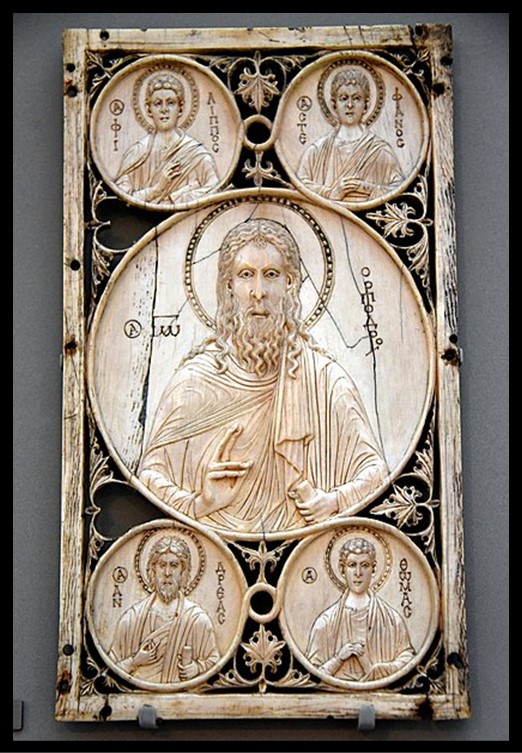

the_Baptist_and_saints,_c._1000_CE._

Ivory_with_traces_of_gilding._From_Constantinople,_Byzantine_

Empire_%28Istanbul,_Turkey%29._Victoria_and_Albert_Museum.jpg

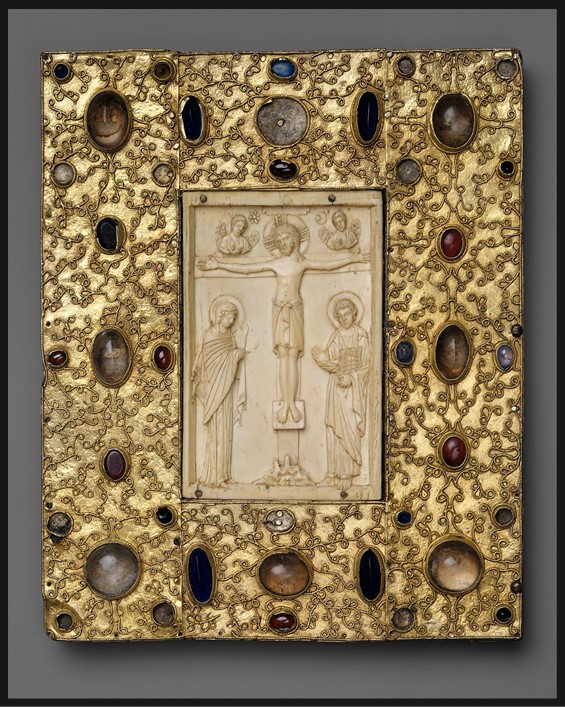

On the 7th of January, the Feast Day of Saint John the Baptist, the Greek Orthodox Church celebrates a significant figure in Christian tradition. His Apolytikio is a testimony to his elevated status… ‘The memory of the just is celebrated with hymns of praise, but the Lord’s testimony is sufficient for thee, O Forerunner; for thou hast proved to be truly even more venerable than the Prophets, since thou was granted to baptize in the running waters Him Whom they proclaimed.’ The Ivory Plaque of St John the Baptist and Four Saints in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is evidence of his importance in the arts.

This Byzantine ivory plaque, housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum, presents a commanding depiction of Saint John the Baptist surrounded by four saints in a beautifully carved composition. St. John, central to the piece, gazes solemnly outward, his right hand raised in a gesture of blessing reminiscent of the iconic Christ Pantocrator. He holds a scroll, in his left hand, a symbol of prophetic wisdom. Encircling him in a design formed by an elegant tubular vine are busts of Saints Philip and Stephen above and Saints Andrew and Thomas below, creating a balanced visual symmetry.

The surface between these circular frames is filled with intricate, pierced foliage, a testament to the Byzantine craftsman’s skill. Traces of gilding and remnants of red-tinted inscriptions hint at the plaque’s former vibrancy, once illuminated with a regal gold shine and rich colours highlighting each saint’s name. The eyes of the figures, enhanced with glass paste beads, lend a lifelike intensity, particularly in St. Philip, where the beading remains fully intact.

Despite a long crack running vertically on the left side and the loss of two leaves from the foliage, the plaque preserves its structural beauty. The back side reveals the ivory’s natural texture, with gentle wavy lines and the subtle trace of a nerve canal, adding to the piece’s authenticity and tactile connection to its organic origins. These characteristics all contribute to the plaque’s historical value, serving as a physical testament to devotion and masterful artistry from the Byzantine era.

The V&A’s ivory plaque of Saint John the Baptist, dating to around 1000 AD, emerges from a period in Byzantine history when art flourished under the Macedonian Dynasty. This era was marked by a “renaissance” of classical themes, blending ancient Greco-Roman styles with Christian iconography and meticulous, refined craftsmanship. The plaque exemplifies this revival through its carefully carved figures and balanced composition, presenting Saint John with an aura of reverence as a ‘bridge’ between the Old and New Testaments. Positioned in the center with a raised hand in benediction, Saint John echoes the imagery of Christ Pantocrator, highlighting his esteemed role as the Forerunner who baptizes Christ. His scroll symbolizes prophetic wisdom, while the saints around him—Philip, Stephen, Andrew, and Thomas—reflect the universal call to discipleship, with inscriptions and red accents further enhancing their significance. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O92548/st-john-the-baptist-and-plaque-unknown/

The original purpose of the plaque remains somewhat uncertain, though the prominence afforded to Saint John the Baptist suggests a possible connection to a religious foundation dedicated to him, such as the renowned Studios Monastery and Basilica in Constantinople. This celebrated institution, a major center of Byzantine monastic life, may have housed objects of similar significance. Following the Crusaders’ sacking of Constantinople in 1204, treasured items from such sites often made their way westward, making it plausible that this plaque was preserved as a valued relic in Europe. Through its symbolism and fine craftsmanship, the plaque reflects both personal devotion and the era’s dedication to spiritual legacy in Byzantine Art.

According to experts at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Byzantine plaque has been stylistically linked to ivory panels on a casket now housed in the Bargello Museum in Florence, which also features half-length depictions of Saints John the Baptist, Philip, Andrew, and Thomas. This connection suggests a shared artistic tradition, reflecting how Byzantine craftsmen used similar motifs and compositions to emphasize the saints’ roles. While my search for a photo and further information on the Bargello casket has been challenging, I hope to view this piece in person during my upcoming visit to the Bargello in the spring! Seeing it firsthand will be invaluable for understanding its stylistic parallels with the V&A plaque. https://www.theflorentine.net/2021/05/04/bargello-museum-reopens-with-refurbished-sala-degli-avori/

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!