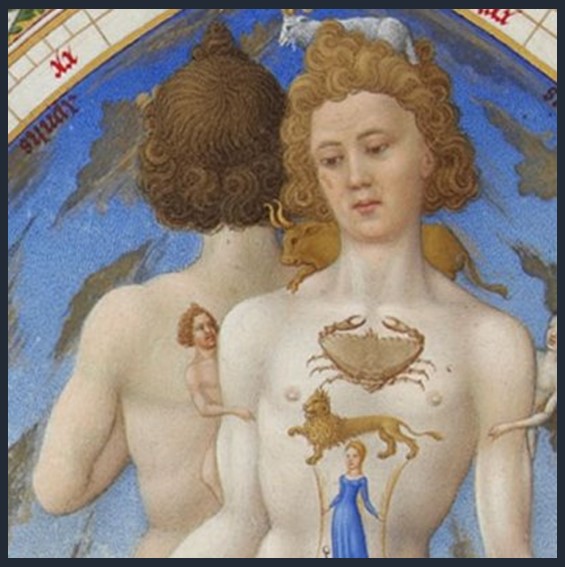

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Anatomical Man/Zodiac Man (folio 14v), 1413-16, Painting on Vellum, 30×21 cm, Museum Conde, Chantilly, France https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anatomical_Man.jpg

The Limbourg Brothers were a trio of Dutch Renaissance painters: Herman, Paul, and Johan Limbourg from Nijmegen. They are most famous for their work on the illuminated manuscript Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry), which they created in the early 15th century. This manuscript is considered one of the masterpieces of French International Gothic Art. The brothers were known for their meticulous attention to detail and their ability to capture the richness of color and texture in their work. Unfortunately, their careers were cut short when they died at a young age, possibly due to the bubonic plague. Despite their short lives, their contributions to art and illumination continue to be celebrated and studied today.

