The Etruscans, a powerful and enigmatic civilization of central Italy, played a vital role in shaping the cultural foundations later adopted by the Romans. Renowned for their elaborate funerary customs, they believed in providing for the dead in ways that reflected both status and the joys of earthly life, leading to the creation of richly decorated tombs that serve as lasting testaments to their artistry and worldview. The Necropoli dei Monterozzi near Tarquinia exemplifies this tradition, as one of the most important burial grounds of the ancient Mediterranean, where hundreds of painted chambers offer a vivid glimpse into Etruscan society. Among these, the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, dating to around 520–510 BC, stands out for its lively frescoes that celebrate nature, leisure, and the afterlife, making it a masterpiece of Etruscan funerary art.

The Necropoli of Monterozzi holds immense archaeological significance as it preserves the largest collection of painted Etruscan tombs, offering unparalleled insight into the beliefs, daily life, and artistic achievements of this ancient culture. Discovered in the early nineteenth century, the site quickly became a focal point for antiquarian interest, with early excavations often driven more by the desire to uncover treasures than by scientific methods. Over time, however, more systematic archaeological approaches have revealed the necropolis’ historical depth, documenting over 6,000 tombs ranging from simple chamber burials to elaborately decorated family vaults. The frescoes, in particular, have transformed scholarly understanding of Etruscan society, as they preserve vibrant scenes of banquets, rituals, and natural landscapes that rarely survive in other contexts, making Monterozzi a cornerstone in the study of pre-Roman Italy.

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, discovered in 1873 during a period of intensive investigation at the Necropoli of Monterozzi, represents one of the most significant finds of late nineteenth-century Etruscan archaeology. Documentation from the time, however, provides only fragmentary information regarding the circumstances of its excavation, the personnel involved, and the precise condition of the monument upon opening. Despite these gaps, contemporary commentators consistently remarked upon the striking preservation of the painted decoration, noting with particular interest the unprecedented imagery of fishermen, hunters, and divers that expanded the known repertoire of Etruscan funerary art. Although anecdotal testimony concerning local responses or early interventions is scarce, the tomb rapidly entered scholarly discourse and has since been recognized as an essential source for understanding the interplay of ritual, daily life, and conceptions of the afterlife in Etruscan culture.

