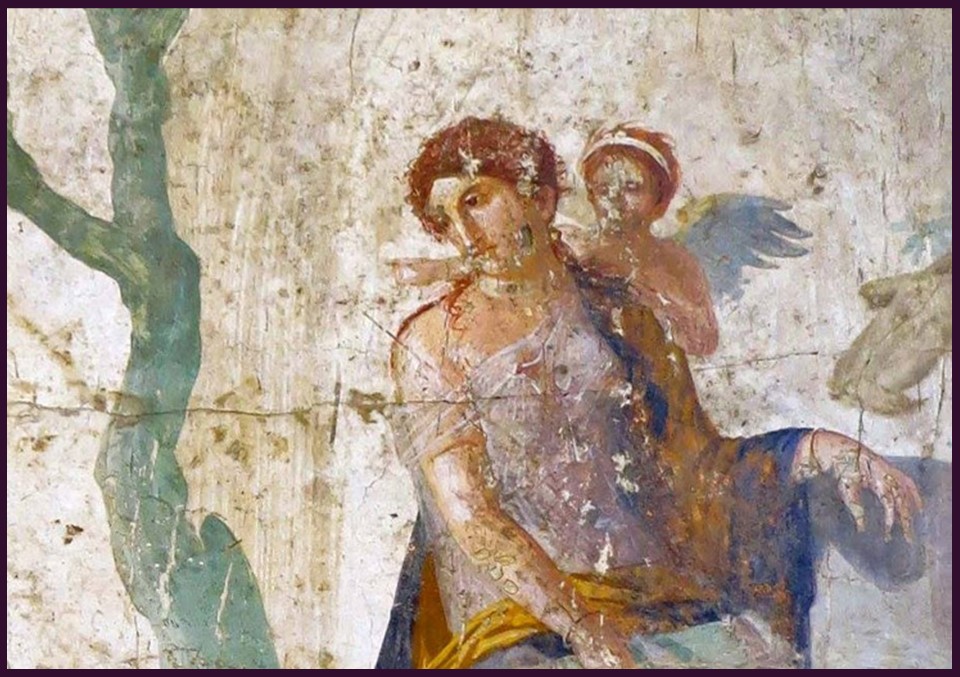

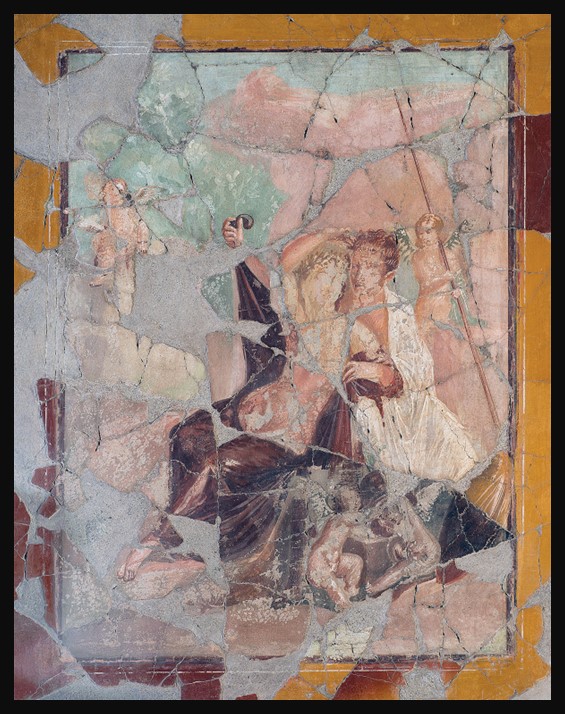

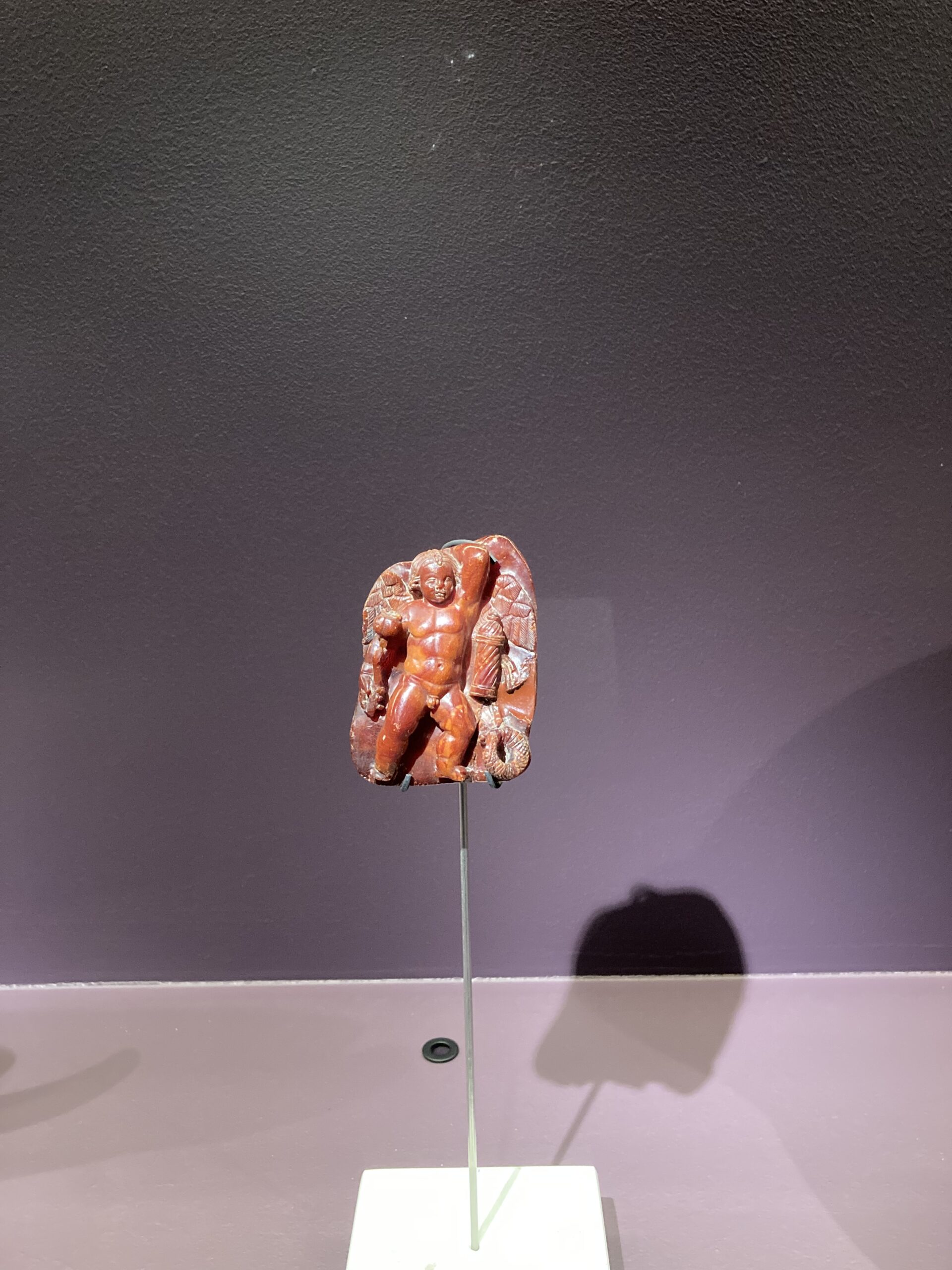

Unfortunately / for me / Eros never rests / but like a Thracian tempest / ablaze with lightning / emanates from Aphrodite; / the results are frightening― / black, / bleak, / astonishing, / violently jolting me from my soles / to my soul… writes the unknown 6th century BC ancient Greek poet in ‘Ibykos Fragment 286’. In Plaque with Eros as a Sleeping Child, the enchanting small carving from Trieste, the unruly God of Love… is resting!

The Museo d’Antichità ‘J. J. Winckelmann’ in Trieste, Italy, is a distinguished institution dedicated to preserving and exhibiting ancient artifacts. Named after the renowned German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, often considered the father of modern archaeology and art history, the museum boasts an impressive collection of antiquities. These include Greek, Roman, and Etruscan artefacts, reflecting the rich historical tapestry of the region. The museum is not only a treasure trove of classical art but also a center for scholarly research, offering insights into the ancient civilizations that shaped the Mediterranean world. Its exhibits provide visitors with a profound understanding of historical continuity and cultural heritage, making it a pivotal cultural landmark in Trieste.

