https://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/file.php/ARCH396/Didaktiko%20yliko/PanKal997.htm

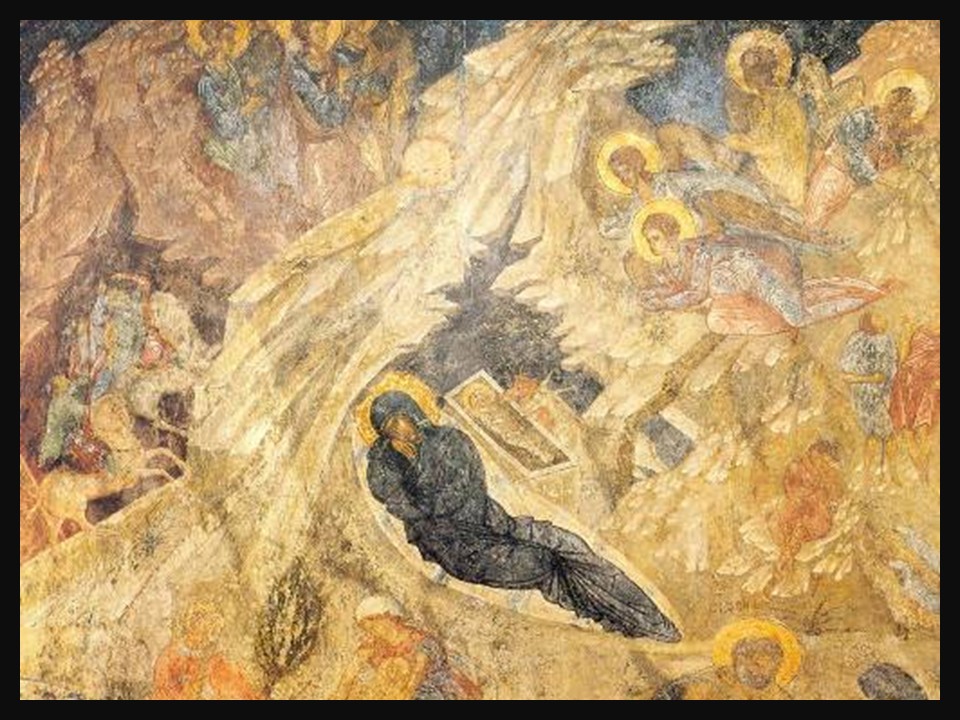

The Nativity Fresco of Peribleptos Monastery in Mystras captures the spiritual heart of the season through the radiant artistry of Byzantine devotion. High on the slopes of Mistra, within the Monastery of Perivleptos, the Nativity scene painted across its frescoed walls unfolds as a vivid testament to Byzantine spirituality and artistic mastery. Created in the 14th century, this depiction of Christ’s birth captures both the human tenderness and divine mystery central to Orthodox faith. Beneath the soft light filtering through the dome windows, figures of Mary, Joseph, angels, and shepherds converge around the newborn Christ, embodying a theology of incarnation rendered through luminous color and sacred geometry. As we celebrate Christmas Day 2025, this fresco invites reflection on how art can transform stone and pigment into a living proclamation of hope and transcendence.