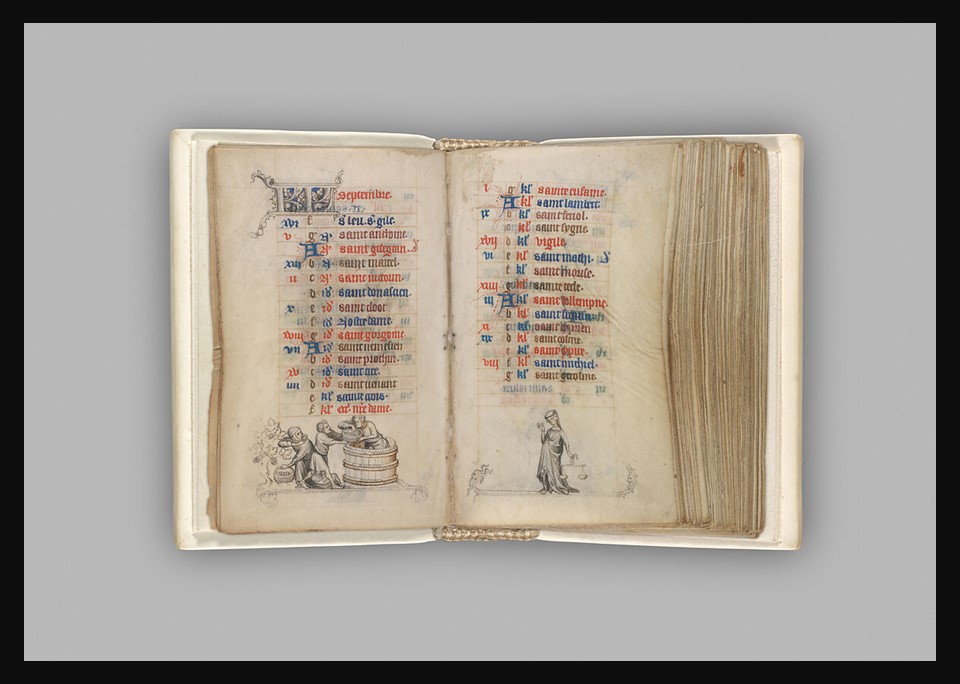

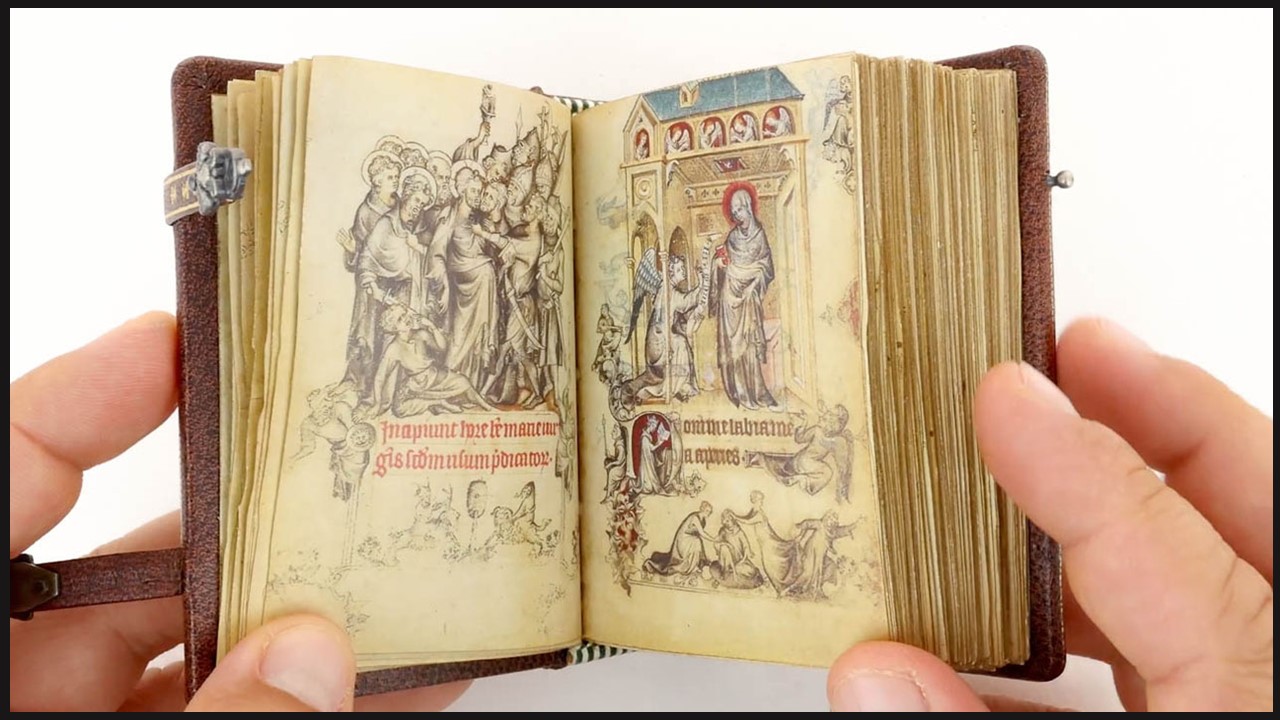

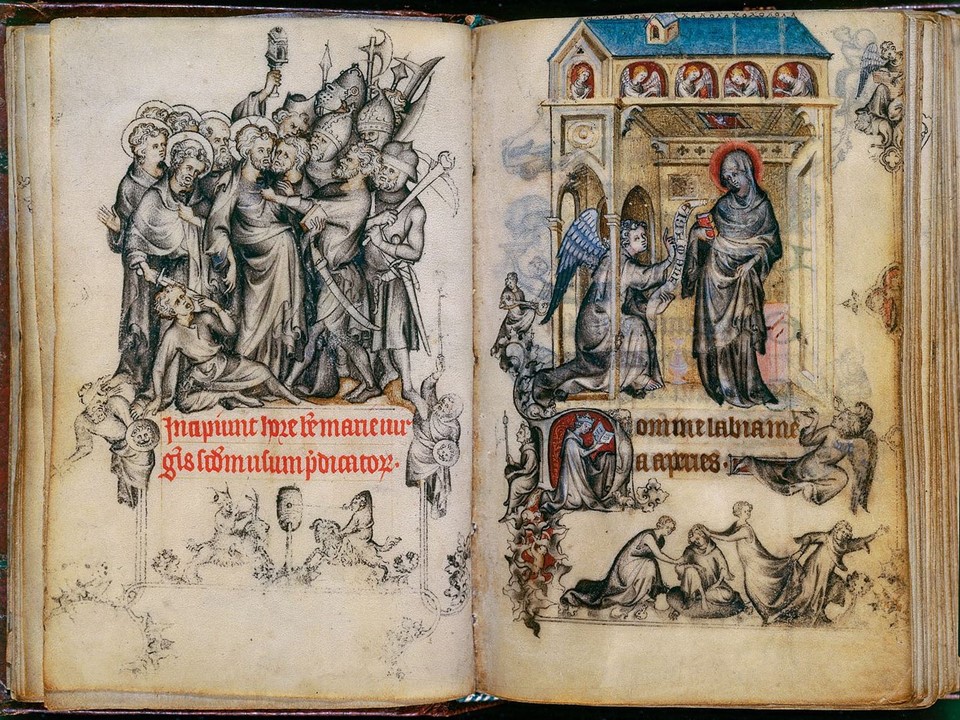

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is an exquisite, illuminated manuscript that stands as a masterpiece of artistry and cultural heritage. Commissioned by Jean de Valois (1340-1416), Duc de Berry, in the early 15th century, between c. 1412 and 1416, this lavishly decorated Book of Hours captures the essence of the era’s religious devotion, aristocratic splendor, and the beauty of the natural world. Created by the Limbourg brothers, but never completed, it showcases their unparalleled skill in miniature painting, with each page a vibrant tapestry of intricate details and vivid colors. Beyond its artistic magnificence, the manuscript serves as a window into the opulent lifestyle and spiritual fervor of the medieval French court, making it a treasured relic of both artistic and historical significance.

An anonymous painter, widely speculated by art historians to be Barthélemy d’Eyck, undertook further embellishments for the unfinished manuscript in the 1440s. Subsequently, between 1485 and 1489, the manuscript underwent significant modifications by the painter Jean Colombe, acting on behalf of the Duke of Savoy, ultimately achieving its present state. Following its acquisition by the Duc d’Aumale in 1856, the book now resides as MS 65 in the Musée Condé, located in Chantilly, France.