The Archaeological Museum in Trieste houses a remarkable collection of Roman antiquities crafted from Amber, showcasing the material’s significance and allure in ancient times. Amber, a term referring to various fossil resins that range in colour from yellow to orange, red to brown, and exhibit varying degrees of transparency, has been prized and crafted since prehistoric times. Admired for its qualities and believed to possess protective properties, Amber was extensively used by the Romans for decorative and ceremonial objects.

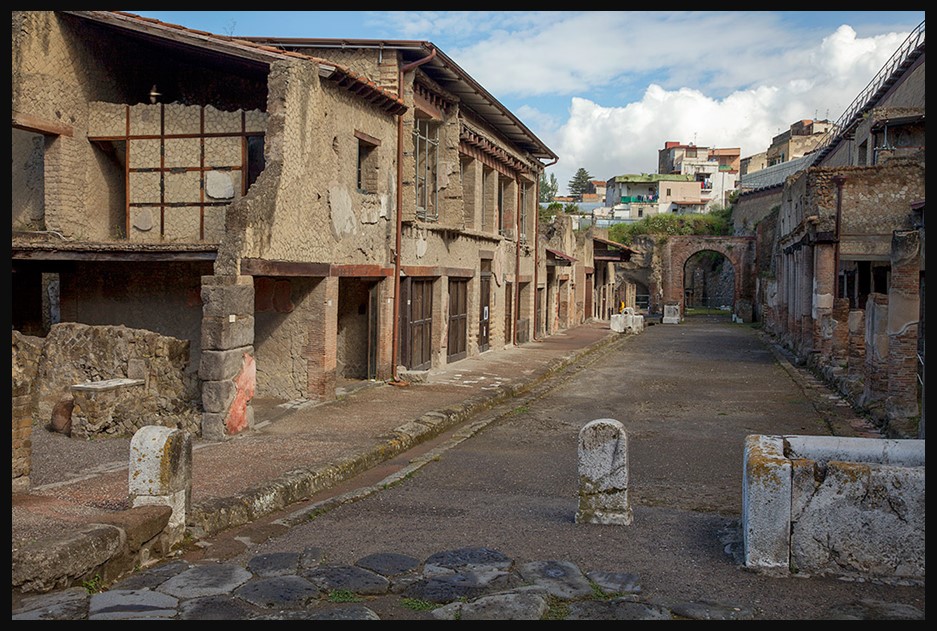

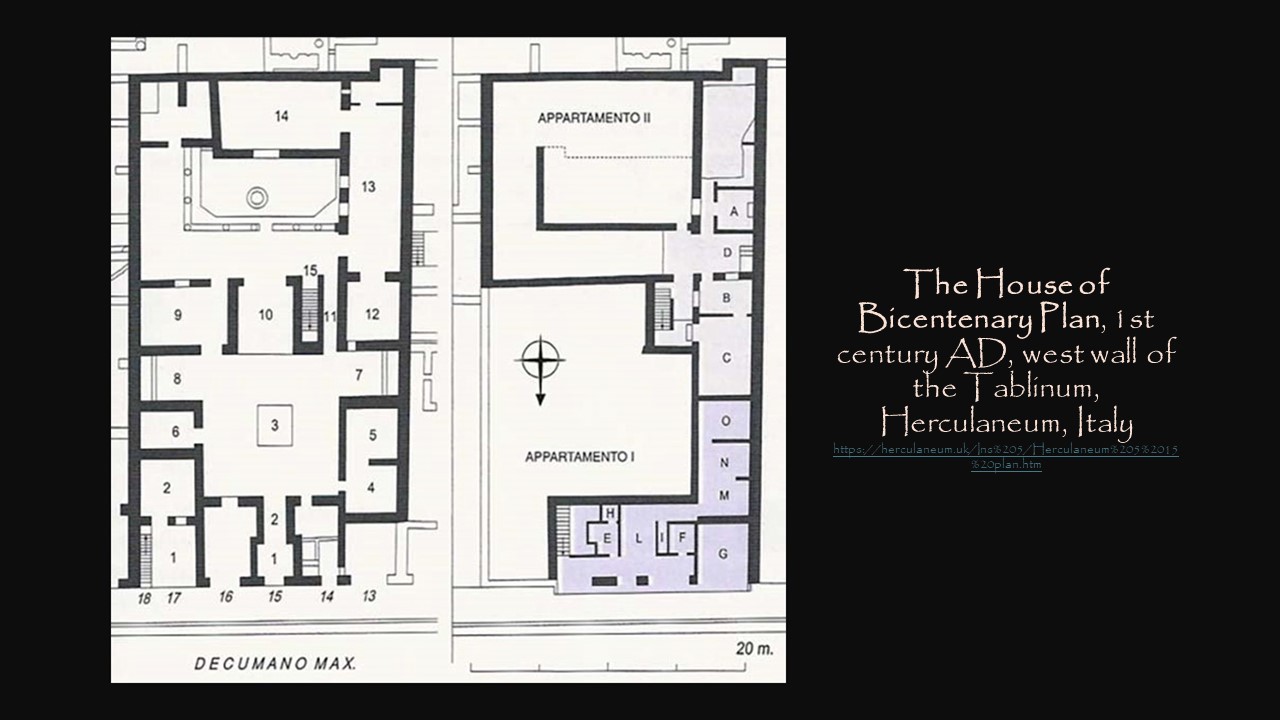

Collected primarily along the coasts of the Baltic Sea, Amber made its significant appearance in the Roman world around the mid-1st century AD. This timing coincides with the pacification of the Empire’s Danube border, suggesting that Germanic peoples likely traded Amber from this region. The precious resin reached Italy via the ‘Amber Route,’ an intricate network of transalpine paths linking the eastern Adriatic to the Danube. Aquileia considered the terminal of this route, saw the rise of a vibrant Amber carving industry renowned for its intricate and refined designs, some inspired by Egyptian motifs.

The ‘J. J. Winckelmann’s Museum showcases exquisite amber artefacts from Aquileia, dating from the mid-1st to the 2nd century AD. Its collection includes intricately carved jewelry, amulets, and small statuettes, reflecting the high level of craftsmanship and artistic expression of the period. These pieces offer a glimpse into the luxury and sophistication of Roman society, illustrating how amber was not only a symbol of wealth and status but also played a role in daily life and spiritual practices. This fine collection at the Museo d’Antichità provides invaluable insights into the cultural and historical context of amber in the ancient world, making it a highlight for visitors and scholars alike.

