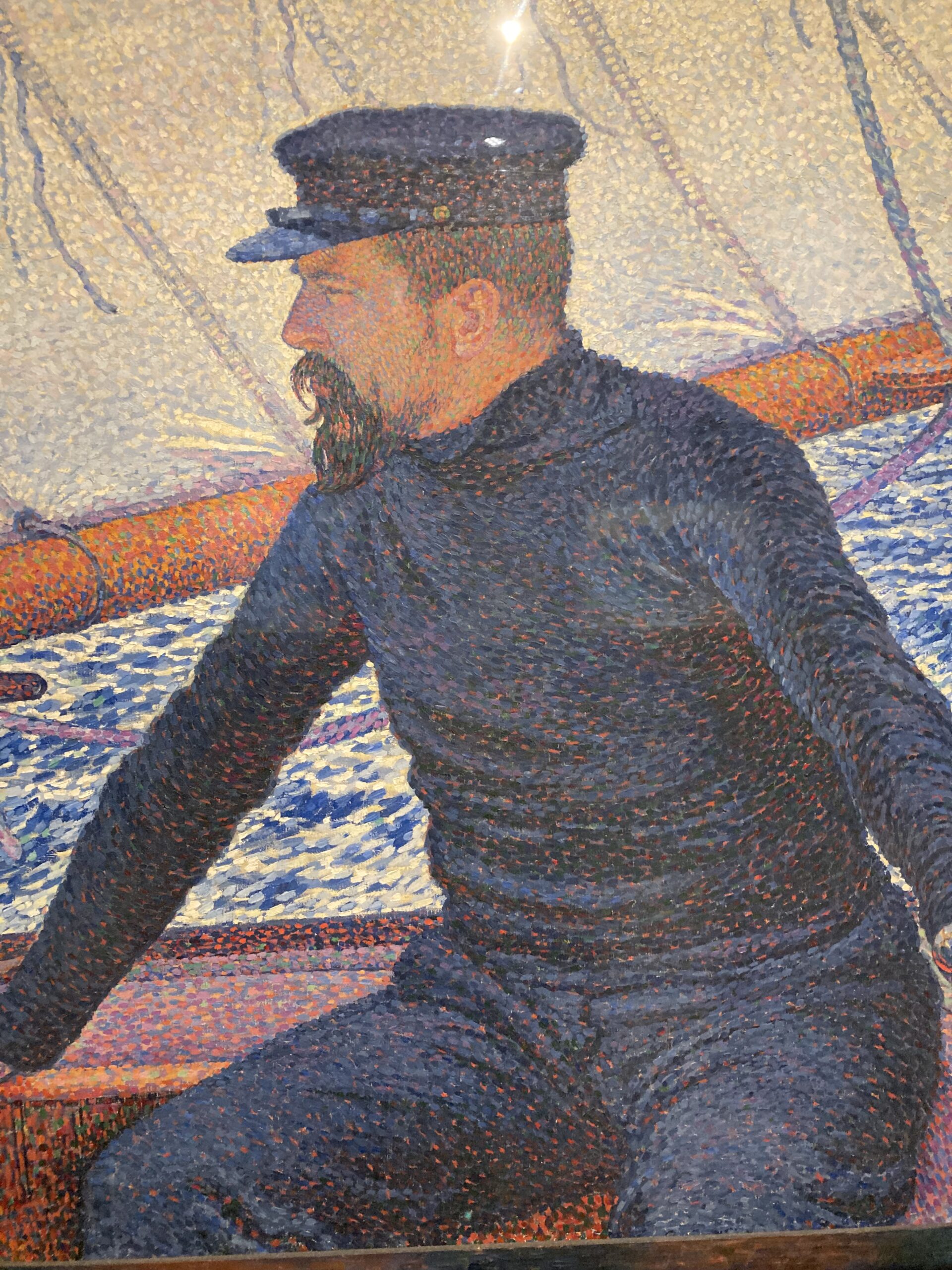

Venice, the Yellow Sail, 1904, Oil on Canvas, 73×92 cm, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France (In deposit to the Museum of Fine Arts and Archeology of Besançon since 1972) – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean Exhibition (10.01 – 07.04.2024), February 2024

The Exhibition Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean (1891-1914) was held in Athens at the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation. This event was organized in collaboration with several prominent European museums and institutions, including the Musée d’Orsay, the National Gallery in London, the Centre Pompidou, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Besançon, the Musée de l’Annonciade, the Musée de Grenoble, the Musée national d’archéologie, d’histoire et d’art – Luxembourg, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, as well as various European private collectors. The exhibition showcased works by renowned artists such as Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, Théo van Rysselberghe, Henri Matisse, Henri Manguin, and Louis Valtat, many of which were being displayed in Greece for the first time. One piece that particularly, captivated me was Paul Signac’s 1904 painting, Venice, the Yellow Sail.

