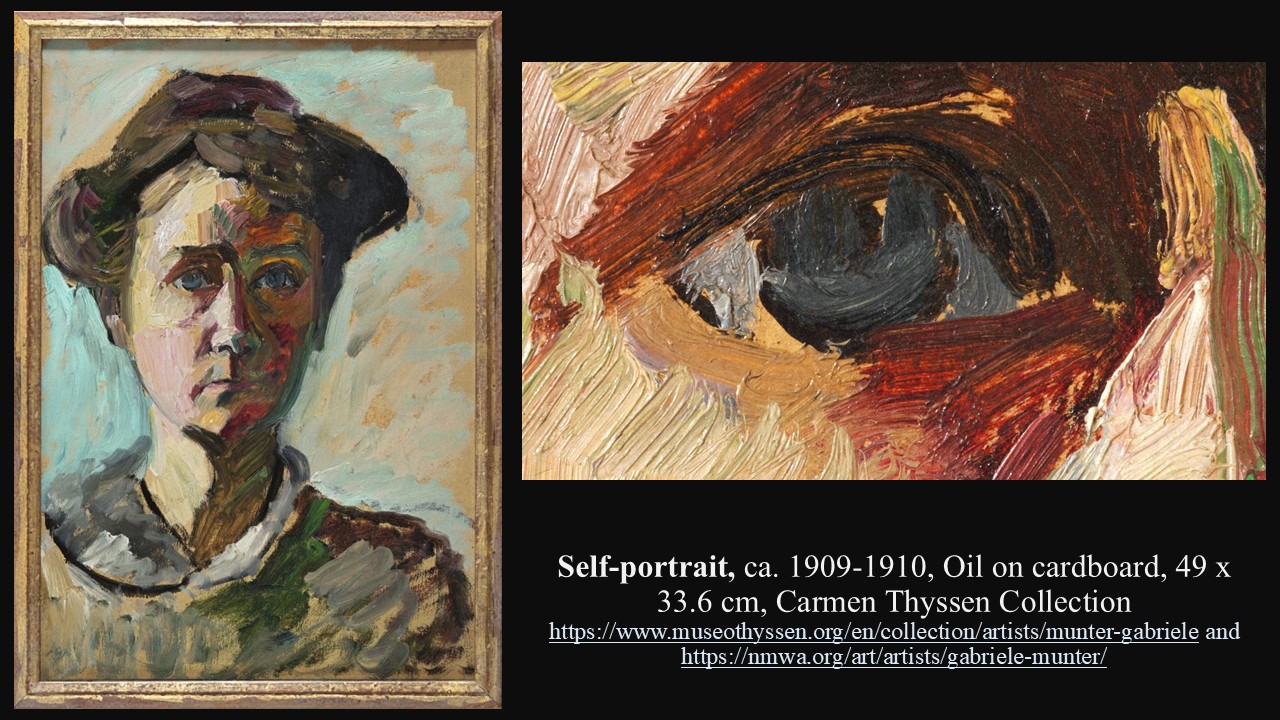

Self-Portrait in front of an easel, ca. 1908–09, Oil on Canvas, 78 × 60.5 cm, Princeton University Art Museum, NJ, USA https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/33606

Gabriele Münter, a key figure in early 20th-century expressionism, once remarked, “I depicted the world the way it essentially appeared to me, how it took hold of me…” This sentiment underscores her ability to channel raw emotion and a deeply personal perspective into her vivid landscapes and striking portraits. Her work, celebrated for its bold use of colour and emotive simplicity, was on display at the Museo Thyssen in Madrid, offering visitors a chance to explore the artistic legacy of a woman who helped shape modern art. As we celebrate April 15 Arts Day—a tribute to creativity’s power to inspire and transform—Münter’s work reminds us of the importance of viewing the world through an authentic, unfiltered lens. https://www.museothyssen.org/en/exhibitions/gabriele-munter and https://www.unesco.org/en/days/world-art

Münter was a German painter and a key figure in early 20th-century Expressionism. Born in Berlin, she displayed an early interest in art and studied at the progressive Phalanx School in Munich, where she met Wassily Kandinsky, with whom she had a long romantic and artistic partnership. Münter was a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), an influential artistic movement that sought to break from traditional academic painting and embrace spiritual and emotional expression through colour and form. During her career, she traveled extensively, experimenting with different artistic styles before settling in Murnau, where her art flourished. Despite facing challenges as a female artist and the disruptions of war, she played a crucial role in preserving many of Der Blaue Reiter’s artworks, which she hid from the Nazis during World War II.

