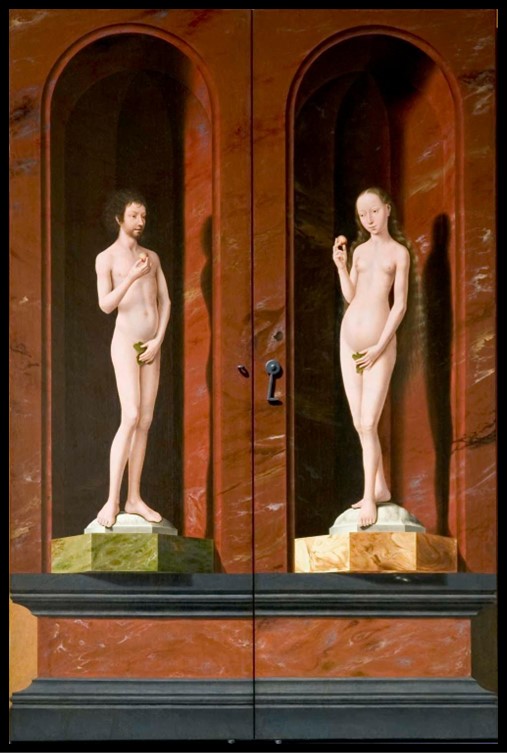

Panoramic view of the frescoes, 1320-40, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Σήμερον κρεμᾶται ἐπὶ ξύλου ὁ ἐν ὕδασι τὴν γῆν κρεμάσας. Στέφανον ἐξ ἀκανθῶν περιτίθεται ὁ τῶν Ἀγγέλων Βασιλεύς. Ψευδῆ πορφύραν περιβάλλεται ὁ περιβάλλων τὸν οὐρανὸν ἐν νεφέλαις. Ῥάπισμα κατεδέξατο ὁ ἐν Ἰορδάνῃ ἐλευθερώσας τὸν Ἀδάμ. Ἥλοις προσηλώθη ὁ Νυμφίος τῆς Ἐκκλησίας. Λόγχῃ ἐκεντήθη ὁ Υἱὸς τῆς Παρθένου. Προσκυνοῦμέν σου τὰ Πάθη, Χριστέ. Δεῖξον ἡμῖν καὶ τὴν ἔνδοξόν σου Ἀνάστασιν/ (Good Friday – Μεγάλη Παρασκευή) Ἀντίφωνον ΙΒ΄ – ἦχος πλ. δ΄) http://www.hchc.edu/assets/files/CD/All_Creation_Trembled_ebook.pdf

Today he who hung the earth upon the waters is hung upon a Tree. He who is King of the Angels is arrayed in a crown of thorns. He who wraps the heaven in clouds is wrapped in mocking purple. He who freed Adam in the Jordan receives a blow on the face. The Bridegroom of the Church is transfixed with nails. The Son of the Virgin is pierced by a lance. We worship your Sufferings, O Christ. Show us also your glorious Resurrection. (Good Friday – Μεγάλη Παρασκευή Twelfth Antiphon – plagal fourth mode) http://www.hchc.edu/assets/files/CD/All_Creation_Trembled_ebook.pdf