Let’s explore the Exhibition ‘Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean’ through Paul Signac’s painting, Venice, the Yellow Sail, by posing questions about When, How, What, and Who…

How would you define Neo-Impressionism? Neo-Impressionism is an art movement that emerged in the late 19th century as a reaction to the spontaneity and subjectivity of Impressionism. It is characterized by a systematic and scientific approach to painting, primarily focusing on the use of colour and light. Neo-Impressionists employed techniques such as Pointillism or Divisionism, where small dots or strokes of pure colour are applied to the canvas. When viewed from a distance, these dots visually blend to create vibrant, luminous compositions. The movement was led by artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who sought to bring a greater sense of order and structure to their works through meticulous planning and an emphasis on colour theory.

What is Pointillism or Divisionism? Divisionism or Pointillism is a painting technique developed by Neo-Impressionist artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac in the late 19th century. This method, which sought to establish a scientific foundation for the Impressionist exploration of light and colour, involves applying small, distinct dots of pure colour to a canvas, which blend visually in the viewer’s eye to create a cohesive image with enhanced vibrancy and luminosity. Inspired by M-E Chevreul’s 1839 colour theory on simultaneous contrast, aimed to enhance luminosity, as optically mixed colours tend toward white, the technique significantly influenced French painters, especially among the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Neo-Impressionists.

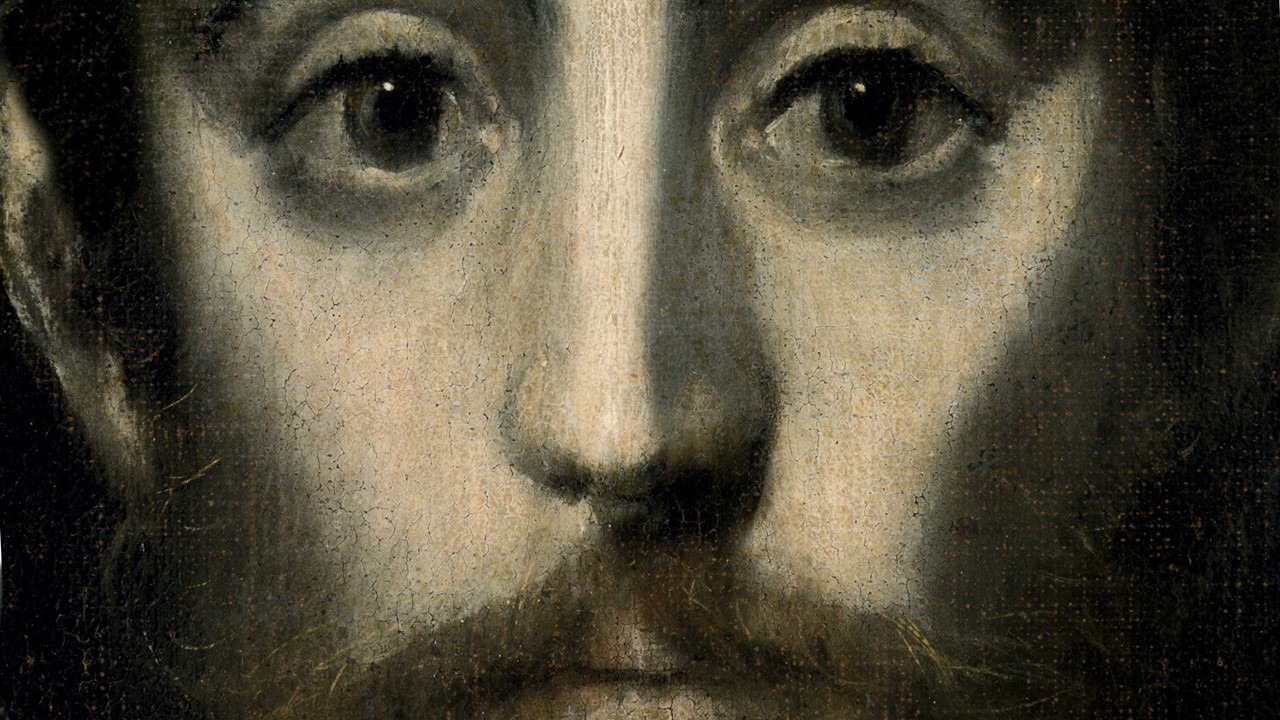

Portrait of Paul Signac at the helm of the Olympia (detail), 1896, Oil on Canvas, 93×114 cm, Private Collection – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean Exhibition (10.01 – 07.04.2024), February 2024

