Education in Byzantium was a complex system deeply rooted in the traditions of the Greco-Roman world and the Christian Church, evolving over the centuries to reflect the socio-political and religious changes within the empire. This system spanned from the establishment of Constantinople in 330 AD to the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 AD. It was significantly influenced by classical Greek education, Roman administrative needs, and Christian teachings, creating a unique blend of classical and ecclesiastical learning.

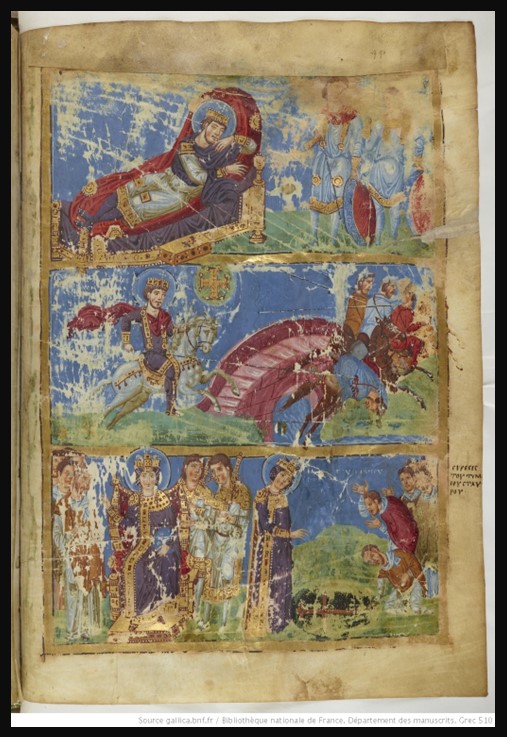

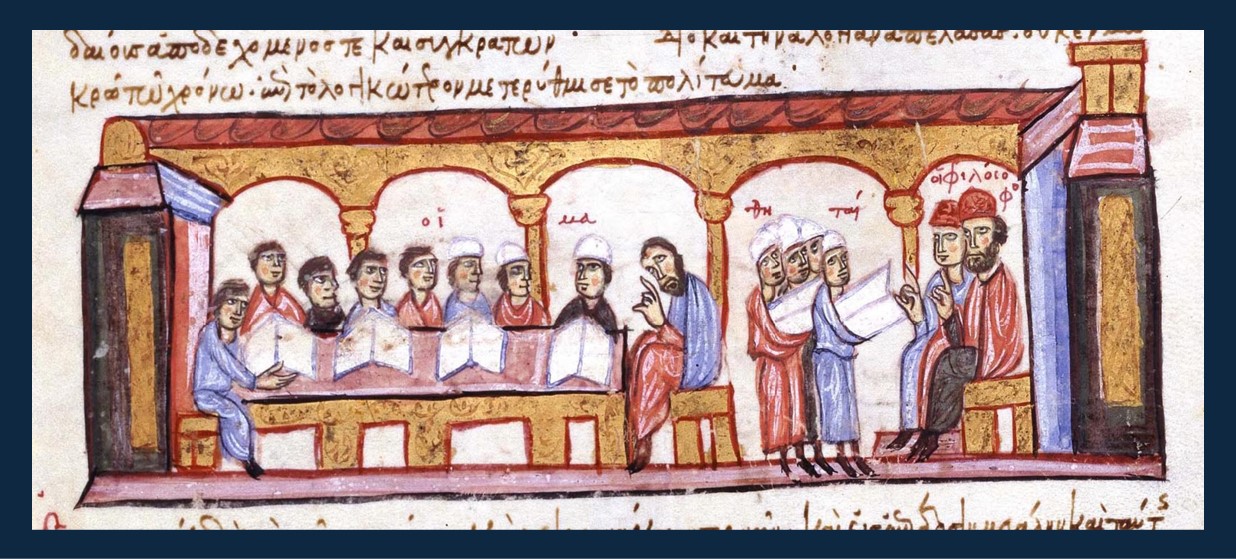

Miniature 134r in the illuminated manuscript Madrid Skylitzes presents a Byzantine classroom. Using the illumination as an example, let’s explore… school reality 1.000 years ago!

