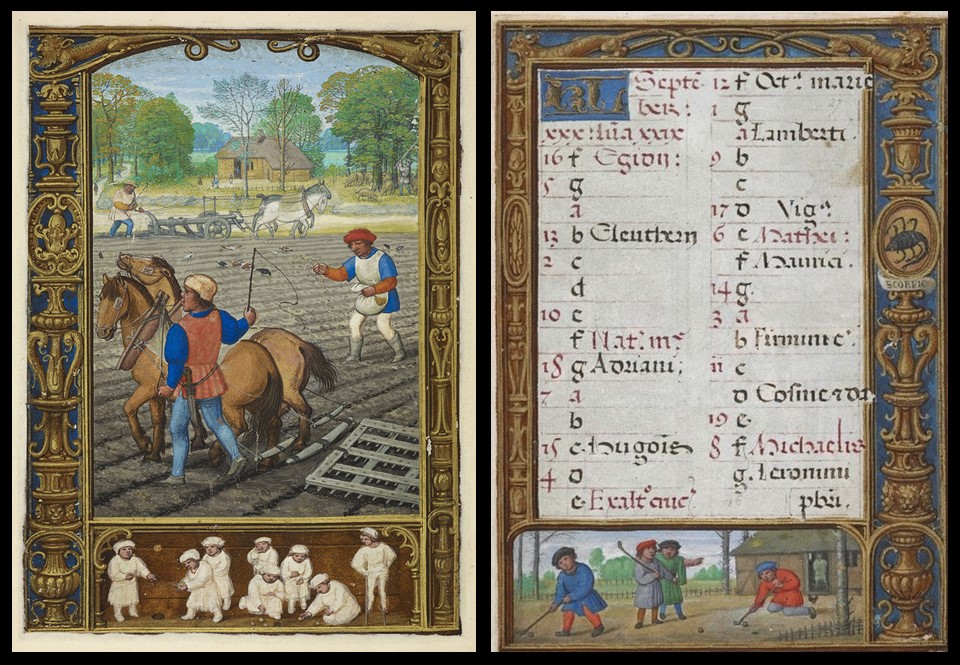

Charon crossing the Styx, 1520 – 1524, Oil on Panel, 64×103 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/charon-crossing-the-styx/c51349b6-049e-476c-a388-5ae6d301e8c1

A horrible ferryman keeps these waters and streams / in fearful squalor, Charon, on whose chin stand enormous, / unkempt grey whiskers, his eyes stand out in flame and / a filthy garment dangles by a knot from his shoulders. / He punts the boat with his pole, handles the sails / and carries bodies across in his murky boat; he is / old now, but for a god old age is raw and green… This is how Virgil describes the Ferryman of the Underworld in his Aeneid… On the other hand, the painting of Charon crossing the Styx by Joachim Patinir presents us with a more serene image of Charon. While he still punts the boat with his pole, he does not exude the same fearsome aura as Virgil’s character. Instead, Patinir’s Charon appears more human and approachable, reflecting the artist’s tendency to soften the harsher elements of myth. https://www.pantheonpoets.com/poems/charon-the-ferryman/

