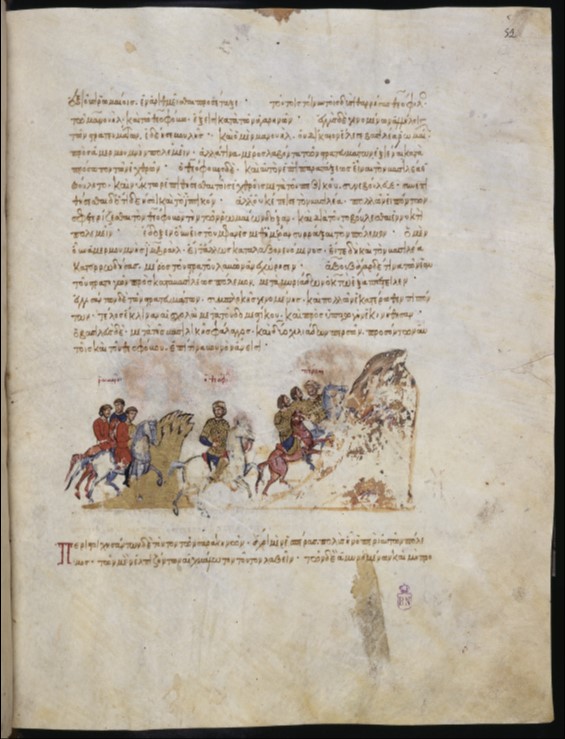

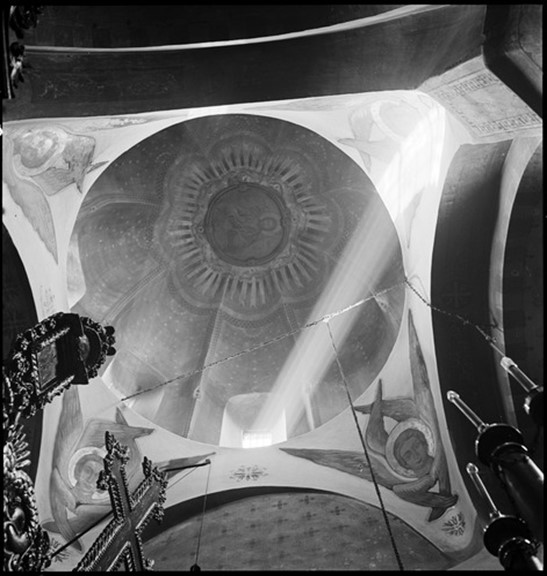

“…denuded of all help, and deprived of human alliance, we were spiritually led on by holding fast to our hopes in the Mother of the Word, our God, urging her to implore her Son, invoking her for the expiation of our sins, her intercession of our salvation, her protection as an impregnable wall for us, begging her to break the boldness of the barbarians, her to crush their insolence, her to defend the despairing people and fight for her own flock…” writes Patriarch Photius in the second of his two homilies on the siege of Constantinople by the Rus’ and Sirarpie der Nersessian, in his 1960 Dumbarton Oaks Papers article titled Two Images of the Virgin, quotes him. I couldn’t find better introductory remarks for a BLOG POST on the marble Icon of The Interceding Theotokos at Dumbarton Oaks. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291145?seq=15#metadata_info_tab_contents page 72 and https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/art/bz/BZ.1938.62.jpg/view

The Dumbarton Oaks Museum is my favourite temple of the Muses in Washington DC! It breathes history, scholarship elegance and class… Its collection of Byzantine Art is top quality, the ways and the hows this collection was acquired fascinates me, the scholarship involved, I believe, is more than appreciated by everyone who loves Byzantium. https://www.academia.edu/3585132/_Royal_Tyler_and_the_Bliss_Collection_of_Byzantine_Art_in_James_N_Carder_ed_A_Home_of_the_Humanities_The_Collecting_and_Patronage_of_Mildred_and_Robert_Woods_Bliss_Washington_D_C_Dumbarton_Oaks_Research_Library_and_Collection_27_50?email_work_card=view-paper “Royal Tyler and the Bliss Collection of Byzantine Art,” in James N. Carder, ed., A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks

https://www.doaks.org/visit/museum/explore/byzantine-gallery

I confess, I first noticed The Marble Interceding Theotokos in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks when I visited the grand Metropolitan Museum Exhibition The Glory of Byzantium back in 1997. Exhibited then, along with the Lips Monastery Icon of Saint Eudokia from the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, the two marble Icons “opened my eyes” in the genre of Sculpted Marble Icons from the Byzantine era. Ever since I seek them out, and when I visit the Museum of Byzantine Culture in my hometown Thessaloniki, I always pay my respects to the marble ΜΗ(ΤΗ)Ρ Θ(ΕΟ)Υ(=Mother of God) Icon in Room 4, where artefacts of the Macedonian and Komnenian dynasties are presented. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Glory_of_Byzantium_Art_and_Culture_of_the_Middle_Byzantine_Era_AD_843_1261 and https://www.mbp.gr/en/object/marble-icon-praying-virgin

The Interceding Theotokos – Virgin Hagiosoritissa Relief, Middle Byzantine, mid-eleventh century, Marble, 104 cm x 40 cm x 7 cm, Dumbarton Oaks Museum, Washington, DC, USA

Praying ΜΗ(ΤΗ)Ρ Θ(ΕΟ)Υ(=Mother of God), 11th century, Marble, 135×70 cm, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece

https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2016/08/saint-eudocia-empress-wife-of-emperor.html

https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/art/bz/BZ.1938.62.jpg/view

https://www.mbp.gr/en/object/marble-icon-praying-virgin

One more confession… the title of this BLOG POST was a decision that troubled me. At Dumbarton Oaks Museum the marble Icon of the Theotokos is presented as Virgin Hagiosoritissa Relief. The Glory of Byzantium Exhibition Catalogue uses a similar name Icon of the Virgin Hagiosoritissa. I thought, this is it…until I started reading Sirarpie der Nersessian article Two Images of the Virgin in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection, and I changed my mind! The author presents in detail the different styles, whereabouts and use of Interceding Theotokos Icons in every medium! Bottom line… I was not convinced the Marble Icon of the Theotokos is of the Hagiosoritissa type… and the title changed to The Interceding Theotokos at Dumbarton Oaks.

For a Student Activity on The Interceding Theotokos at Dumbarton Oaks, please… check HERE!