The Madrid Skylitzes is a richly illustrated manuscript, the only known illuminated manuscript of a Byzantine Greek Chronicle, that serves as a vital historical record of the Byzantine Empire from the reign of Emperor Nikephoros I in 811 AD to the death of Emperor Michael IV in 1057 AD. Named after the Spanish city where it is currently housed, the manuscript is based on the work of John Skylitzes, a late 11th century historian. The Madrid Skylitzes is notable for its detailed and vivid miniatures, 575 of which combine Byzantine, Western and Islamic elements of unparalleled significance for art historians. These miniatures depict the period’s significant events, battles, and personalities, providing a unique visual accompaniment to the textual narrative. This manuscript is one of the few surviving examples of Byzantine historical illustration and is invaluable for its insights into Byzantine art, culture, and historical scholarship.

Miniature 134r of the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript vividly illustrates the essence of education during the Byzantine era, particularly the progress of letters during the reign of Constantine Porphyrogenitus (913-959). On the left side of the miniature, a group of eight male students is shown seated at a desk with open notebooks, highlighting their active participation in learning, presided over by their teacher, who expounds and explains with an upraised hand. Further to the right, four (possibly six) more students with notebooks in hand are depicted standing before two professors of philosophy. The scene takes place in a well-constructed, rectangular building that is collonaded, spacious, and well-furnished. The students appear young and attentively engaged. Their expressions, postures, and gestures suggest concentration and eagerness to absorb the teachings. The three teachers, two of whom are bearded, are shown with upraised pointer fingers, clearly in the process of delivering a lesson. Overall, the scene conveys a sense of disciplined yet dynamic learning, reflecting the structured and vibrant nature of Byzantine scholarly life. The attention to detail in the students’ attentive postures and the teachers’ engaged gestures underscores the era’s commitment to education and intellectual growth. https://www.academia.edu/31545633

John Skylitzes, emphasizing Emperor Constantine’s praiseworthy and wondrous qualities, highlights his interest in education and explains that …On his own initiative, the Emperor brought about a restoration of the sciences of arithmetic, music, astronomy, geometry in two and three dimensions and, superior to them all, philosophy, all sciences which had for a long time been neglected on account of a lack of care and learning in those [238] who held the reins of government. He sought out the most excellent and proven scholars in each discipline and, when he found them, appointed them teachers, approving of and applauding those who studied diligently. Hence he put ignorance and vulgarity to flight in short order and aligned the state on a more intellectual course.

Education in the Byzantine Empire was generally accessible to the upper and middle classes, while the lower classes had limited access due to economic constraints. The system was predominantly male-oriented, but there are records of women receiving education, particularly within monastic settings or among wealthy families. Notable figures in Byzantine education included Photius, a leading intellectual and Patriarch of Constantinople in the 9th century, and Michael Psellos, an 11th-century scholar who contributed significantly to philosophy, history, and rhetoric.

The legacy of Byzantine education is significant, particularly in its role in preserving and transmitting classical Greek and Roman knowledge to the Islamic world and later to Western Europe during the Renaissance. This educational system influenced Islamic education during the Abbasid Caliphate and contributed to the revival of learning in Western Europe. Through its sophisticated blend of classical and Christian teachings, Byzantine education formed a crucial bridge between the ancient world and medieval Europe, shaping intellectual traditions in both the Eastern and Western worlds.

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.academia.edu/31545633 and https://www.persee.fr/doc/scrip_0036-9772_2007_num_61_2_4229 and https://www.bne.es/sites/default/files/redBNE/Actividades/Exposiciones/2024/skylitzes-matritensis-bne-en.pdf