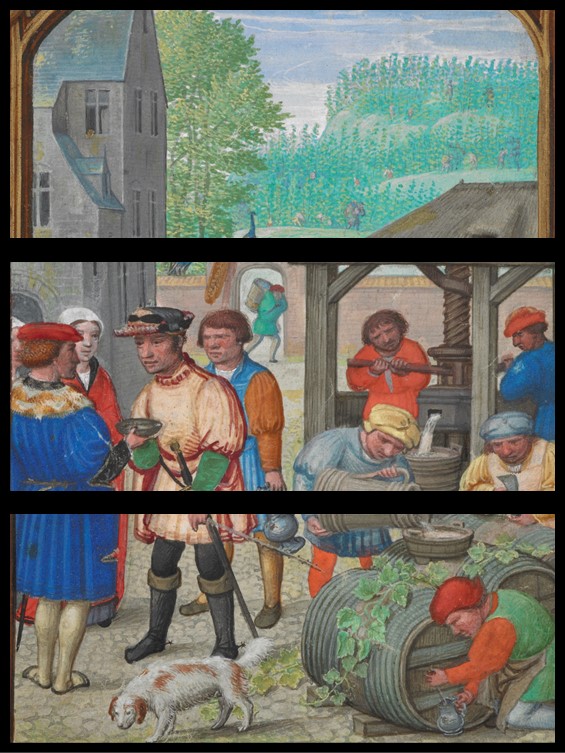

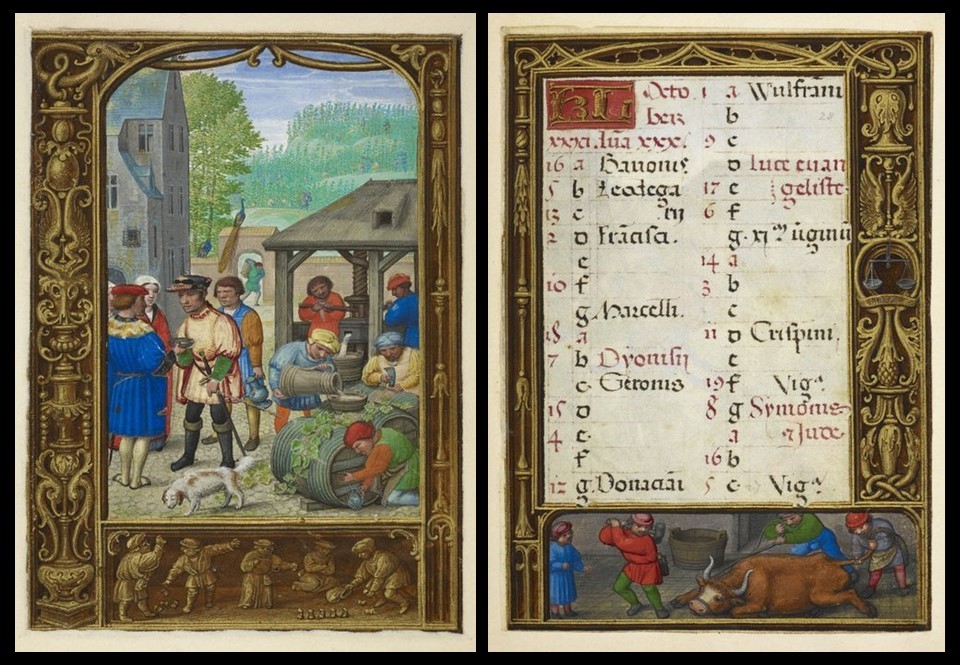

Joachim Patinir’s Charon Crossing the Styx is a masterful example of Northern Renaissance art, encapsulating the technical prowess and the thematic depth characteristic of the period. Painted in the early 16th century, this work illustrates the mythological journey of Charon, the ferryman, transporting souls across the river Styx to the afterlife. Patinir, renowned for his innovative approach to landscape painting, uses the vast, meticulously detailed scenery to heighten the narrative’s dramatic tension. The interplay of light and shadow, combined with symbolic elements embedded within the landscape, invites viewers to explore themes of morality, judgment, and the human condition, making Charon Crossing the Styx a visual feast and a profound philosophical inquiry.