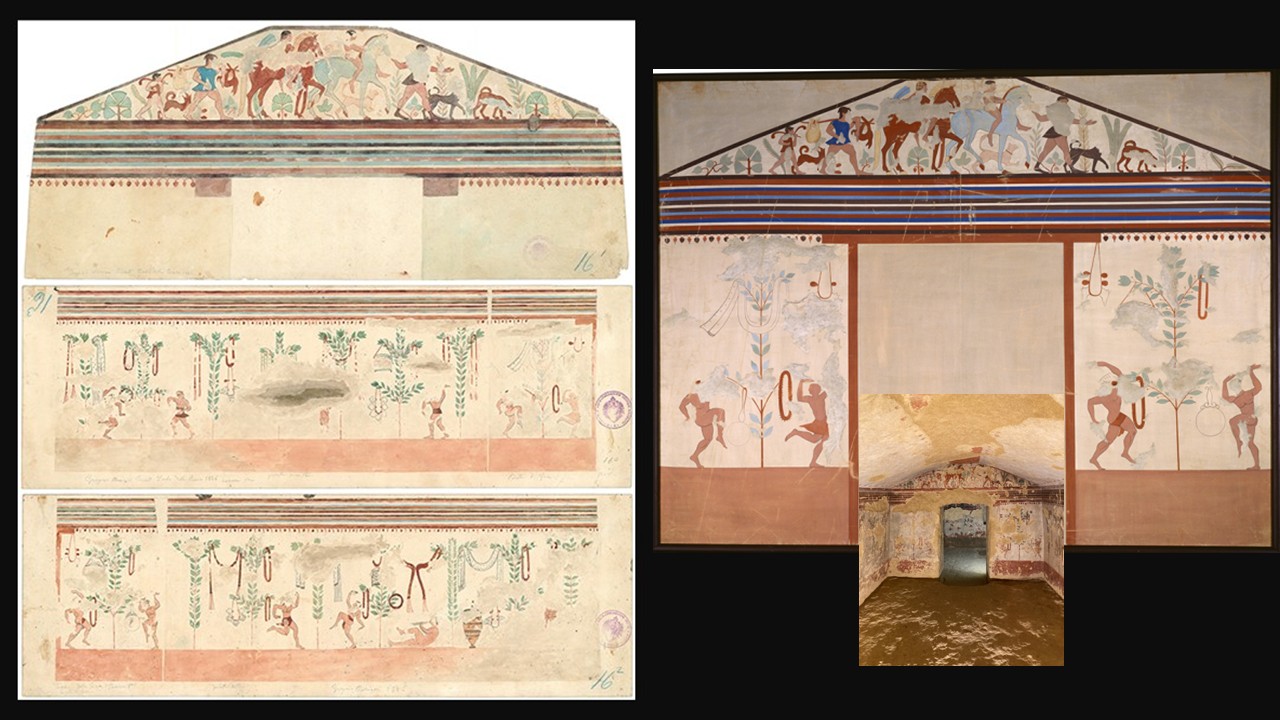

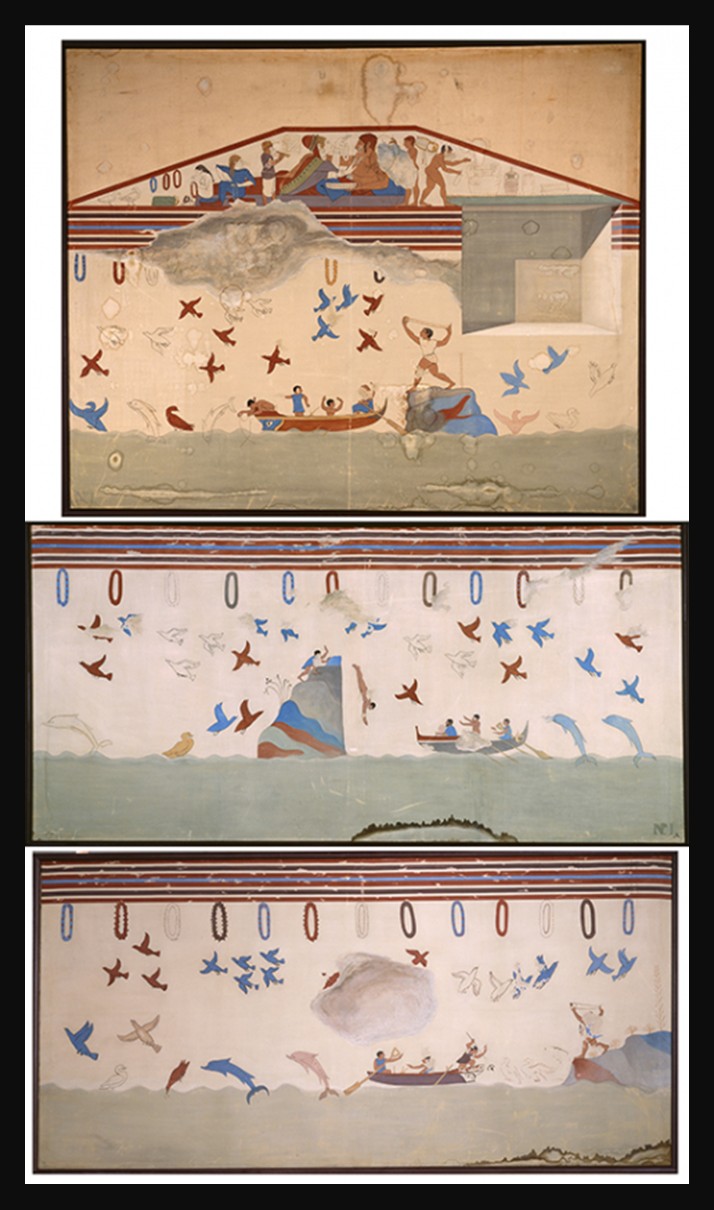

Crucial to the legacy of the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing are the watercolours produced by the artist Gregorio Mariani soon after its discovery. His meticulous reproductions, later published in chromolithograph form, captured the vibrant hues and delicate details of the frescoes at a moment when they were far fresher than today. These images not only provided scholars with reliable records of motifs that have since deteriorated, but also played a vital role in popularizing the tomb’s significance within the wider field of Etruscan studies. Original Mariani watercolours are preserved in the archives of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, while facsimile reproductions can be found in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. In this way, Mariani’s work serves as both an artistic achievement and a scientific tool, bridging the gap between nineteenth-century discovery and modern scholarship.