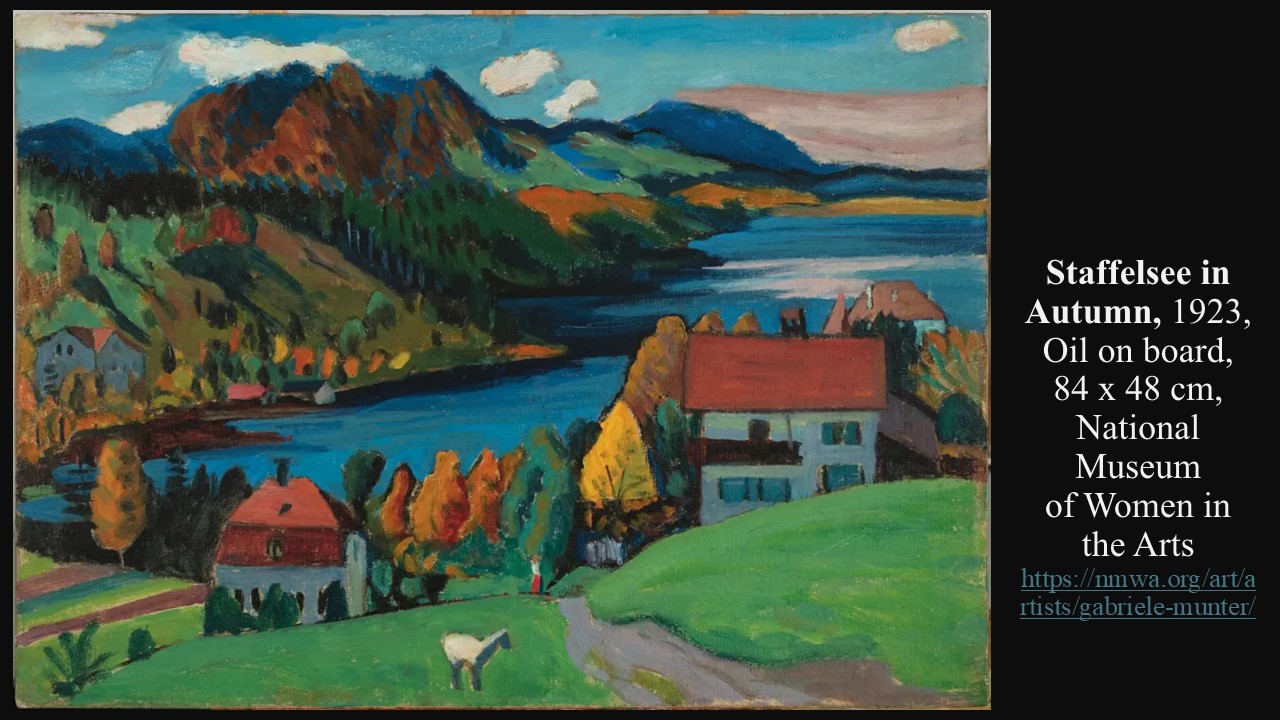

Her work is characterized by bold colours, simplified forms, and an emphasis on emotional intensity, aligning her with German Expressionism. While often overshadowed by Kandinsky, her paintings demonstrate a distinct style that merges folk art influences with modernist sensibilities. Her landscapes, such as Autumn in Murnau (1908), feature dynamic compositions and a vibrant palette that convey both structure and spontaneity. She also produced striking portraits that emphasize psychological depth, often using strong outlines and flattened perspectives. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Münter retained a representational quality in her work, balancing abstraction with figuration. Over time, her contributions to modern art have gained greater recognition, securing her place as a pioneering force in early 20th-century avant-garde movements.

Gabriele Münter’s Self-Portrait in the Princeton University Art Museum presents a striking image of the artist as both a determined professional and a woman navigating the challenges of the early 20th-century art world. Seated before her easel, she wears a wide-brimmed straw hat—a symbol of her plein-air landscape painting practice—while her intense gaze meets the viewer with quiet confidence. Though still young, her expression conveys resilience and self-assurance, reflecting the perseverance required to establish herself in a male-dominated field. The composition aligns Münter with the great tradition of artists from Rembrandt to Van Gogh, who often depicted themselves at work, reinforcing her identity as a serious painter. Created upon her return to Munich with Kandinsky after years of travel, the portrait also marks her role in shaping modernism as a founding member of the New Artists Association Munich. With its bold yet controlled brushwork and emphasis on psychological depth, this self-portrait asserts Münter’s place within the avant-garde while simultaneously challenging traditional expectations of female artists.

From November 12, 2024, to February 9, 2025, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid hosted “Gabriele Münter: The Great Expressionist Woman Painter,” the first retrospective of the German artist in Spain. The exhibition featured over 100 works, including paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs, showcasing Münter’s evolution as a pioneering figure in early 20th-century German Expressionism. It began with her early work as an amateur photographer, highlighting how this modern medium influenced her artistic development. The exhibition then explored her paintings created during travels across Europe and North Africa with her partner, Wassily Kandinsky, and included masterpieces from the Blue Rider period. The final section focused on her exile in Scandinavia during World War I and her subsequent artistic explorations upon returning to Germany. This comprehensive exhibition aimed to shed light on an artist who defied the limitations imposed on women of her time, solidifying her status as a central figure in German Expressionism.

For a PowerPoint Presentation on Gabriele Münter’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/story/works-gabriele-m%C3%BCnter