Who is Paul Signac? Paul Signac was a French Neo-Impressionist painter renowned for pioneering the Pointillist technique alongside Georges Seurat. Born in Paris, Signac initially trained as an architect before dedicating himself to painting. Influenced by Impressionism, he soon embraced a more scientific approach to colour and light, leading to his collaboration with Seurat to develop Divisionism. Signac travelled extensively, drawing inspiration from the Mediterranean and its vivid landscapes. His works often depicted harbours and coastal scenes, capturing the interplay of light and water. In addition to his artistic contributions, Signac authored several important texts on art theory, including From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, which articulated the principles of Neo-Impressionism. His legacy endures through his innovative techniques and his role in shaping modern art.

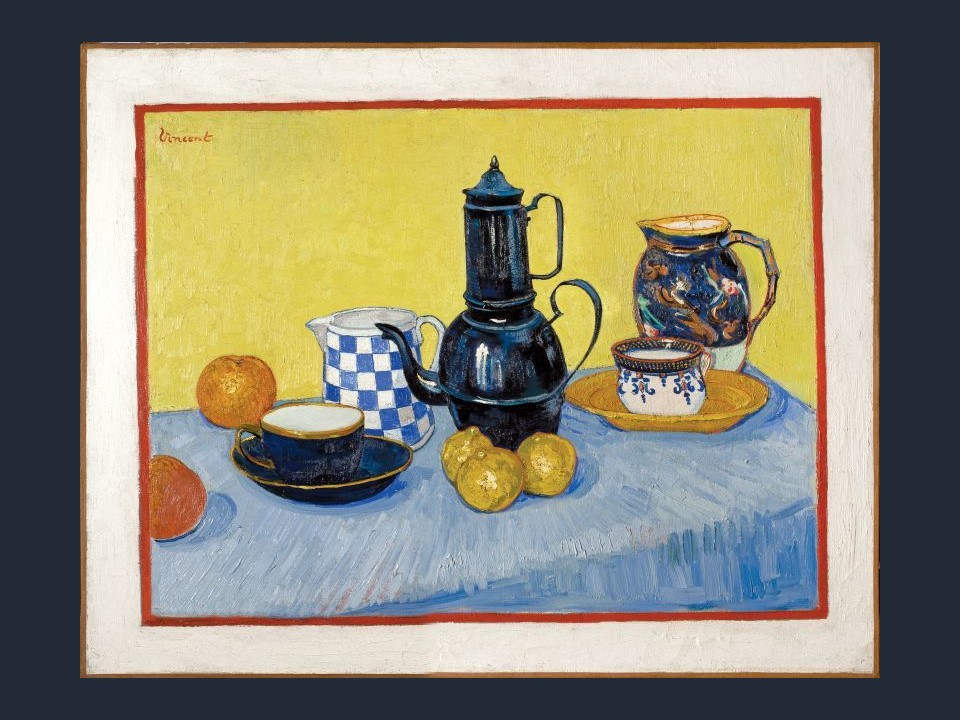

How would Signac’s painting Venice, the Yellow Sail be described? Paul Signac’s painting Venice, the Yellow Sail, housed in the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, is a vibrant and luminous depiction of Venice’s iconic waterways. The focal point is a sailboat with a striking yellow sail, which stands out against the intricate interplay of blues and greens in the water and sky. Signac captures the essence of Venice with a keen eye for the effects of light and colour, imbuing the scene with a sense of movement and radiance. The painting reflects Signac’s love for sailing, his fascination with maritime subjects and his mastery of Divisionism, resulting in a visually captivating representation of Venice’s beauty.

When did Paul Signac visit Venice? The artist visited Venice for the first time in the spring of 1904. Initially planning to visit in the summer of 1903, Signac’s fascination with the city, partly influenced by John Ruskin’s “The Stones of Venice,” led him to postpone his travels until the following year. Arriving at the end of March 1904, he stayed until late May, producing a significant number of watercolours during his visit. The oils he created were exhibited at the 1905 Salon des Indépendants, where they garnered praise from both the public and critics. Louis Vauxcelles, for example, remarked… nothing is more vibrant, more atmospheric, than the shimmering Venice of M. Signac.