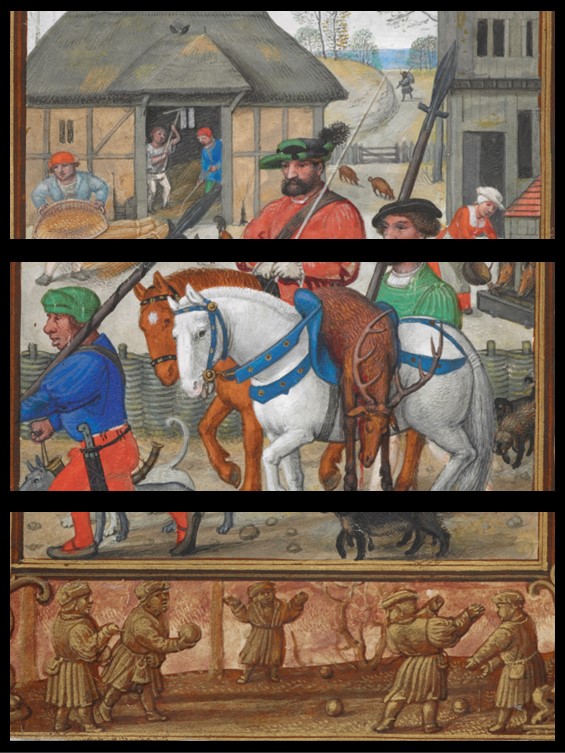

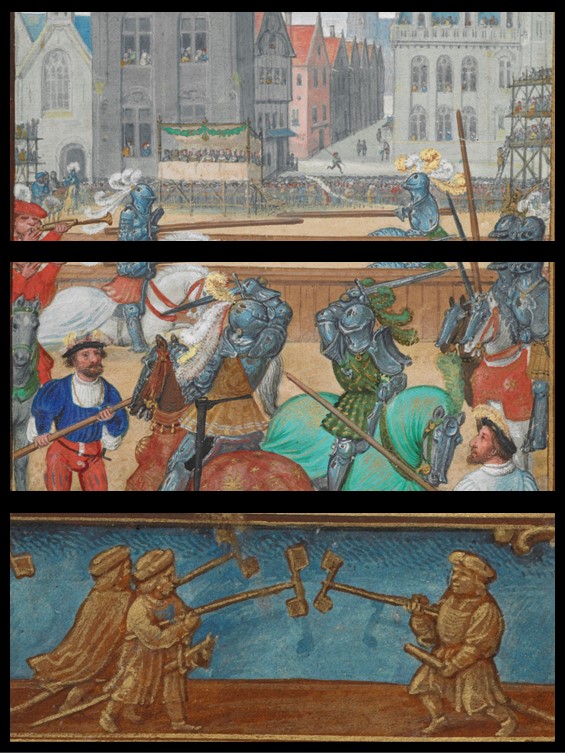

Portrait of Joachim Patinir, between 1585 and 1589, Lead pencil, little pen in grey, over preliminary drawing in pencil, 17.1×13.7 cm, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Germany https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aegidius_Sadeler_(after_Durer)_-_Portrait_of_Joachim_Patinir.jpg

Joachim Patinir, born around 1480 in Dinant or Bouvignes, present-day Belgium, is a significant figure in the Northern Renaissance. Patinir trained and worked in Antwerp, which was a major cultural hub during his lifetime. Though not much is known about his personal life, records indicate that he joined the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke in 1515, solidifying his status as a master painter. His career was relatively brief as he died in 1524, yet he left a lasting impact on the art world, particularly through his contributions to landscape painting. Patinir’s works often blend religious themes with expansive, detailed landscapes, earning him recognition and admiration among his contemporaries and subsequent generations.

Patinir’s artistic style is characterized by his pioneering approach to landscape painting, which he often used as a primary subject rather than merely a backdrop. His compositions are notable for their meticulous detail, vibrant use of colour, and imaginative integration of natural and fantastical elements. Patinir’s landscapes are typically vast and panoramic, with a high horizon line that allows for an expansive view of the natural world. This technique creates a sense of depth and scale, inviting viewers to immerse themselves in the scenery. Additionally, his works frequently incorporate symbolic elements that enhance the narrative and thematic depth, such as rivers representing the journey of life and mountains symbolizing spiritual ascent. Patinir’s ability to fuse human figures within these grand landscapes seamlessly showcases his unique vision and has earned him a lasting legacy in art history.