Among the finest Roman Amber artefacts in the Museo d’Antichità ‘J. J. Winckelmann’ in Trieste, is the Plaque with Eros as a Sleeping Child and a Poppy Capsule, symbol of sleep. This exquisite small artefact, dating from the mid-1st to the 2nd century AD, showcases the exceptional craftsmanship of ancient Roman artisans. The serene image of the slumbering Eros, with delicate features and a peaceful expression, embodies the intricate artistic expression and symbolic richness of the period. The poppy capsule held by Eros underscores the connection to sleep and dreams, offering a poignant glimpse into Roman mythology and the cultural significance of Amber. This plaque not only highlights the luxurious use of Amber in art but also provides profound insight into the spiritual and daily life of Roman society, making it a treasured piece within the museum’s collection.

For a Student Activity, inspired by the Amber Plaque with Eros as a Sleeping Child, please… Check HERE!

On February 17, 2024, during my visit to Athens, Greece, I had the pleasure of attending the exceptional exhibition titled ‘NοΗΜΑΤΑ’: Personifications and Allegories from Antiquity to Today, held at the Acropolis Museum. Curated by Professor Nikolaos Chr. Stampolidis and his associates, this exhibition formed a unique Tetralogy, wherein the Greek word ‘ΝΟΗΜΑ’ (‘Meaning’ in English) metaphorically transformed into ‘ΝΗΜΑ’ (‘Thread’), weaving together diverse artworks including statues, reliefs, vases, coins, jewelry, Byzantine icons, and paintings. Among the Exhibition artworks that impressed me most was Plaque with Eros as a Sleeping Child, a small Amber carving from the Museo d’ Antiquita, ‘J. J. Winckelmann’ in Trieste, Italy!