https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2017/chaniotis-world-of-emotions

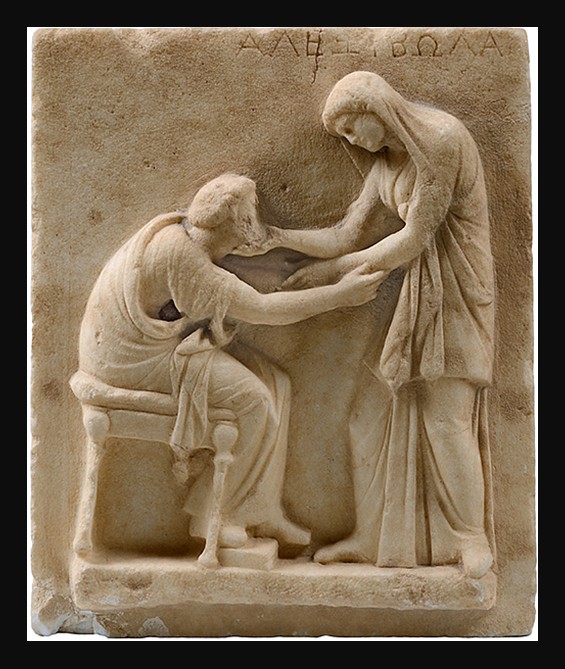

Among the treasures of the Archaeological Museum of Thera, the Funerary Stele of Alexibola stands out as a moving testament to the emotional depth of Classical Greek art. Carved in marble in the early 3rd century BC, the relief depicts Alexibola, the deceased, standing before a seated older man, probably her father, as they exchange a final, tender farewell. The woman’s gesture, gently touching the man’s beard, is met by his reciprocal touch on her arm, creating a moment of quiet intimacy and profound affection. Their calm expressions and composed postures convey sorrow and love without excess, embodying the Greek ideal of dignity even in grief.

Displayed in the acclaimed 2017 exhibition “A World of Emotions: Greece, 700 BC–AD 200” (Onassis Cultural Center, New York; Acropolis Museum, Athens), this stele beautifully illustrates how emotion was central to Greek experience. As curator Angelos Chaniotis observed, emotions shaped Greek culture no less than reason. The stele of Alexibola reveals how artists of the Classical world captured not only the likeness of individuals but also the enduring human capacity for feeling, transforming private loss into timeless art.

Funerary stelae held a vital place in ancient Greek art, serving as both commemorations of the dead and reflections of deeply personal emotion within a public setting. These marble reliefs, often depicting the deceased in moments of quiet interaction with loved ones, reveal how the Greeks balanced restraint and feeling, translating private grief into graceful, idealized form. Rather than dramatic displays of sorrow, they communicate emotion through subtle gestures: a clasped hand, a downward gaze, or a tender touch. The Stele of Alexibola exemplifies this tradition perfectly, its depiction of a final farewell between a daughter and her father transforms the pain of parting into a timeless image of love, respect, and composure. Through such works, Greek artists gave emotional depth to stone, reminding viewers that even in death, the bonds of human affection endure.

