, Victoria and Albert Museum, London UK https://www.artrenewal.org/artworks/atrium-a-pompei-nella-domus-della-caccia-antica/luigi-bazzani/92235

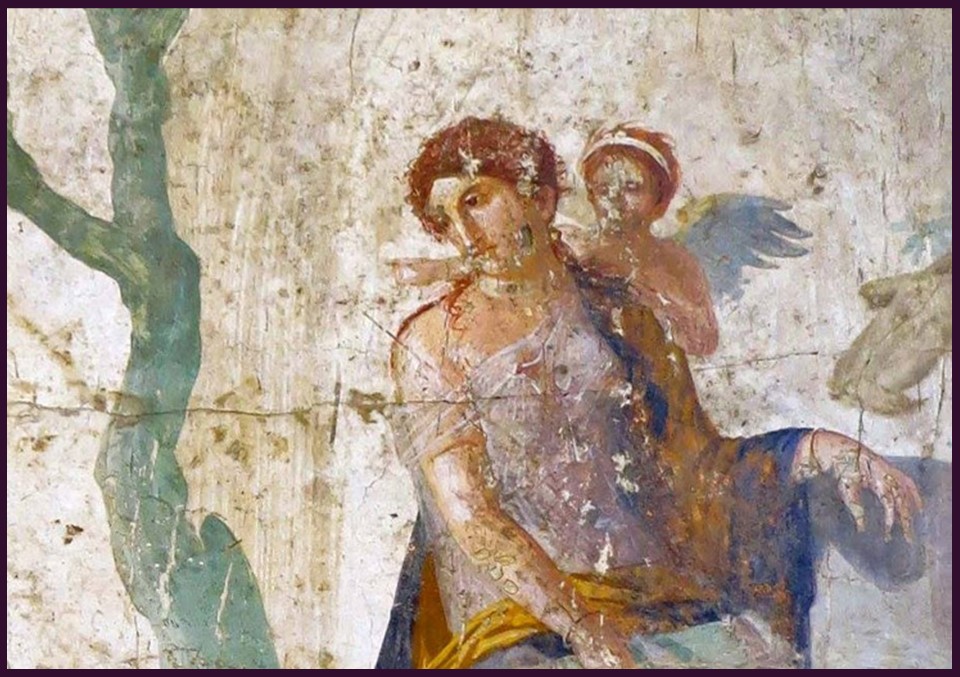

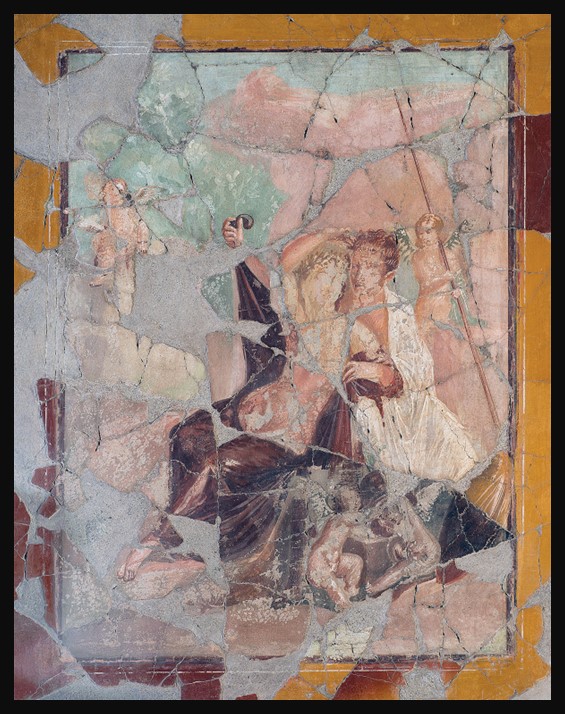

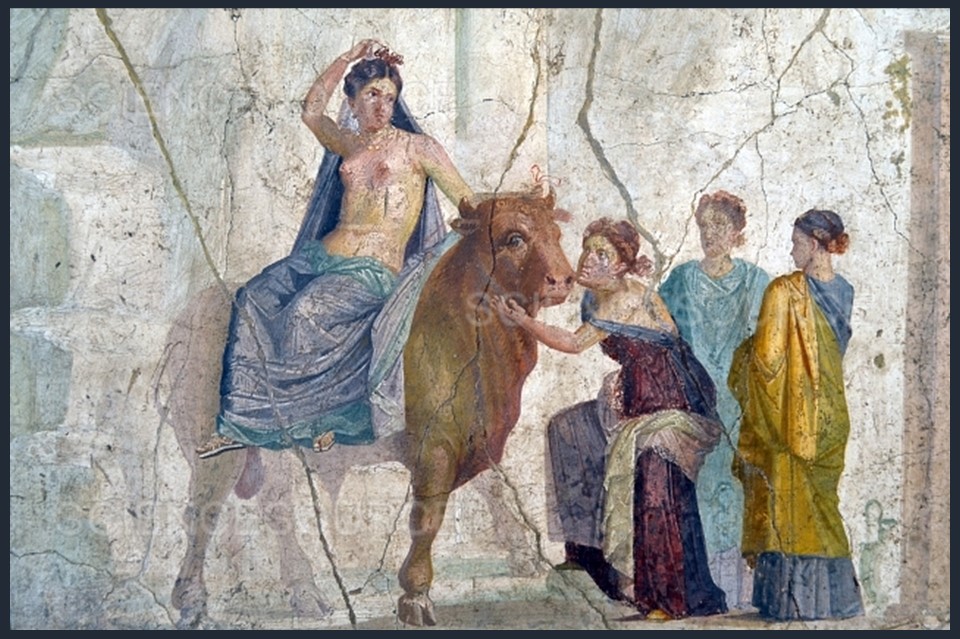

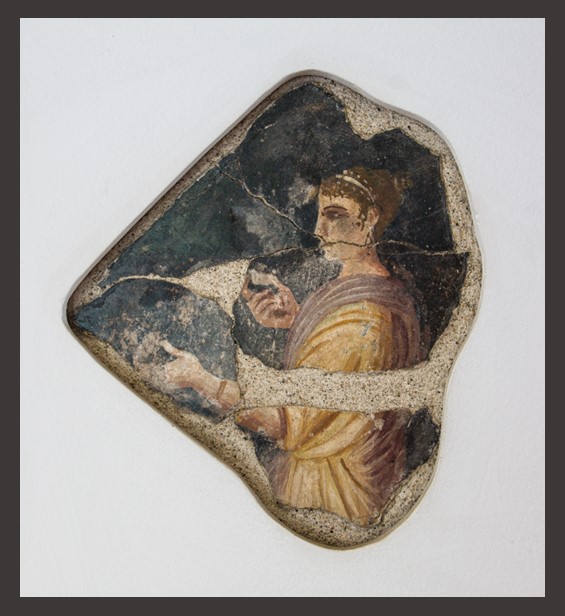

The room’s wall decoration follows the Fourth Pompeian Style (c. 60–79 AD), a highly theatrical and elaborate aesthetic that integrates architectural illusionism, intricate ornamentation, and mythological narratives. The lower portion of the walls features an imitation of polychrome marble cladding, reflecting a taste for luxury by simulating the expensive materials used in elite Roman homes. The central register is striking, set against a turquoise blue background, divided into panels adorned with winged figures, architectural views on a white background, and predellas depicting cupids engaged in hunting, reinforcing the house’s thematic connection to the chase. Two prominent mythological scenes stand out: Theseus and Ariadne outside the labyrinth, symbolizing triumph and abandonment, and Daedalus presenting Pasiphae with the wooden bull, an episode tied to deception and desire in the myth of the Minotaur’s conception.

Aesthetically, the decoration of the Tablinum exemplifies the Fourth Style’s emphasis on illusionistic depth, vibrant color contrasts, and dynamic compositions. The turquoise blue central background, a rare and striking choice, enhances the ethereal quality of the winged figures while simultaneously creating a vivid contrast with the architectural elements. The mythological vignettes, rendered in delicate, miniature-like detail, evoke a refined taste for storytelling, drawing the viewer into dramatic moments from Greek mythology. The cupids hunting in the predellas serve as a playful yet symbolic nod to the themes of pursuit and conquest, which resonate both in the act of hunting and in the mythological narratives depicted above. The upper zone, with its white background and fantastical architectural motifs, further extends the illusionistic space, creating a sense of openness and grandeur. This interplay of myth, ornamentation, and spatial illusion not only enhances the aesthetic richness of the room but also reflects the intellectual and artistic ambitions of its owner, transforming the Tablinum into a theatrical stage of myth, power, and beauty.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of the House of the Ancient Hunt in Pompeii, please check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.planetpompeii.com/it/map/casa-della-caccia-antica.html and https://pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/R7/7%2004%2048%20p1.htm