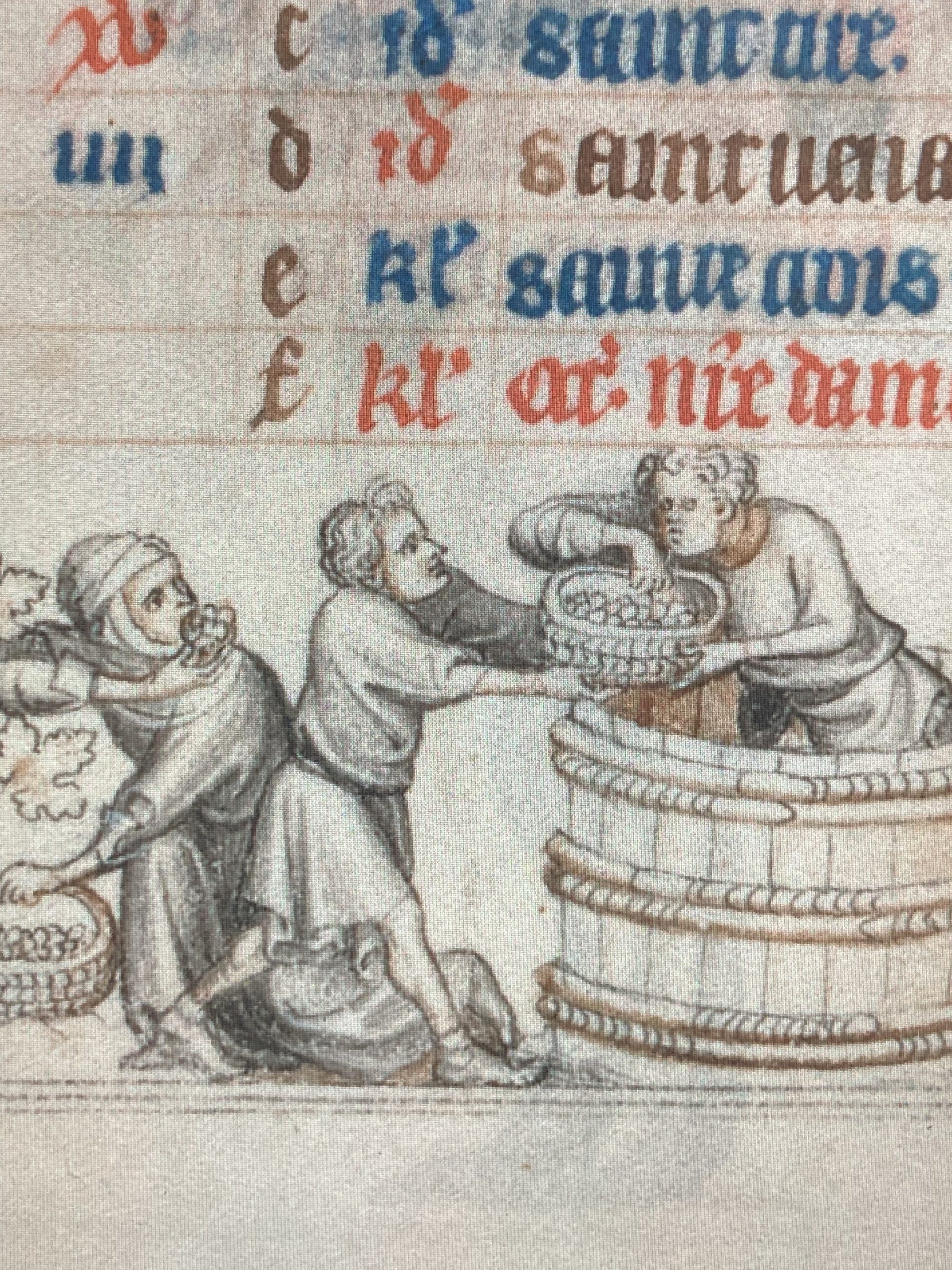

This amazing manuscript is a collection of prayers to be said at the canonical hours. It contains a rich assortment of religious texts, prayers, and beautifully illustrated scenes depicting the liturgical calendar and the life of Christ. Its pages feature elaborate depictions of saints, biblical events, the months of the year, and scenes from everyday life, meticulously crafted with intricate details and vibrant colors. Additionally, the manuscript includes annotations, psalms, and devotional readings tailored for personal prayer and reflection. Beyond its religious content, the manuscript also offers glimpses into the aristocratic life, and the life of the peasants, of the time, with illustrations of courtly gatherings, hunting scenes, idyllic landscapes, and peasant chords. Each page is a testament to the skill of the Limbourg brothers and their mastery of the art of illumination, making it a captivating blend of religious devotion, artistic excellence, and historical insight.

Folio 14v, the manuscript’s page presenting the Anatomical or Zodiac Man, is a rare motif in medieval art, an elusive miniature, a unique iconography, and a riddle for all scholars involved in interpreting its meaning. Folio 14v is my personal favourite!

Against a backdrop of magnificent blue skies adorned with golden clouds, two naked men stand back-to-back at the center of the mandola-shaped composition. Within the body frame of the human figure facing the viewer, the manuscript artists present the twelve Signs of the Zodiac. Each Sign, meticulously arranged and governing a specific part of the body, is steeped in the medieval belief— a Hellenistic inheritance, to be precise— in astrological medicine. This belief posited that the movements of celestial bodies influenced health and bodily functions. The second figure, as presented by the Limbourgs, is the most enigmatic aspect of the composition. Seen from the back in a mirror-like reflection, this figure starkly contrasts with the first. Not adorned with Zodiacal Signs, he possesses auburn hair, and his arms are positioned differently. Together, they remain open to interpretation, lacking a definitive explanation.

