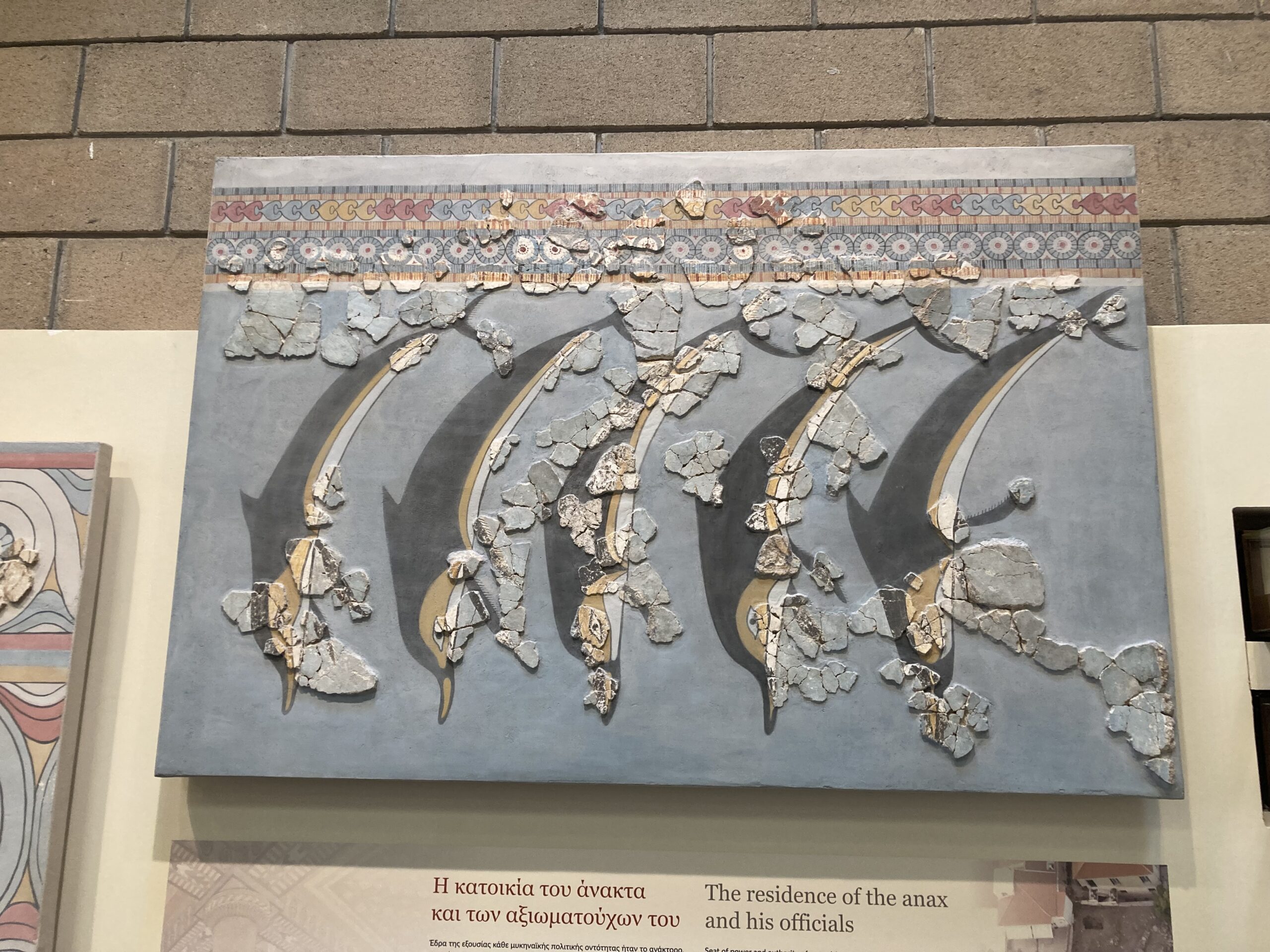

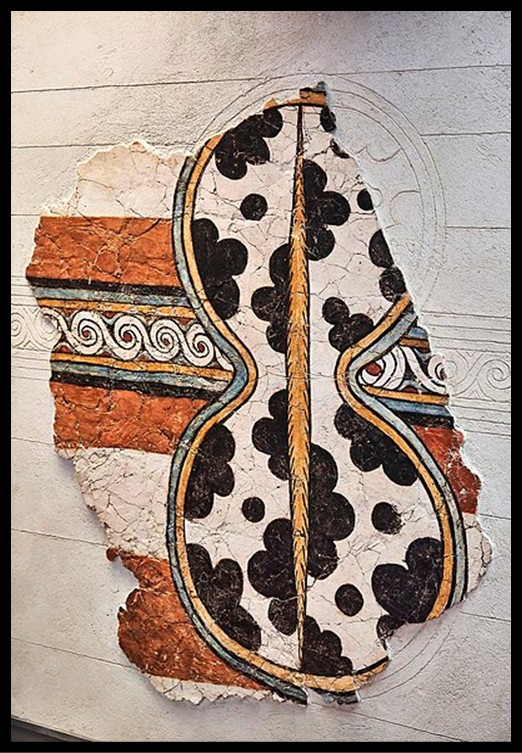

Fresco from the Cult Center of the Acropolis

of Mycenae, 1250-1180 BC, National Archaeological Museum

of Athens, Greece https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mycenaean_mural_