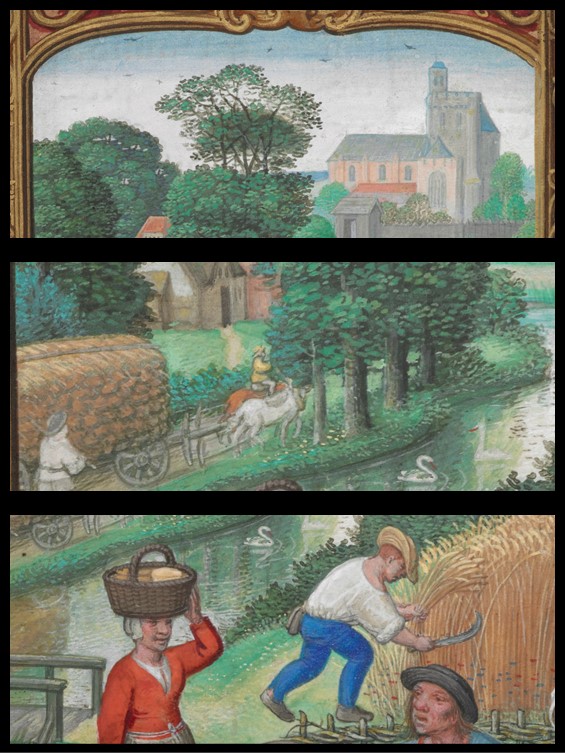

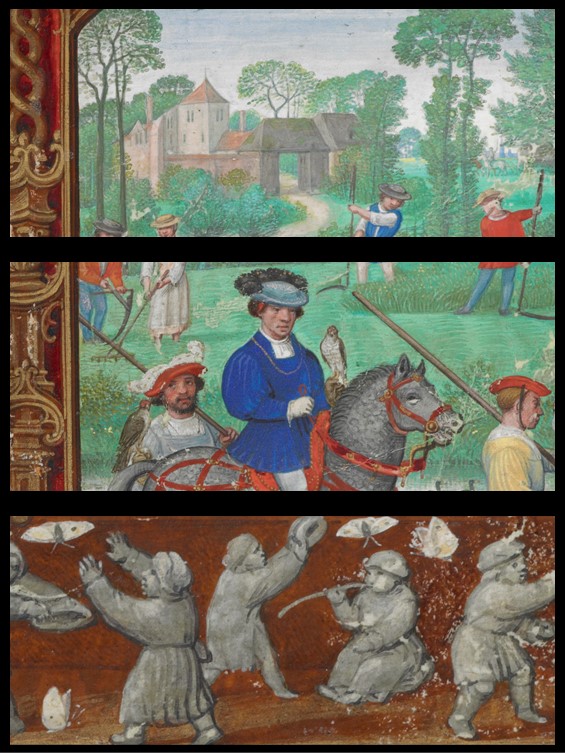

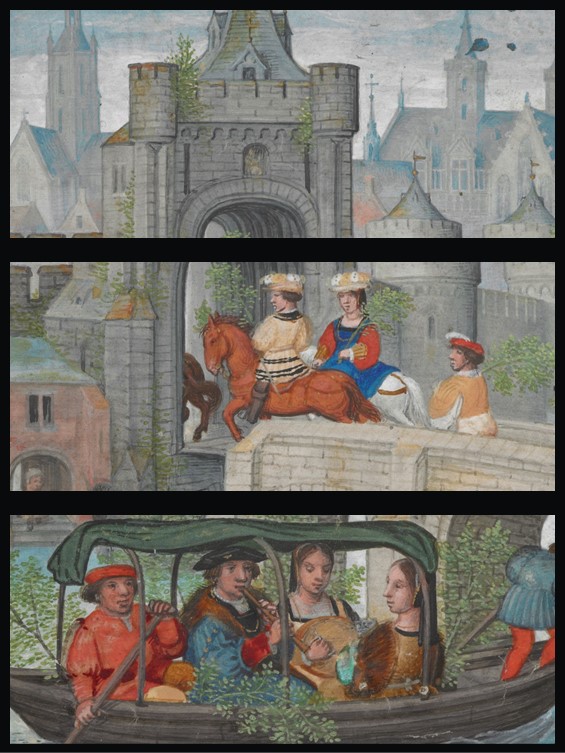

Charon crossing the Styx (detail), 1520 – 1524, Oil on Panel, 64×103 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://canon.codart.nl/artwork/landscape-with-charon-crossing-the-styx/