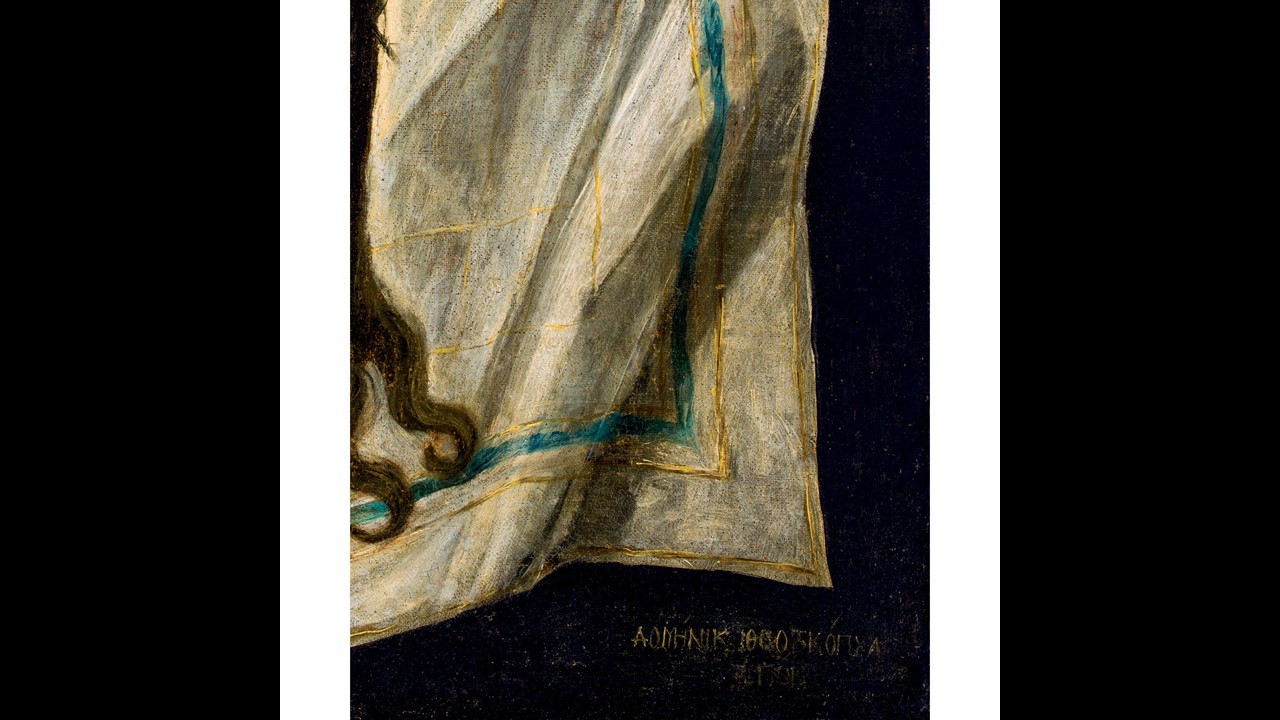

Venice, the Yellow Sail (detail), 1904, Oil on Canvas, 73×92 cm, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France (In deposit to the Museum of Fine Arts and Archeology of Besançon since 1972) – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, Neo-Impressionism in the Colours of the Mediterranean Exhibition (10.01 – 07.04.2024), February 2024

How is Louis Vauxcelles’s remark nothing is more vibrant, more atmospheric, than the shimmering Venice of M. Signac applied to Signac’s painting Venice, the Yellow Sail? In Signac’s painting Venice, the Yellow Sail, Signac captures the essence of Venice’s shimmering beauty with remarkable vibrancy and atmosphere. The painting radiates with the luminous colours of the city’s water canals and buildings, soft and hazy pinks, lilacs, and greens, evoking the play of light and shadow characteristic of Venice. The focal point of the yellow sail adds a dynamic burst of colour against the serene backdrop, further enhancing the painting’s vibrancy. Signac’s meticulous use of Divisionism infuses the scene with an ethereal quality, as the carefully placed dots of colour blend harmoniously to create a captivating and immersive depiction of Venice’s unique atmosphere.

For a PowerPoint on Paul Signac, please… Check HERE!