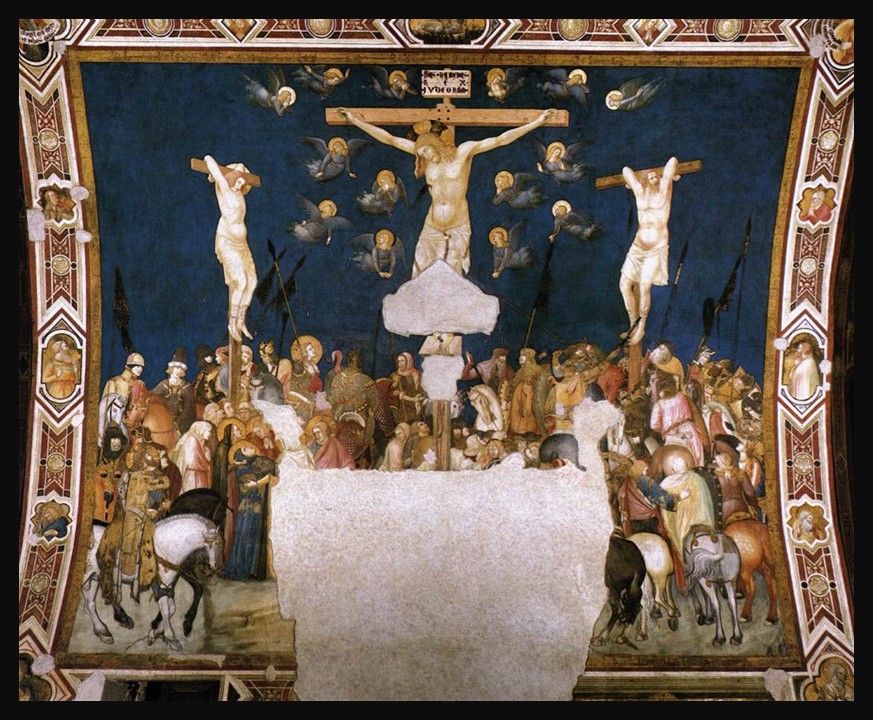

Nestled within the hallowed walls of the Lower Church of San Francesco in Assisi, Pietro Lorenzetti’s Crucifixion fresco stands as a haunting yet masterful portrayal of sorrow, sacrifice, and divine transcendence. Painted in the early 14th century, this monumental work is a cornerstone of Lorenzetti’s artistic legacy, embodying the emotional intensity and narrative depth that defined Sienese painting. As part of the broader cycle of frescoes adorning the basilica, the Crucifixion transforms the left transept into a space of profound contemplation, where art and faith converge in striking realism and dramatic composition. In this post, we will explore the fresco’s artistic significance, its place within the basilica’s iconographic program, and the deeply human expressions that set Lorenzetti’s vision apart from his contemporaries.

Panoramic view of the frescoes, 1320-40, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy https://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/l/lorenzet/pietro/index.html

The Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi is one of the most revered pilgrimage sites in Italy, built to honor Saint Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan Order. Constructed shortly after his canonization in 1228, the basilica is a masterpiece of medieval architecture, blending Romanesque solidity with the soaring elegance of early Gothic design. It consists of two distinct churches, the Upper Church, with its luminous frescoes by Giotto and Cimabue, and the Lower Church, a more intimate, shadowed space adorned with the works of Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini. Beneath these sacred walls lies the Crypt of Saint Francis, drawing countless visitors who seek spiritual reflection and artistic inspiration. Beyond its role as a religious site, the basilica is a testament to the power of art in shaping faith, as its fresco cycles revolutionized narrative painting in the 13th and 14th centuries, setting a precedent for Renaissance masters to come.

Stepping into the Lower Church of San Francesco is like entering a sanctuary of shadow and splendor, where the interplay of dim light and rich color creates an atmosphere of deep reverence. In contrast to the soaring luminosity of the Upper Church, the Lower Church is a more intimate and solemn space, its vaulted ceilings and walls covered in some of the most exquisite fresco cycles of the 13th and 14th centuries. The Sienese masters Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini, along with other painters, adorned the chapels and transepts with emotionally charged narratives from the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary, employing striking realism, dramatic gestures, and a masterful use of color. Lorenzetti’s Crucifixion and Deposition stand out for their raw human expression, while Martini’s elegant, courtly style infuses his frescoes with a lyrical grace. Gold accents, deep blues, and rich ochres further heighten the mystical aura, turning the church into a profound visual meditation on faith, sacrifice, and redemption.

Panoramic view of the frescoes, 1320-40, Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Pietro Lorenzetti’s Crucifixion in the Left Transept of the Lower Church of San Francesco is a profoundly dramatic and emotionally charged depiction of Christ’s suffering. Painted in the early 14th century, the fresco exemplifies Lorenzetti’s mastery of naturalism, spatial depth, and psychological intensity, setting it apart from the more hieratic Byzantine traditions. The composition is filled with raw human emotion. The anguished expressions of the gathered crowd, including Roman soldiers and sorrowful onlookers, heighten the sense of immediacy and realism. Lorenzetti employs bold foreshortening, dynamic gestures, and chiaroscuro effects to create depth and a sense of movement, drawing the viewer into the heart of the scene. The somber colour palette, dominated by earthy reds, deep blues, and stark contrasts, reinforces the tragic weight of the moment. As part of the broader fresco cycle in the transept, this Crucifixion not only serves as a meditation on Christ’s sacrifice but also marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of Sienese painting, bridging the gap between Gothic spirituality and the emerging naturalism that would shape the Renaissance.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Pietro Lorenzetti’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.keytoumbria.com/Assisi/S_Francesco_LC_Transepts.html and https://www.visit-assisi.it/en/monuments/religious-buildings/papal-basilica-of-saint-francis-and-the-sacred-convent/