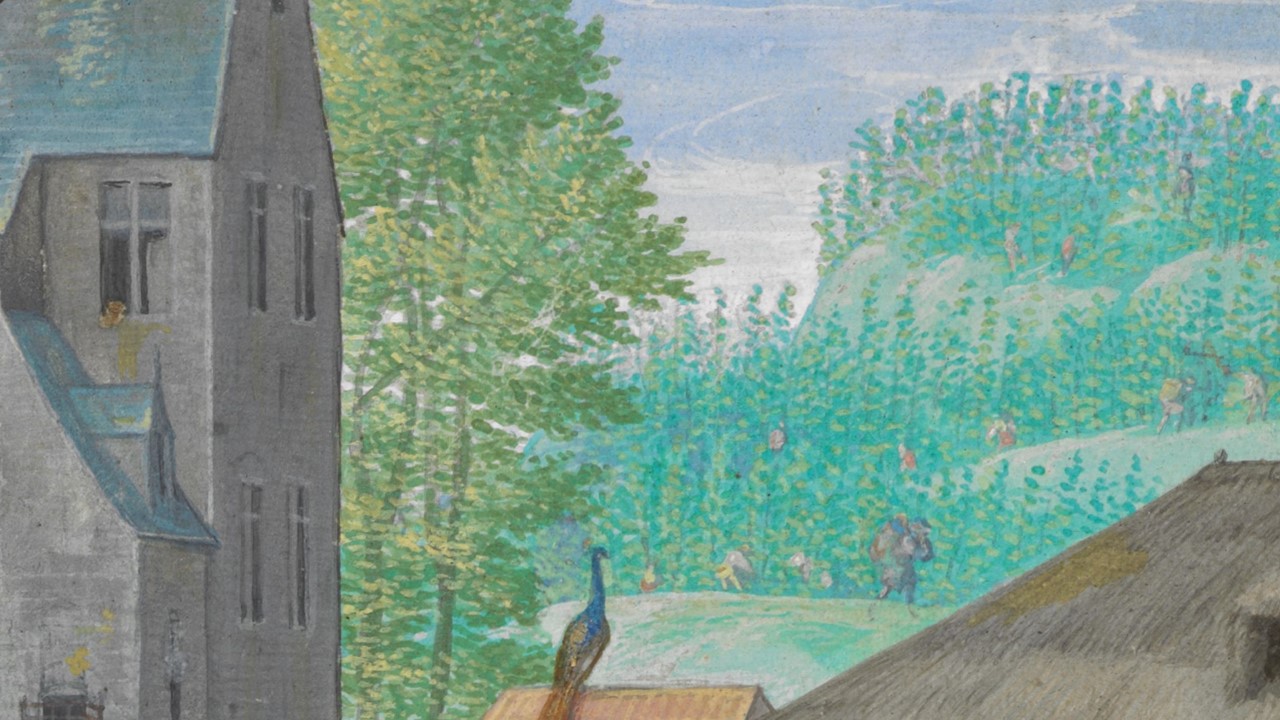

Charon Crossing the Styx by Joachim Patinir, housed in the Prado Museum, is a striking example of Flemish Renaissance landscape painting. Created around 1520-1524, this work captures the mythological scene of Charon ferrying souls across the River Styx to the underworld. Patinir’s detailed landscape divides the canvas space vertically into three zones: one on either side and the third occupied by the broad river in the center, on whose opaque and mirror-like surface Charon steers his boat. Patinir’s detailed landscape juxtaposes a lush, heavenly paradise on the left and a barren, hellish domain on the right. For the iconography of this subject, Patinir draws together biblical images and classical sources. An angel on the promontory, another two accompanying the souls not far away, and a few more with other tiny souls in the background allow us to recognize the paradise on the left as a Christian heaven, not the Elysian Fields. On the other hand, the dog Cerberus seems to identify the inferno shown on the right as Hades, thus associating it with Greek mythology, as do Charon and his boat. Charon’s boat, carrying a solitary soul, navigates the murky waters between these symbolic worlds. The painting is notable for its meticulous detail, vivid colouration, and dramatic interplay between light and shadow, encapsulating the moral dichotomies of salvation and damnation.

Charon crossing the Styx (detail), 1520 – 1524, Oil on Panel, 64×103 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://canon.codart.nl/artwork/landscape-with-charon-crossing-the-styx/

Charon crossing the Styx (detail), 1520 – 1524, Oil on Panel, 64×103 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://canon.codart.nl/artwork/landscape-with-charon-crossing-the-styx/

According to Prado Museum experts, Patinir’s painting is inspired by St Matthew`s Gospel, and …reflects the pessimism of his turbulent times, with the Protestant Reformation gaining momentum after the appearance of Martin Luther`s Ninety-Five Theses in Wittenberg in 1517… and thus converts this work into a memento mori, a reminder to all those who contemplate it that they must prepare for the moment of death, and that the hard road must be chosen in imitation of Christ, ignoring false paradises and deceitful temptations.

It is not known what prompted Patinir’s patron to commission this work or where it was meant to hang. Evidently, it is not an altarpiece but a cabinet painting, suited to a humanist environment. The painter, likely with help from a client or mentor, drew inspiration from earlier depictions of heaven and hell, emphasizing the role of landscape and reducing the number of demons and damned souls on the Underworld’s side. Both the drawing and the colour handling indicate this painting was an autograph work by Patinir, as the central figure of Charon shows his distinctive style.

Charon Crossing the Styx remains a significant work in art history, showcasing Patinir’s artistic skill and his ability to convey complex themes through visual art. Seen as a masterpiece that exemplifies the depth and innovation of Northern Renaissance art, and combines mythological narrative with an unprecedented focus on landscape to explore profound human themes, Patinir’s Charon Crossing the Styx is a vision to hold!

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Joachim Patinir’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!