Sketchbook by Hans Liska, 1942-43, published in 2 albums by the house of Carl Werner in Reichenbach, and sponsored by Junkers Flugzeug und Motorenwerke AG, with sketches and colour illustrations by the artist

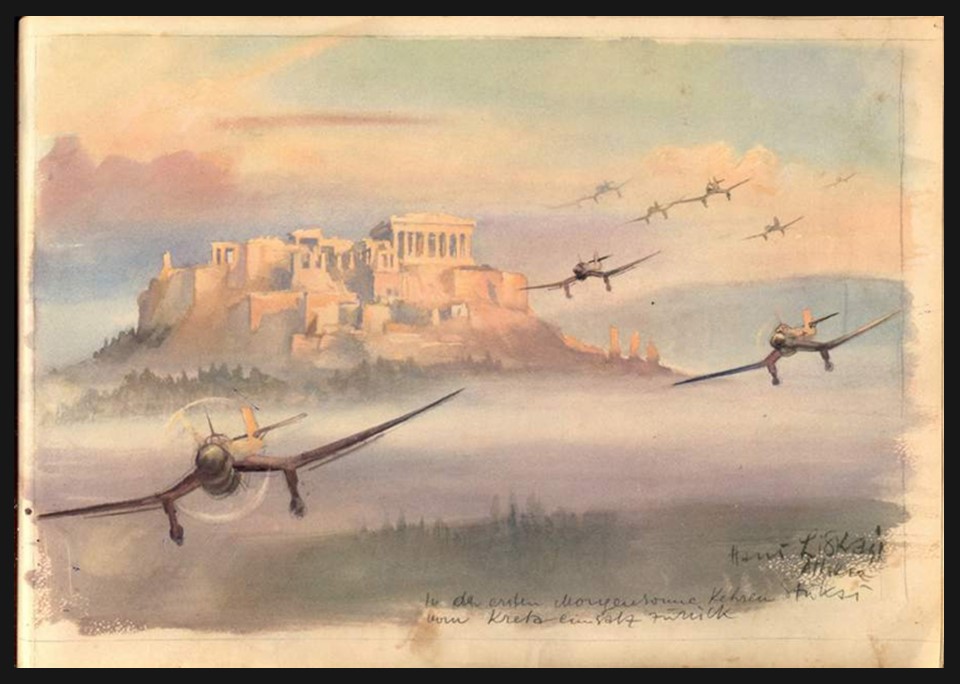

Stukas returning from their mission at Crete in the first light of the rising sun, the Parthenon in the background, 1942-43, circa 20×30 cm, Private Collection

https://www.allworldwars.com/World%20War%20II%20Sketches%20By%20Hans%20Liska.html

Hans Liska’s watercolour ‘Stukas Returning from Their Mission at Crete in the First Light of the Rising Sun, the Parthenon in the Background’ exemplifies his role as a German WWII propaganda artist, combining the grandeur of ancient Greece with the military might of German Stuka bombers. The painting portrays the planes soaring past the Parthenon at dawn, symbolizing both cultural heritage and wartime power. Yet, while the Stukas embody fleeting military force, the Parthenon stands as a timeless monument to ideals of culture, democracy, and human creativity – qualities that far outlast the shadows of war. Is the scene effectively captured in my Haiku poem… ‘Morning sun ascends, / Stukas soar past Parthenon stones, / Shadows brush the sky…’

Hans Liska (1907–1983) was a highly regarded Austrian artist and illustrator, recognized for his exceptional ability to depict dynamic scenes with meticulous detail. Born in Vienna, he studied at the prestigious Akademie der bildenden Künste, where he developed a solid foundation in classical art techniques, including the use of line, shading, and perspective. Early in his career, Liska worked as a commercial illustrator, contributing to various advertising campaigns and publications. His early illustrations reflected a keen understanding of movement and energy, which would later become central themes in his most famous works. His versatility as an artist allowed him to master both static compositions and those bursting with action, making him an ideal fit for the fast-paced and visually compelling world of commercial art.

During World War II, Liska’s talents were recognized by the German military, and he was appointed as an official war artist for the Wehrmacht. In this role, he was deployed to various battlefronts, where he sketched and painted vivid scenes of combat and military life. His wartime work captured the intensity of battle, portraying soldiers in dramatic, often heroic, poses. Many of these illustrations were published in Nazi propaganda outlets such as Signal, a widely circulated military magazine. These works were intended to glorify the German war effort and morale, making them powerful tools of propaganda. Despite the ideological connotations of these illustrations, they remain a testament to Liska’s technical skill in conveying motion, emotion, and atmosphere in his art. His ability to illustrate human experiences during the war made him an important figure among World War II artists, though his works were often politically charged.

After the war, Liska successfully transitioned to the commercial sphere, distancing himself from his wartime associations. He became particularly renowned for his work with Mercedes-Benz, for whom he produced numerous illustrations and advertisements. His post-war art retained the fluid lines, dramatic contrasts, and sense of movement that characterized his earlier works, but now applied to more peaceful subjects, such as travel, high-end automobiles, and urban life. Liska’s skill in depicting speed and elegance made his automotive illustrations iconic within the advertising industry. Over time, his work became widely admired by both art collectors and automotive enthusiasts, cementing his legacy as one of the leading commercial illustrators of the 20th century. Today, Liska’s illustrations are valued not only for their artistic quality but also as historical artefacts that reflect the cultural and industrial landscape of mid-20th century Europe.

For a PowerPoint Presentation inspired by Hans Liska’s watercolour Stukas returning from their mission at Crete, please… Check HERE!