Daisies, 1939, Oil on Canvas, 92 × 65 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, USA https://www.artic.edu/artworks/100226/daisies

The painting Daisies by Henri Matisse, housed in The Art Institute of Chicago, captures the quiet radiance of nature with his signature bold colours and fluid brushwork. The daisy, the flower of April, symbolizes purity, resilience, and new beginnings—qualities that resonate deeply in Matisse’s luminous arrangement of white blossoms against a vibrant backdrop. His depiction calls to mind Emily Dickinson’s tender lines: “The daisy follows soft the sun, / And when his golden walk is done, / Sits shyly at his feet. / He, waking, finds the flower near. / ‘Wherefore, marauder, art thou here?’ / ‘Because, sir, love is sweet!’” Like Dickinson’s poetic daisy, Matisse’s flowers seem to bask in an unseen glow, embodying an intimate conversation between light and form, simplicity and devotion. https://discoverpoetry.com/poems/daisy-poems/

Matisse’s Daisies, is a joyful still-life that captures his fascination with colour, light, and organic forms. The painting presents a bouquet of white daisies arranged in a transparent glass vase, set against a stark black background and ‘accompanied’ by the artist’s model, seated on a bright red chair, outlined with thick, fluid, black lines, as well as a pink-and-blue drawing of another woman on the upper left side of the painting. The vase of Daisies is part of a Still Life arrangement organized on the right side of the painting. It consists of a green amphora, a vase of flowers, and lemons atop a tall light-blue table. Matisse employs bold brushstrokes, layering warm yellows, deep reds, and rich greens that contrast with the crisp white petals of the daisies. Though simply rendered, the flowers exude an unmistakable vibrancy, as if swaying gently in an unseen breeze. The composition balances structure and fluidity—while the vase anchors the scene, the blossoms extend outward, softly blending into the surrounding space.

Aesthetically, Daisies exemplifies what Matisse called “ballast,” a technique of adding and removing paint to achieve the desired effect of light. Rather than aiming for photographic realism, he distills the essence of the subject through bold contours and a dynamic interplay of warm and cool hues. The daisy—a flower often associated with innocence and renewal—becomes a vehicle for Matisse’s exploration of harmony, light, and movement. The painting’s flattened perspective and luminous palette reflect his belief in art’s ability to evoke joy and emotional depth rather than mere representation. The background, composed of dappled brushstrokes in yellow and red, creates a sense of warmth and intimacy, drawing the viewer into a world where nature and art converge in pure, expressive beauty.

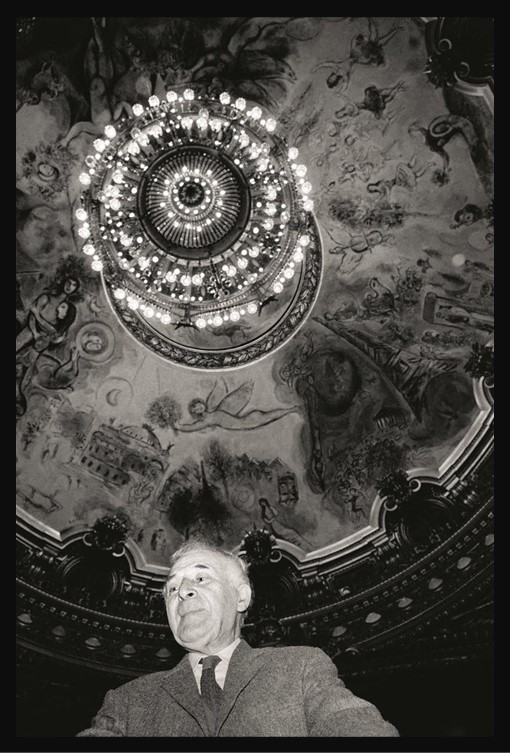

At the Jeu de Paume Museum, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, painting in his left hand and cigar in his right, sits gazing at two works by Henri Matisse being supported by Bruno Lohse. Standing to Göring’s left is his art advisor, Walter Andreas Hofer. Note the bottle of champagne on the table. Both paintings were stolen from the Paul Rosenberg collection by the Nazis and were recovered and returned after the war. The painting on the left, ‘Marguerites’, today hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. The other, ‘Danseuse au Tambourin’, is at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California. mage credit: Archives des Musées Nationaux https://artuk.org/discover/stories/art-matters-podcast-the-monuments-men-and-preserving-art-during-war

Created during a pivotal period in Matisse’s career, Daisies was painted in 1939, just as the world teetered on the brink of World War II. Despite the looming global turmoil, Matisse continued to explore the themes of serenity and vitality that defined much of his work. Daisies was initially acquired by the renowned modern art dealer Paul Rosenberg (1881–1959). However, with the Nazi occupation of France, Rosenberg, like many other Jewish dealers, was forced to flee, and his extensive collection, including Daisies, was seized. After World War II, the painting was among the works recovered by the U.S. Army’s efforts to restitute looted art. Rosenberg reclaimed Daisies and brought it to his newly established gallery in New York. Eventually the painting became part of The Art Institute of Chicago’s collection, where it remains a cherished example of Matisse’s lifelong pursuit of beauty through simplified, evocative forms.

Henri Matisse (1869–1954) was a pioneering French artist whose bold use of color and fluid forms reshaped modern art. Initially trained in law, he discovered painting in his early twenties and soon became a leading figure in Fauvism, a movement defined by vibrant, expressive color. Throughout his career, Matisse continuously experimented with composition, perspective, and light, moving from the vivid hues of his Fauvist period to the refined, decorative harmony of his later works. Even as he faced illness in his later years, he adapted his creative process, embracing cut-outs and paper collages as a new medium for artistic expression. His 1939 painting Daisies reflects this lifelong pursuit of joy and balance, distilling nature into a symphony of colour and form. Like much of his work, it transcends simple representation, instead capturing the emotional essence of its subject—transforming an ordinary bouquet into an emblem of vitality and renewal.

Daisies are often associated with April because they symbolize purity, new beginnings, and resilience—qualities that align with the themes of springtime renewal. As one of the first flowers to bloom widely across fields and gardens when winter recedes, daisies represent the fresh start that April brings. Their name comes from the Old English “dæges ēage” (day’s eye), referring to their habit of opening with the sun and closing at night, further reinforcing their connection to the longer, sunlit days of early spring. In floral traditions, the daisy is often linked to innocence, love, and transformation, making it a fitting emblem for a month that bridges the transition from the softer, budding days of March to the full bloom of late spring.

For a Student Activity, inspired by Matisse’s Daisies, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://publications.artic.edu/matisse/reader/works/section/87 and https://www.artic.edu/artworks/100226/daisies