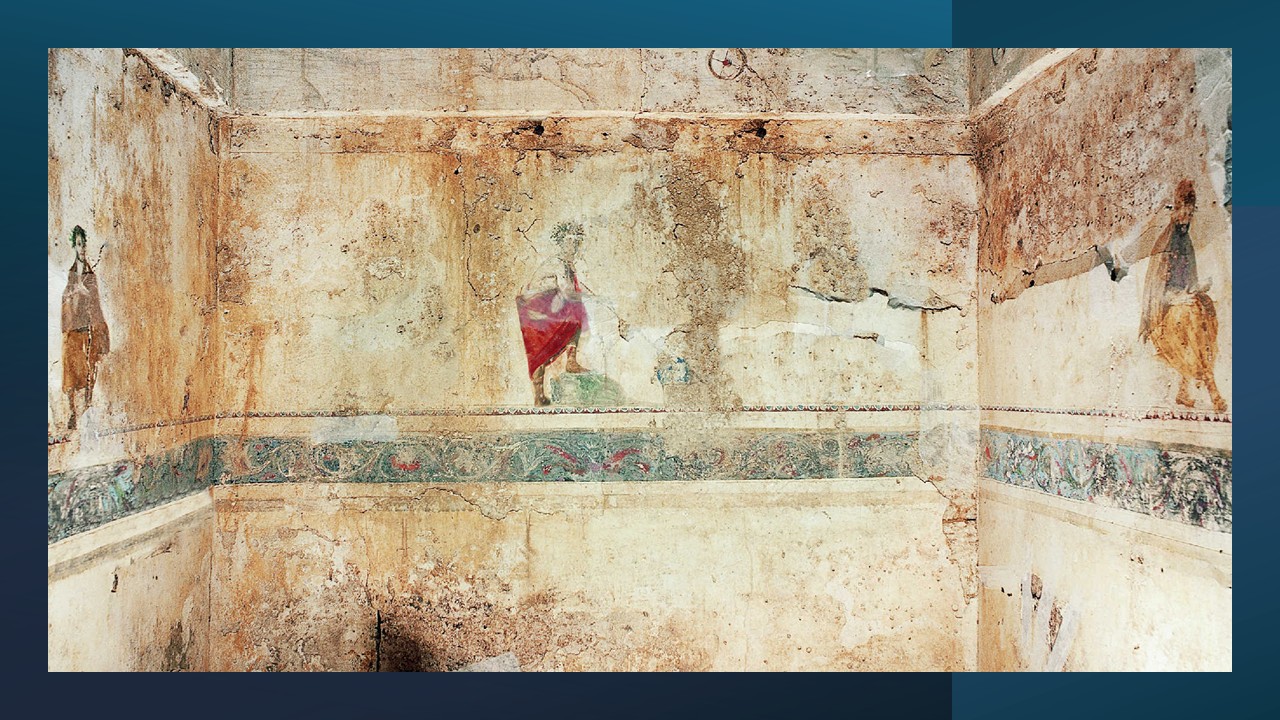

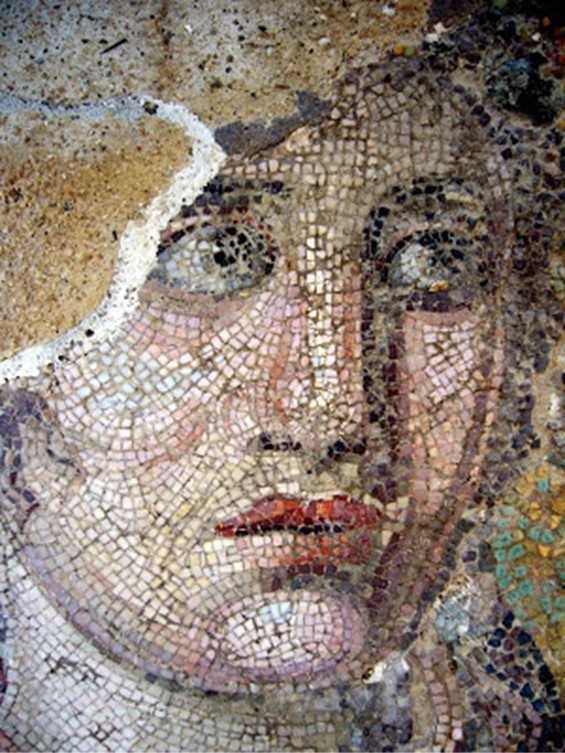

The Funerary Stele of Alexibola was discovered on the Cycladic island of Thera, modern Santorini, an island that has long held a significant place in the history of Greek art and culture. Thera was a thriving center of Aegean civilization, strategically located between Crete and mainland Greece, and its artistic legacy reflects this blend of influences. From the vivid frescoes of the prehistoric settlement at Akrotiri, which reveal a sophisticated visual culture rivaling that of Minoan Crete, to later Classical and Hellenistic sculptures such as the stele of Alexibola, Thera demonstrates the island’s continuous engagement with the broader artistic currents of the Greek world. The stele itself embodies the island’s role as both participant in and preserver of Greek aesthetic value, melding technical mastery with emotional subtlety, and reminding us that even on this volcanic outpost, art served as a bridge between personal memory and collective tradition.

https://www.greece-is.com/millennia-tour-santorini-ages/

Today, the Funerary Stele of Alexibola continues to speak across millennia, its message as clear and touching as when it was first carved. In its quiet grace, we recognize the timeless human emotions of love, loss, and remembrance, feelings that unite us with those who lived and grieved long ago. The simplicity of the figures, their tender gestures, and the dignified calm of their farewell remind us that art can express what words often cannot. Through Alexibola’s parting moment with her father, we are invited into an intimate world where ancient stone becomes a vessel for enduring emotion, proving that even in silence, the human heart has always sought connection, beauty, and meaning.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of important ancient Greek Funerary Stele, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2017/chaniotis-world-of-emotions

More Posts on ancient Greek Funerary Stele by Teacher Curator… https://www.teachercurator.com/art/hegeso-daughter-of-proxenos/ and https://www.teachercurator.com/ancient-greek-art/telling-us-goodbye/ and https://www.teachercurator.com/ancient-greek-art/grave-stele-of-a-youth-and-a-little-girl/