depicting_a_shield_at_the_National_Archaeological_Museum_of_Athens_on_October_26,_2021.jpg

The Figure of Eight Shield is a distinctive type of shield originating in the Aegean region, particularly prominent during the Late Bronze Age. Its unique design, resembling the number ‘8’, featured a curving outline that provided comprehensive protection while allowing for ease of movement. Typically constructed from a wooden frame, it was reinforced with layers of leather or metal to enhance durability and resistance in combat. This shield is closely associated with the warrior culture of Mycenaean Greece and is frequently depicted in frescoes and artifacts from that period, symbolizing both practicality and status in the martial practices of the time.

Let me present you with ’10 Facts’ about the amazing Figure of Eight Mycenaean Shields!

Unique Shape: The ‘Figure of Eight’ shield was shaped like two large, connected ovals, creating a narrow waist-like middle. This design not only made it visually distinctive but also allowed for a balance between size and ease of handling.

Large Size: These shields were massive, often covering a soldier from head to toe, providing extensive body protection. Their size was advantageous in phalanx formations or defensive stances but made them cumbersome in fast, mobile combat.

Construction Materials: The construction of the ‘Figure of Eight’ shields reflects the technological ingenuity of the Mycenaeans. The core of the shield was typically a wooden frame, chosen for its balance of strength and lightness, allowing the shield to remain functional despite its large size. The wooden frame was then covered with multiple layers of tightly stretched cowhide, often up to several layers thick, which added durability and the ability to absorb impact from weapons like spears and arrows. To further enhance their strength, some shields were reinforced with bronze fittings or edging. These metal elements made the shields more resistant to slashing or piercing blows, ensuring they could withstand the demands of battle. Additionally, the cowhide was sometimes treated with oils or other substances to make it more durable and less susceptible to wear from environmental factors like moisture. These materials worked in harmony to produce a shield that was both protective and flexible, suited for the needs of Mycenaean warriors in close combat or defensive formations.

Mycenaean Dagger Blade with Hunters attacking Lions, c. 1,600-1,500 BC, inlaid in gold, silver and niello, National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece https://archeology.dalatcamping.net/the-bronze-legacy-unveiling-the-artistry-of-mycenaean-daggers/

Artistic Depictions: Artistic depictions of the ‘Figure of Eight’ shields are found in various media, including frescoes, pottery, and engraved seals, offering valuable insights into their role in Mycenaean and Minoan societies. Frescoes from palatial sites like Knossos and Tiryns often show warriors wielding these shields, emphasizing their importance in both warfare and ceremonial contexts. Seal engravings, frequently detailed and symbolic, also depict the shields, suggesting their association with elite status or divine protection. Such representations indicate that the shields were not just practical tools for defense but also symbols of power, prestige, and cultural identity in the Late Bronze Age.

Use in Warfare: The shield was designed for full-body protection, particularly in close combat or during sieges. Its large size made it especially effective against projectile weapons, though it required significant strength to wield.

Ceremonial and Symbolic Roles: These shields were likely used in rituals or as symbols of power, as seen in artistic representations. Their association with elite warriors or deities underscores their importance beyond mere battlefield use.

Origins and Chronology: The ‘Figure of Eight’ shield originated in the Late Bronze Age, around 1600 BCE, and was likely influenced by earlier Minoan designs. It fell out of use by the end of the Bronze Age as combat tactics evolved.

Flexibility and Mobility: The narrow middle of the shield allowed soldiers to maneuver it more easily despite its large size. This feature improved mobility in combat, making it versatile for both offense and defense.

Decline in Use: By the 12th century BCE, the ‘Figure of Eight’ shield was replaced by smaller, lighter designs like circular or tower shields. This change reflected the increasing importance of agility and individual mobility in warfare.

Connection to Homeric Epics: Homer’s descriptions of large shields, though generally round, may have been inspired by earlier designs like the ‘Figure of Eight.’ These shields serve as a link between Mycenaean warfare and later Greek military traditions.

For a PowerPoint on Student Activities inspired by the Mycenaean Shields, please… Check HERE!