Mystras and the Late Byzantine World

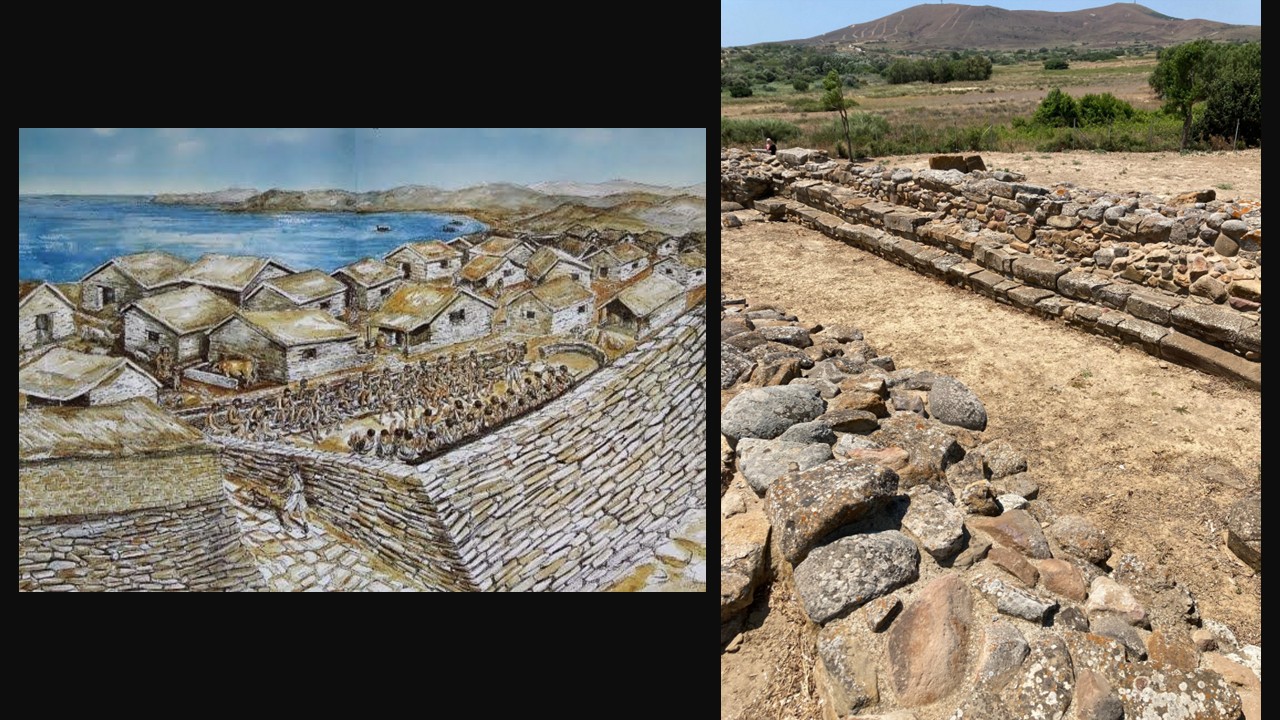

Mystras, located near ancient Sparta in the Peloponnese, was one of the most significant centers of the late Byzantine Empire, flourishing between the 13th and 15th centuries. Established by the Franks in 1249 and later reclaimed by the Byzantines, it became the capital of the Despotate of the Morea, a major political, intellectual, and artistic hub during Byzantium’s final centuries. The city’s fortified acropolis, palaces, monasteries, and churches, including the Peribleptos, Pantanassa, and Hodegetria to mention just three, reveal a remarkable synthesis of political power and cultural refinement. Mystras nurtured a vibrant artistic school known for its refined frescoes and architecture, which combined classical Byzantine traditions with new stylistic developments that prefigured aspects of the Renaissance. Today, Mystras stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, representing the last brilliant flowering of Byzantine art and spirituality before the empire’s fall.

https://www.religiousgreece.gr/en/attractions/monastery-perivleptos

Late Byzantine Frescoes of Peribleptos

Among its most notable monuments, the Katholikon (main church) of the Peribleptos (Perivleptos) Monastery was founded in the mid-14th century, most scholars attribute its patronage to the first Despot of the Morea, Manuel Kantakouzenos, and his wife Isabella (Isabelle) de Lusignan. Built into the southeast slope of the town and partly supported by a cave, the church is a two-column cross-in-square plan that exemplifies the local “Mystras style,” with squared stone and inlaid tilework that give the exterior a fortress-like appearance. Its dating is commonly placed around the 1350s–1370s, when Mystras was a lively cultural and political center of the late Byzantine Peloponnese.

The interior is celebrated for an extensive and unusually well-preserved cycle of late Byzantine frescoes (mid-14th century) that focus especially on the life of the Virgin and key Gospel scenes, paintings that art historians link stylistically to Cretan and Macedonian workshops and that show Palaeologan-era innovations in space and movement. Because these frescoes survive largely in situ, the Peribleptos Katholikon is considered crucial for understanding late Byzantine painting and the artistic renaissance in the Morea; the whole site of Mystras is protected for its outstanding medieval ensembles.

https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/peribleptos-mystras

The Nativity Fresco at Peribleptos

The Nativity scene in the Peribleptos Monastery at Mystra stands as one of the most evocative frescoes of the late Byzantine period, part of the church’s rich Christological cycle. Depicted with serene grace and otherworldly poise, the Virgin reclines beside the Christ Child in a rocky grotto, encircled by Joseph, the Magi, shepherds, and angels—each slender figure animated by elegant gestures and expressive faces. The artist achieves a vivid harmony of color and form, combining traditional Byzantine iconography with a confident, freer sense of spatial rhythm. The layered landscape, luminous tones, and effortless authority of each depiction reveal the maturity of the Mystras school, whose refinement would profoundly influence the later Cretan School of icon painters.

Aesthetically, the Nativity fresco exemplifies the serene elegance and emotional subtlety of late Byzantine art at its height. The soft modulation of color—from deep blues and warm ochres to pale rose and gold—infuses the composition with both tenderness and transcendence. Figures are modeled with a supple handling of light and shadow that departs from earlier rigidity, achieving a lyrical balance between solemnity and grace. This confident, almost Renaissance sensibility anticipates the stylistic currents that would flow from Mystras to Crete and, ultimately, to Venice. Through this luminous synthesis of theology and beauty, the Peribleptos Nativity becomes not merely a devotional image but a harbinger of artistic renewal across the Mediterranean world.

As we celebrate Christmas Day 2025, the Nativity fresco at Peribleptos reminds us that the story of Christ’s birth continues to inspire wonder, devotion, and artistic creation across the centuries. Just as the figures in the fresco gather around the newborn Savior, we too are invited to pause, reflect, and share in the warmth, hope, and light that this holy day brings. In the quiet glow of candlelight or the brilliance of a winter sunrise, the spirit of Mystra endures, connecting past and present in a timeless celebration of faith and beauty.

Explore further: Download our PowerPoint Presentation on the Byzantine Monuments of Mystras for educators, students, and art lovers… HERE!

Bibliography: analysed in detail by The Byzantine Legacy: https://churchesingreece.blogspot.com/2014/07/mystras-peribleptos.html and in Greek https://www.ime.gr/choros/mystras/gr/E/14E/14E12.html