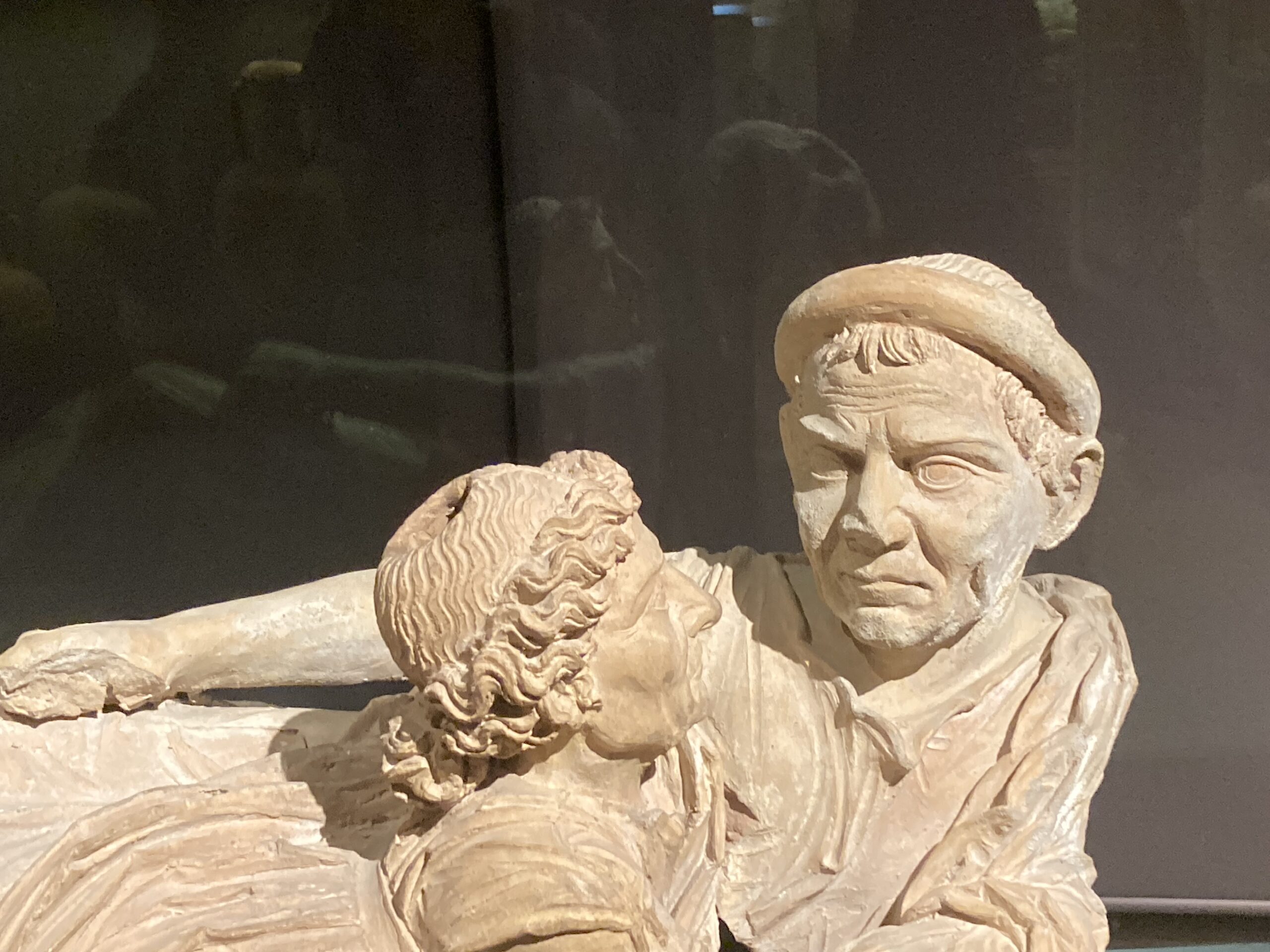

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing is a two-chambered burial space whose walls are adorned with some of the most dynamic and evocative frescoes in Etruscan art. The imagery vividly depicts scenes of everyday leisure and subsistence: Dionysian figures dancing in a sacred grove, hunters chasing game, fishermen casting nets, youths diving into clear waters, and birds in flight above lush landscapes.

Etruscan Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, 520-510 BC,Necropoli dei Monterozzi, near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

In the antechamber, the frescoes depict nearly naked figures engaged in what appears to be a Dionysian ritual dance, set within a grove adorned with ribbons, wreaths, mirrors, and cistae. Reclining satyrs holding rhytoi occupy the gable of the entry wall, underscoring the influence of the cult of Dionysus on Etruscan religion and funerary practices. On the back wall, a hunting scene unfolds, with hunters and dogs returning with their quarry through a lush, almost tropical landscape filled with vibrant vegetation. This juxtaposition of ritual and daily activity illustrates both spiritual and worldly dimensions, highlighting the Etruscans’ belief in the continuation of life’s pleasures beyond death.

In the main burial chamber, the frescoes shift focus from activity to celebration, illustrating scenes that suggest both ritual and leisure. Youths are depicted diving and swimming in carefully delineated waters, while birds and aquatic creatures populate the surrounding environment, emphasizing a harmonious interaction between humans and nature. The figures are arranged in continuous sequences that convey narrative flow, as if time itself is unfolding across the walls. Here, the painter employs brighter pigments and more elaborate detailing, particularly in the depiction of musculature, drapery, and facial expressions, giving the scenes a remarkable sense of immediacy and life. Together, the two chambers combine to create a vision of an idealized Etruscan existence, where work, sport, and the pleasures of the natural world coexist with an underlying sense of spiritual continuity.

The composition is notable for its sense of movement and rhythm, as figures and animals are arranged in continuous, flowing sequences that suggest both narrative and ritual significance. Bright ochres, reds, and blues bring the scenes to life, while careful attention to proportion and perspective conveys depth and realism unusual for the period. Beyond their aesthetic appeal, the frescoes offer a profound insight into Etruscan conceptions of the afterlife, suggesting a vision in which the pleasures and activities of earthly existence continue beyond death, making the tomb not only a funerary monument but also a celebration of life itself.

For a Student Activity inspired by the frescoes in the Antechamber of the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: Abundance of Life: Etruscan Wall Painting, by Stephan Steingräber https://books.google.gr/books?id=K25ydBTGhbkC&pg=PA95&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false and Anni 1880: Tomba della Caccia e Pesca e Tomba degli Auguri https://journals.openedition.org/mefra/8455