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Anatomical Man/Zodiac Man (detail), 1413-16, Painting on Vellum, 30×21 cm, Museum Conde, Chantilly, France

https://utpictura18.univ-amu.fr/notice/19788-homme-anatomique-tres-riches-heures-duc-berry-limbourg

The Anatomical or Zodiac Man is framed by three mandola-shaped bands. The outermost band corresponds to the 360 degrees of the circle of heavens, scaled and sub-divided into twelve thirty-degree sectors, each corresponding to one zodiacal constellation. The inner band marks the days of each month for the entire year. The calibrations are precisely synchronized so that each month spans the interval from the exact mid-point of one sign to that of its successor. https://www.jstor.org/stable/750460?read-now=1&seq=4#page_scan_tab_contents Harry Bober The Zodiacal Miniature of the Très Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry: Its Sources and Meaning Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 11 (1948), pp. 1-34 (45 pages)

Within the outer bands, which are narrow in size, the Limbourg brothers positioned a wider band, beautifully adorned in green, blue, and gold, where a second set of the twelve Zodiac Signs is shown. Meticulously rendered, each Sign highlights the Limbourg brothers’ mastery of detail and design. The mandola shape of the band is further accentuated by the incorporation of the Zodiac Signs within similarly mandola-shaped designs. Together, they enrich the folio’s aesthetic appeal, contributing to a harmonious visual balance that complements the central figure’s anatomical depiction. Through this carefully crafted frame, the manuscript not only presents scientific knowledge but also elevates it to an aesthetic realm, inviting viewers to explore the interconnectedness of earthly and celestial phenomena.

In a captivating display of detail, the illumination’s apexes are adorned with the heraldic symbols representing the Duke of Berry, lending an air of regal splendor to the manuscript’s margins. Positioned alongside these symbols are four Latin inscriptions, each describing the characteristics attributed to the Zodiac Signs based on their complexions, temperaments, and cardinal points. In the upper left, Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius are depicted as fervently warm and dry, imbued with the fiery essence of the choleric temperament, and bearing the masculine energy of the East. Meanwhile, the upper right unveils Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn, enveloped in a cold and dry temperament, steeped in melancholy, and embracing the feminine allure of the Western realm. Descending to the lower left quadrant, Gemini, Aquarius, and Libra emerge with a vibrant warmth and humidity, embodying the sanguine spirit, and exuding the masculine vigor of the Southern domain. Finally, the lower right quadrant unveils Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces, cloaked in a chilly dampness, embodying the phlegmatic essence, and emanating the tranquil femininity of the Northern expanse. This interplay of symbolism and description not only enriches the visual tapestry but also invites contemplation on the interconnectedness of celestial forces and human attributes.

The depiction of the Anatomical or Zodiac Man in the Limbourg brothers’ manuscript Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry exudes a captivating aesthetic that seamlessly intertwines scientific inquiry with artistic mastery. Positioned within the intricate framework of medieval illumination, the figure emerges as a harmonious blend of anatomical precision and symbolic richness. Each rendered detail, from the delicate lines delineating the body’s proportions to the illustrated Zodiac Signs, invites contemplation and admiration. The vibrant hues of the illuminations, delicately applied gold leaf, and intricate patterns that adorn the margins further enhance the visual allure, drawing the viewer into a mesmerizing exploration of the human form and its cosmic connections. This fusion of artistic technique and intellectual curiosity epitomizes the manuscript’s exquisite aesthetic, offering a window into both the scientific knowledge and artistic sensibilities of the era.

For a PowerPoint Presentation on the Limbourg Brothers, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://les-tres-riches-heures.chateaudechantilly.fr/ and https://www.jstor.org/stable/750460?read-now=1&seq=4#page_scan_tab_contents