Nestled within the Musei Capitolini in Rome, the charming marble statue of Eros and Psyche captures a tender moment of love and longing from ancient mythology. About a year ago, on February 17, 2024, while attending ΝοΗΜΑΤΑ: Personifications and Allegories from Antiquity to Today, an exceptional exhibition at the Acropolis Museum in Athens, I came face to face with this adorable work of art. I was enchanted, as it beautifully portrays the intimate bond between the god of love and the mortal maiden, offering visitors a glimpse into the artistry and emotion of classical antiquity.

When I ask questions, starting with ‘who,’ ‘how,’ ‘where,’ ‘why,’ and ‘what,’ about the statue of Eros and Psyche in Rome, I find myself uncovering its historical context, artistic significance, and the captivating story behind its creation. Let’s do it!

Who are ‘Eros and Psyche’ in classical mythology, and How do their roles and stories shape the meaning and emotional resonance of the statue? Eros (Cupid in Roman mythology) is the god of love and desire, often depicted as a youthful figure with wings, symbolizing the fleeting and unpredictable nature of love. Psyche, whose name means “soul” in Greek, is a mortal woman of extraordinary beauty. Their story, immortalized in Apuleius’ The Golden Ass (also known as Metamorphoses), narrates the trials and ultimate union of love (Eros) and the soul (Psyche), symbolizing the transformative power of love and its ability to overcome challenges.

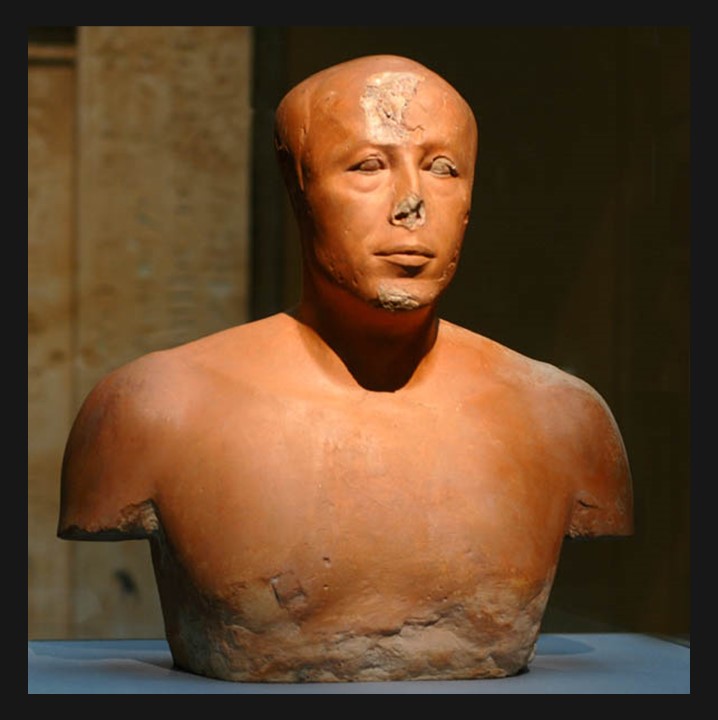

Who was the sculptor of ‘Eros and Psyche’ in the Musei Capitolini? The sculptor of the ‘Eros and Psyche’ statue in the Musei Capitolini is unknown. This marble work is a Roman copy (1st or 2nd century AD) of a Hellenistic original, typical of the 2nd century BC. Roman sculptors frequently replicated Greek masterpieces, adapting them to suit Roman tastes while preserving the essence of the original composition. The anonymity of the artist adds an air of mystery to the statue, leaving its artistry to speak for itself.

How does the statue of ‘Eros and Psyche’ convey the universal themes of love, perseverance, and redemption through its composition and emotional resonance? In the statue, their tender embrace embodies the culmination of their myth: the union of love and soul after overcoming trials. This intimate moment resonates emotionally, as it speaks to universal themes of love, perseverance, and redemption. The depiction elevates their myth from a simple narrative to an allegory of human experience, giving the statue profound meaning and aesthetic significance.

What techniques did the artist employ to achieve the statue’s graceful balance and sentimental appearance? The artist of the ‘Eros and Psyche’ statue employed classical techniques to achieve its graceful balance and sentimental appearance. The use of a contrapposto stance gives the figures a dynamic yet harmonious pose, while the smooth textures and finely carved drapery add a sensual softness that enhances their tender connection. Subtle facial expressions and intertwined gestures evoke emotional depth, while meticulous attention to proportion and symmetry underscores their unity as counterparts—love and soul. The dynamic composition, with its circular flow, draws the viewer’s eye and reinforces the theme of eternal unity, making the statue both aesthetically captivating and emotionally resonant.

How does the Roman statue of ‘Eros and Psyche’ reflect the artistic trends or cultural values of its time? The statue reflects the artistic trends and cultural values of its time by embodying the Roman fascination with Greek mythology and the idealized human form. Created during the Roman Imperial period, it demonstrates the Roman practice of replicating and adapting Hellenistic art, emphasizing naturalism, emotional expression, and harmonious proportions. The statue’s tender depiction of love and the soul aligns with the Roman cultural appreciation for storytelling, allegory, and themes of morality and virtue. Additionally, it reflects the Roman value placed on intimate and domestic scenes, which were often used to adorn villas and gardens, symbolizing love, beauty, and emotional depth in everyday life.

Where was the statue discovered, and what does its provenance reveal about its historical journey before becoming part of the Capitoline collection? The Eros and Psyche statue was discovered on the Aventine Hill in Rome during the 18th century, in the garden of the vigna of Panicale in February 1749, to be specific. Its provenance highlights its origins as a Roman Imperial copy of a Hellenistic Greek original, crafted to adorn an elite Roman residence or garden. The discovery on the Aventine Hill, an area historically associated with wealthy Roman villas, suggests the statue was a decorative piece intended to evoke classical ideals of love and beauty in a private, refined setting. Its acquisition by the Capitoline Museums, through a Pope Benedict XIV donation shortly after the statue’s discovery, underscores the Enlightenment-era fascination with antiquity and the desire to preserve and showcase classical art as a cultural and historical treasure.

Why has this statue inspired numerous artists to create their own interpretations of the Cupid and Psyche myth? The Eros and Psyche statue has inspired numerous artists, including Antonio Canova, because it captures the timeless themes of love, desire, and the union of the human soul with divine affection. Its tender composition and emotional resonance offer a perfect balance of aesthetic beauty and narrative depth, making it an ideal subject for reinterpretation. For artists like Canova, who sought to revive classical ideals during the Neoclassical period, the statue’s portrayal of mythological characters in a moment of intimacy provided a rich source of inspiration to explore human emotions and the universal power of love through their own artistic lens.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of the Eros and Psyche theme, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupid_and_Psyche_(Capitoline_Museums) and https://www.museicapitolini.org/en/opera/statua-di-amore-e-psiche and https://human.libretexts.org/Courses/Saint_Mary’s_College_(Notre_Dame_IN)/Humanistic_Studies/HUST_292%3A_Reclaiming_the_Classical_Past_for_a_Diverse_and_Global_World/01%3A_Apuleius-_Cupid_and_Psyche